The Barons of Broadway #28

In this episode of Barons of Broadway, we explore the origins and early history of Lochbourne. This hidden jewel, listed on the National Register of Historic Places, is located at 406 North Broadway in Upper Nyack. Known historically as Lochbourne, its stone foundation suggests roots that predate the Civil War. Behind the historic charm of this three-story Victorian mansion lies a remarkable list of owners and residents, each adding a unique layer to the estate’s storied past. Oral histories passed down through its owners recount the estate’s potential role in the Underground Railroad and the possibility of a forgotten Black cemetery predating emancipation.

Notable past inhabitants include a pre-Civil War doctor, a financier who supported the Union’s war efforts, a Scottish grain merchant turned socialite, and Winston Churchill—a best-selling American author. The estate also housed a scientist whose research contributed to our understanding of cellular biology, an attorney involved in the Alger Hiss case of the 1950s, and most recently, Izzy Cohen, a 58-year resident and an early advocate of the work from home movement.

Lochbourne hides behind a contemporary home and a screen of lush trees, becoming most visible during the winter months. Its historic carriage house, one of Nyack’s finest, offers scenic views of Upper Nyack Brook as it winds along Old Mountain Road.

Estate Name

An 1891 map labels the estate “Brookside,” a rough Anglicized translation of Lochbourne. The word “Lochbourne” appears inscribed on a door sill leading to the basement, and an alternate spelling, “Lochburn,” surfaces in a 1945 Journal News article. The Scottish name likely emerged in the late 19th century when Gilded Age estates often adopted such motifs. Across the street, Glenholme (renovated in 1895) and nearby Glen Iris (built in 1900) reflect this tradition. The baronial style conveyed wealth and sophistication, appealing to the nouveau riche of the era.

The name “Lochbourne” combines the Scottish words loch (bay) and bourne (small stream). The estate’s location beside Upper Nyack Brook, with views of the Tappan Zee, fits this name perfectly. The brook carves a deep gulley near the property, and a small dam along Broadway creates a pond. Across Old Mountain Road from the carriage house lies the Old Palmer Burial Grounds, an area steeped in history. Early settlers likely followed Old Mountain Road, which may trace a path originally used by indigenous people.

Indigenous People

Izzy Cohen, the current owner, has uncovered 30–40 broken arrowheads and stone tools near the estate’s porte cochere, along with nearby oyster shells—likely remnants of an ancient midden. These findings suggest that indigenous people used the seasonal path that later became Old Mountain Road. They may have also used a shortcut across the property between Old Mountain Road and North Broadway. Unfortunately, little else is known about the area’s indigenous habitation.

Early Colonial Owners

The property’s early ownership traces back to the Knapp family, who purchased a large farm in 1762. They likely lived in a Dutch stone house along North Broadway, south of Lochbourne.

In 1787, Henry Palmer, who had married into the Knapp family, acquired the farm after fleeing British incursions during the Revolutionary War. Henry and his son, James Palmer, lived in nearby homes near the Old Stone Meeting House. James supported the creation of a Methodist church, today known as the Old Stone Meeting House, and deeded land for the Old Palmer Burial Grounds. Cornelius Kuyper, Upper Nyack’s original settler and landowner, was buried there in 1739.

A Forgotten Black Cemetery

The 1800 census records enslaved individuals on three of six farms in Upper Nyack. Enslaved people were unlikely to be buried in the Old Palmer Burial Grounds alongside white settlers. Historian Frank Green describes a Black cemetery located south of Old Mountain Road and west of Upper Nyack’s first school. Izzy Cohen notes that a row of carefully arranged, irregular, unmarked sandstones behind the house suggests possible early gravesites. Although no other physical evidence of an early Black cemetery remains, Green’s description places it on what later became Lochbourne’s property.

These stones in Lochbourne’s backyard appear to be unmarked tombstones arranged for a purpose. The stones existed in this spot for the last 60 years.

