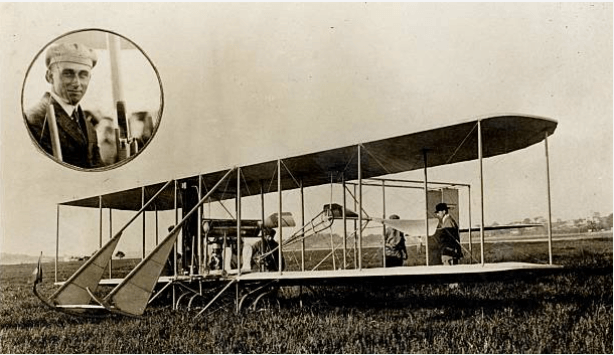

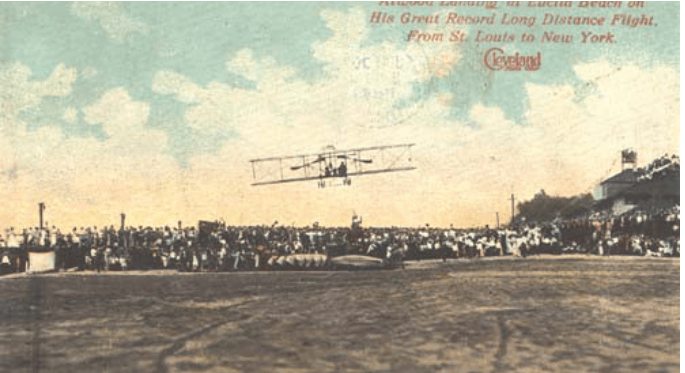

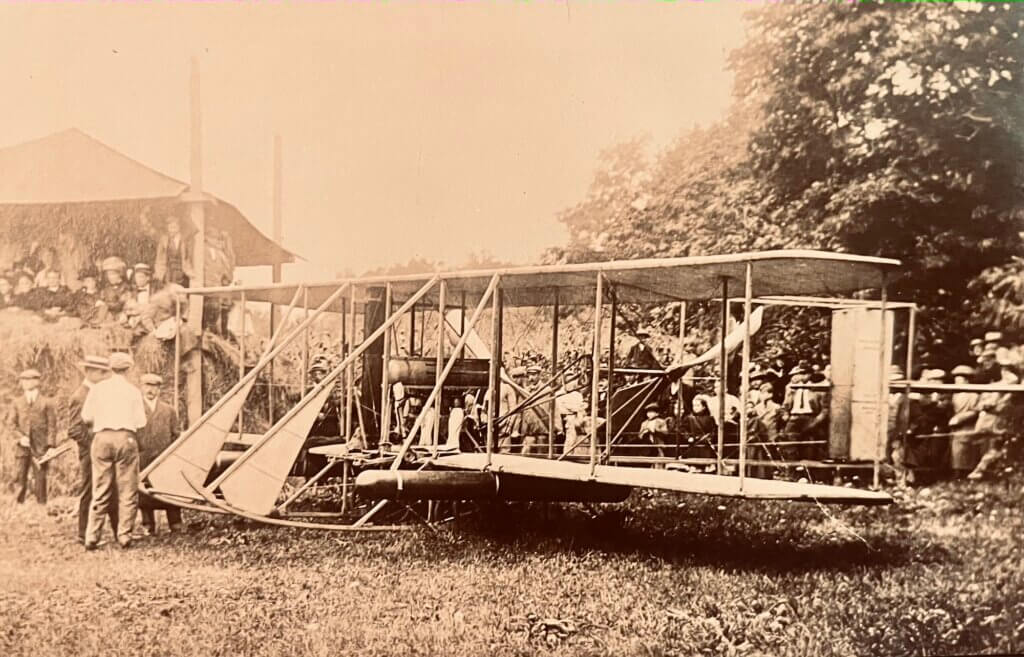

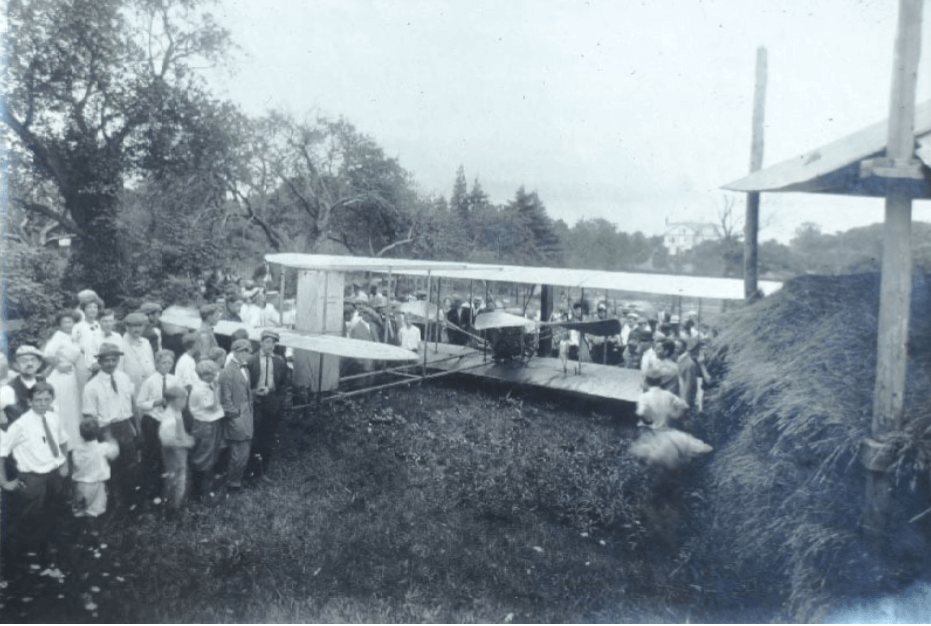

Back on August 24, 1911, the skies above Upper Nyack bore witness to a spectacular event when Harry Atwood’s biplane executed a daring emergency landing in a nearby field. This momentous occasion marked the first time the villagers had the privilege of gazing upon a magnificent flying machine. Atwood, an audacious pioneer of aviation, found himself in the final leg of his remarkable journey from St. Louis to New York City via Chicago, a feat that at the time stood as the longest nonstop flight undertaken by a single plane. The imagery of an airplane devoid of a cockpit, sophisticated navigation tools, and landing wheels is a stark contrast to the marvels of contemporary aircraft.