Dr. James Allen and Early Construction

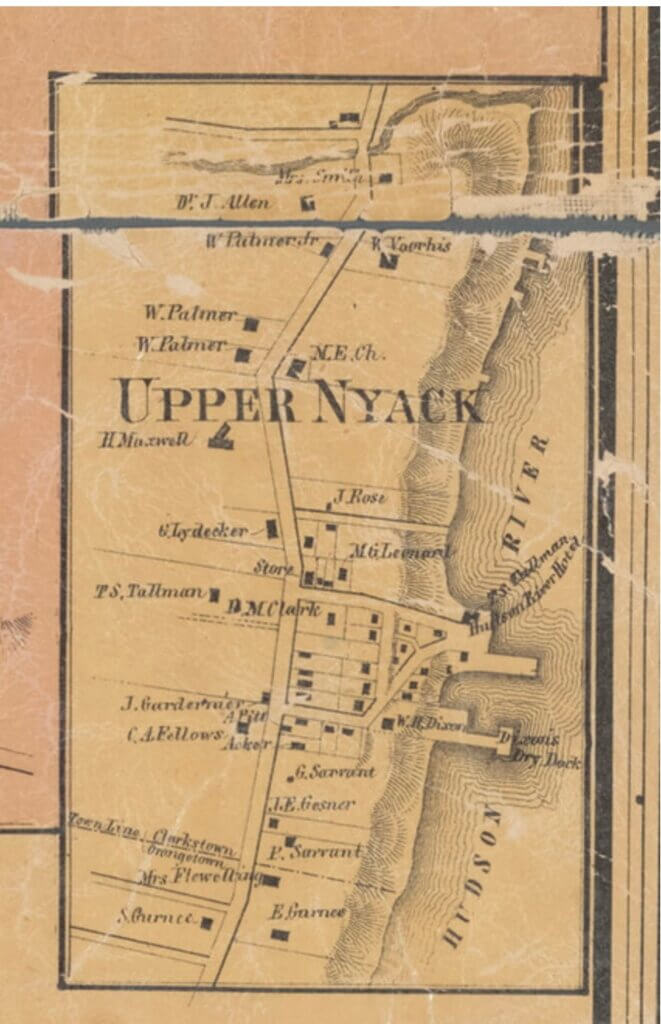

By the mid-1850s, Dr. James Allen owned the property, as evidenced by maps from that era. He promoted the sale of “40 acres of choice fruit land overlooking the Hudson River.” Upper Nyack’s hillsides, renowned for producing apples, peaches, and grapes, enticed potential buyers.

Remnants of foundations suggest the presence of a small dwelling predating Allen’s ownership. These brick and brick-and-stone foundations indicate that multiple structures once occupied the site. A brick foundation, now concealed behind a curving stone veranda, features windows with hand-forged metal frames in the basement. This modest structure, whether constructed by Allen or a prior owner, may have served as the site’s original home.

Underground Railroad Station?

The specifics of Nyack’s role in the Underground Railroad remain elusive. Historians generally credit Cynthia Hesdra as the local conductor, but no documented evidence reveals where runaway slaves were hidden. Lochbourne, however, stands out as a potential site due to its unique architectural features and lingering rumors.

In The History of Rockland County, Frank Green recounts a story told by his father, George Green. George, who owned a large Upper Nyack farm, once encountered a runaway slave in his vineyard. The fugitive, as Green recalled, was “safely directed to a haven of refuge.” While the precise location of this haven remains unknown, the account suggests it was nearby—perhaps even at Lochbourne.

Lochbourne’s basement architecture adds intrigue. Its design includes several old foundations and rooms, one of which features a sturdy door and a narrow window with a wooden shutter. This unusual window seems impractical for most uses but could provide a concealed view outside. Could this room have served as George Green’s “safe haven”? While speculative, the idea aligns with Lochbourne’s rich history.

Livermore’s Lochbourne Renovation

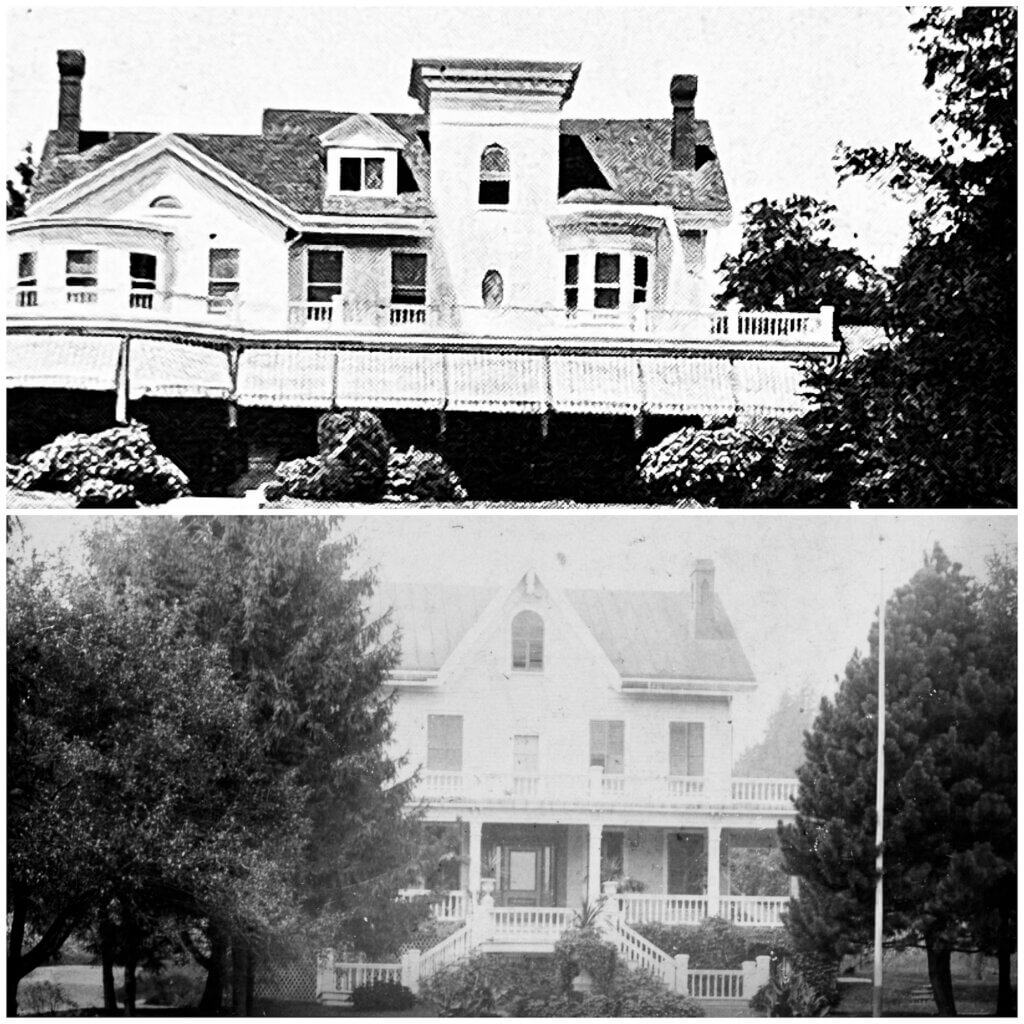

Charles Livermore’s acquisition of Lochbourne in 1865 ushered in significant changes to the estate. Shortly after purchasing Dr. Allen’s farm, Livermore likely added a second floor and expanded the home’s depth. Opinions differ on the architectural style of his renovation.

The application for the National Register of Historic Places states that Livermore’s addition favored an Italianate design. Nyack has numerous examples of this design from the mid-1800s including the Depew House at 50 Piermont Avenue, both of which display hallmarks of the style, such as flat roofs, cupolas, and symmetrical layouts.

However, an 1870s cabinet photo of Lochbourne hints at a different aesthetic. The image depicts a center-hall Carpenter Gothic style with matching elaborate front staircases and a brick foundation. A front porch roof supported by classical columns, with a balustrade on top mirrors the current design. The photo also shows a circular second-floor window above the door and a peaked attic window, both of which still appear in Lochbourne today. As we shall see, these features appear in a circa1895 addition and Victorian renovation.

An 1880 article in The New York Times paints a vivid picture of the estate’s approach: a “neglected road” that led to a “deserted gatehouse” with “iron fountains, devoid of moisture and tumbling into ruins.” A dammed Upper Nyack Brook once fed these fountains, and while they have vanished, the pond remains as a testament to Livermore’s vision for the property.

Livermore & Spiritualism

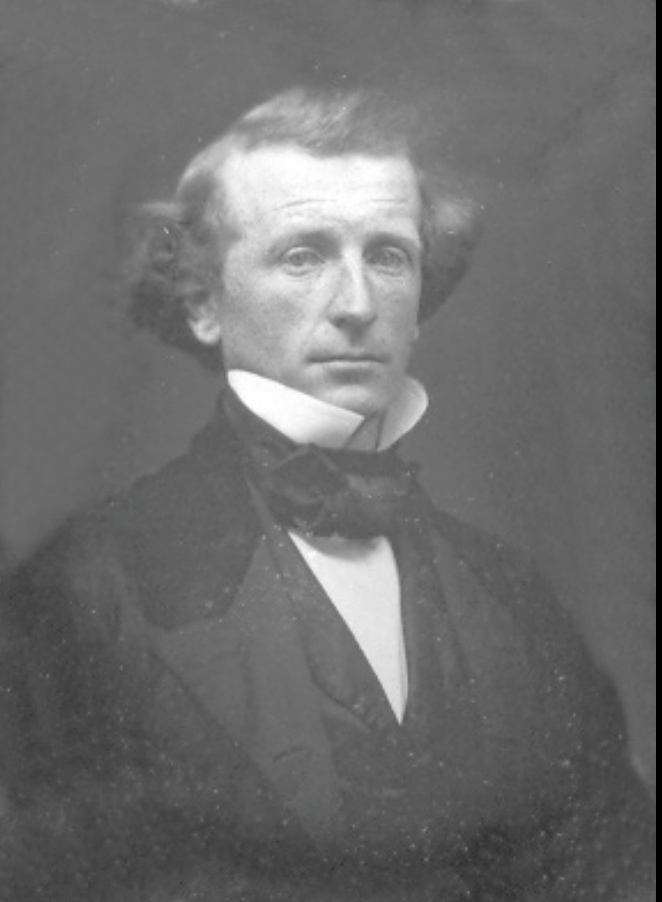

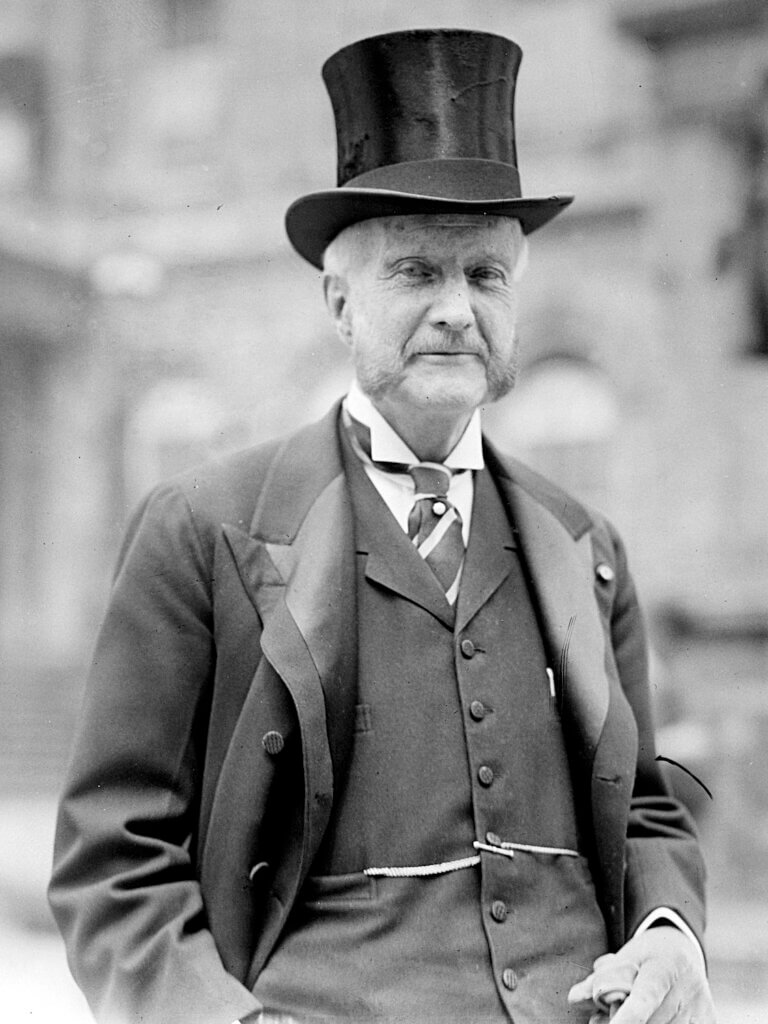

Livermore earned a fortune by funding companies aiding the Union in the Civil War. His partner, Henry Clews, went on to become one of the most important financiers of his time.

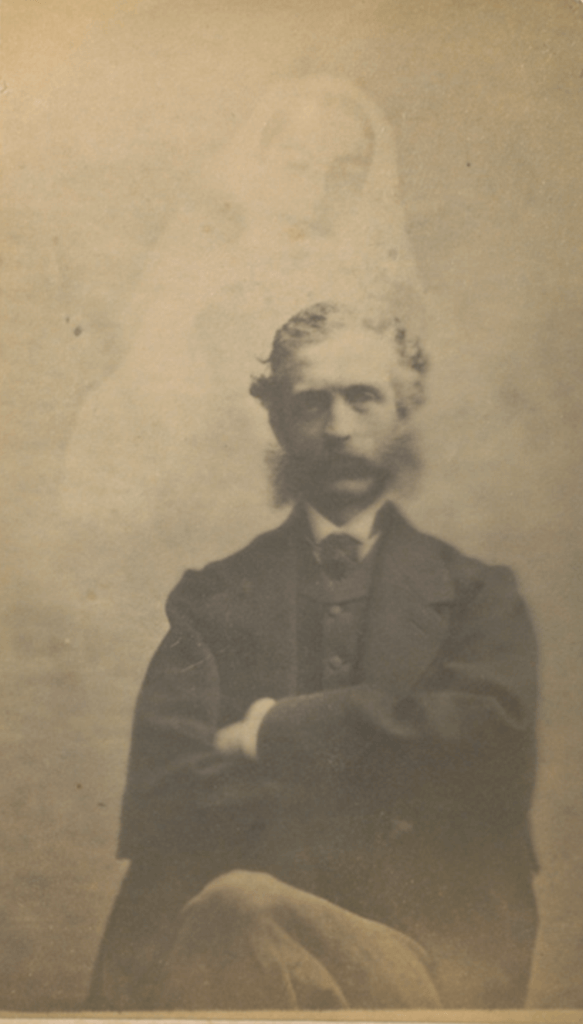

Charles Livermore spent summers at Lochbourne with his wife Marcia (who tragically died young), their three children, and a maid. Stricken with grief after Marcia’s death, he turned to spiritualism and attended 383 séances with renowned medium Kate Fox. He even sat for a spiritualist photograph by William Mumler

best known for his photograph of Mary Todd Lincoln with the deceased President in the background. Livermore later testified in Mumler’s defense during a fraud trial, which Mumler lost.

Lochbourne became both a summer retreat and a symbol of Livermore’s success. Livermore lived a remarkable life, passing away at 91. He is buried in the family plot in Spencer, Massachusetts.

The Grain Baron – John Carscallen

In 1890, John Dulmage Carscallen (1832–1906) purchased Lochbourne, marking the start of a new chapter for the estate. Born in Canada, the Carscallen family moved to the United States when John was a boy, eventually settling in Jersey City, New Jersey. There, John became a successful grain merchant and married Martha Ann Falkenburgh in 1863. Their son, Charles Sumner Carscallen (1863–1939), followed in his father’s footsteps, joining the family grain business as he came of age. In addition to managing the grain enterprise, John served as president of the Third National Bank of Jersey City.

During the late 19th century, the family began spending their summers in Nyack, initially staying at the rectory of Reverend Frank Babbitt at the corner of Franklin Street and DeCantillon Avenue (later Third Avenue).

In 1893, Charles met Marie Louise Lauderback of Brooklyn aboard a yacht traveling to Nyack-on-Hudson, as Nyack was then called. It was love at first sight. After a brief engagement, the couple married and moved into John’s summer home at Lochbourne, prompting John Carscallen Sr. to relocate to Brooklyn.

The Gilded Age Comes to the Neighborhood

The 1890s brought expansion and opulence to Nyack’s North Broadway area as the Gilded Age flourished. The Carscallens made significant improvements to Lochbourne, paralleling the renovations undertaken by their neighbors, the Crumbies, at Glenholme. It was likely the Carscallens who bestowed the estate with the name Lochbourne, reflecting the Scottish-inspired names of nearby properties such as Glenholme and Glen Iris.

In 1892, the neighborhood underwent a major transformation when the village widened North Broadway near the bend south of the Old Stone Meeting House. Neighbor Frank Crumbie generously allowed the village to use part of his property for the road expansion, ensuring that Carscallen’s iconic willows lining the street were preserved. Unlike many estates on North Broadway, Lochbourne did not feature a streetside wall. Instead, it boasted a gatehouse and a sweeping lawn leading up to the house. This lawn, which included a fountain, was one of the estate’s most striking features

The Dramatic 1895 Renovation

Around 1895, Lochbourne underwent a major expansion, evolving into its present form with a blend of Italianate and Colonial Revival styles. A central Italianate tower replaced the original central eave. The house’s footprint was expanded southward to include new rooms and a two-story corner bay window on the southeast side. A large, sweeping front porch, supported by a tall stone foundation with arched openings, wrapped around the bay window to a new porte-cochère entrance. Additional features included a porch awning, a second-floor bay window, and a third-story dormer, all contributing to the estate’s updated appearance. Doric columns supported the porch roof, and remnants of an ornate porch balustrade remain preserved in the old carriage house.

The driveway was redesigned to curve gracefully up to the porte-cochère before circling the house. During these renovations, the Carscallens likely added the carriage house, further enhancing the estate’s grandeur.

Social Life in Nyack’s Gilded Age

The Carscallens, particularly the newlyweds Charles and Marie, became prominent socialites in Nyack during their summer stays at Lochbourne. The estate hosted lively events, such as a “blind euchre” party organized by Mrs. Carscallen for 25 to 30 women. Players displayed their hands to others without seeing them themselves, competing for prizes like a silver-encased cologne bottle and a silver tape measure. Refreshments were served on the porch, adding to the merriment.

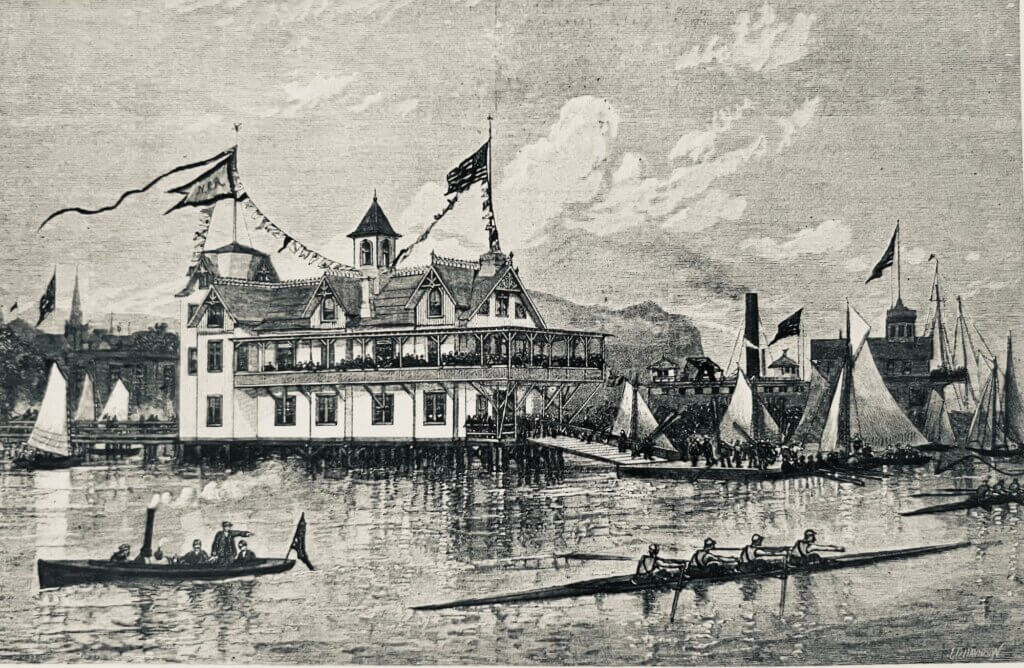

Charles and Marie also actively participated in the Nyack Rowing Association, where Charles was a member. Mrs. Carscallen and neighbor Mrs. Leroy Frost collaborated on organizing charity events for the Women’s Exchange of Nyack at the clubhouse.

The couple’s social activities often centered around the nearby Nyack Country Club, a hub for the town’s elite. In 1895, Charles served on the club’s executive committee, helping to establish a new golf club and renovate the tennis courts along North Broadway. He also contributed as a member of the House Committee. Unfortunately, the club’s events included minstrel performances, a reminder of the racial insensitivities of the era. Mrs. Carscallen served on the club’s entertainment committee, further solidifying the couple’s status as pillars of the community’s social scene.

Winston Churchill’s Stay at Lochbourne

Winston Churchill was an extremely successful American author before the British Winston Churchill gained fame.

Adding to Lochbourne’s fascinating history, Winston Churchill, a best-selling American novelist, rented the tower room in the estate house in 1898, drawn by its serene setting and inspiring vistas. During his stay, he penned Richard Carvel, a novel that sold two million copies and cemented his literary success. Churchill’s time at Lochbourne was marked by creativity and connection to the community. He was often seen walking to “downtown” Upper Nyack, where he played checkers with locals at Harry Perry’s meat market, a store situated at the corner of Broadway and Castle Heights. This small but lively store served as a hub of social interaction, and Churchill’s presence there left a lasting impression.

Harry Perry, so inspired by these interactions, named his son Winston Churchill Perry in honor of the novelist. Perry carried on the tradition by naming his son Winston Perry Churchill Jr. who became a noted architect and longtime resident of Upper Nyack.

Transition to Modern Times

In our next episode we will look at the changes in the estate in the 20th century along with the interesting personages who lived there beginning in 1905.