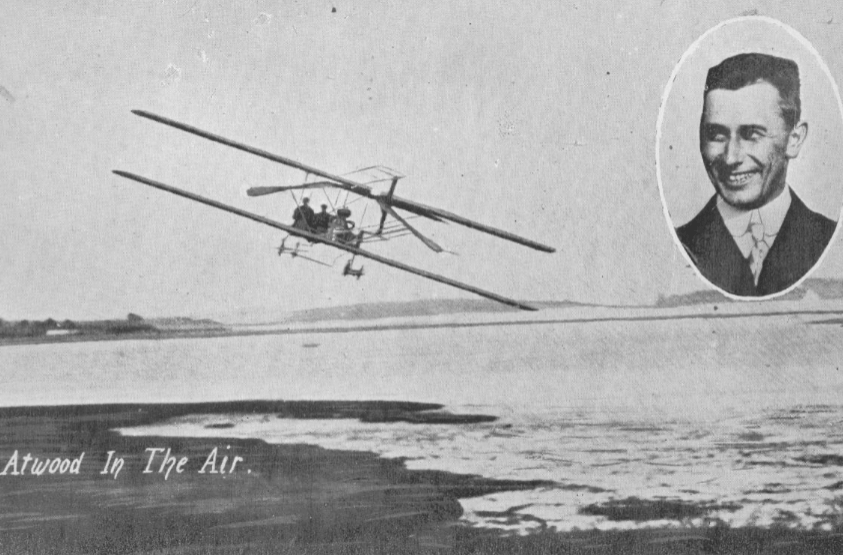

Guiding his plane at a brisk 50 mph, powered by an engine comparable in strength to today’s lawnmowers, Atwood occupied a precarious spot on the lower wing exposed to the elements with the propellors behind him, deftly maneuvering the aircraft using hand and foot controls. His epic journey garnered national attention, drawing throngs of spectators during his refueling and overnight pit stops. The emergency landing he executed that day would etch its place in Nyack’s annals as one oits most significant events

The worst box I’ve have been in since leaving St. Louis.

Harry Atwood

Now, let’s delve into the riveting saga of Harry Atwood, his groundbreaking cross-country odyssey, and his unforgettable impromptu stay in Nyack.

Harry Atwood: A Trailblazing Aviator

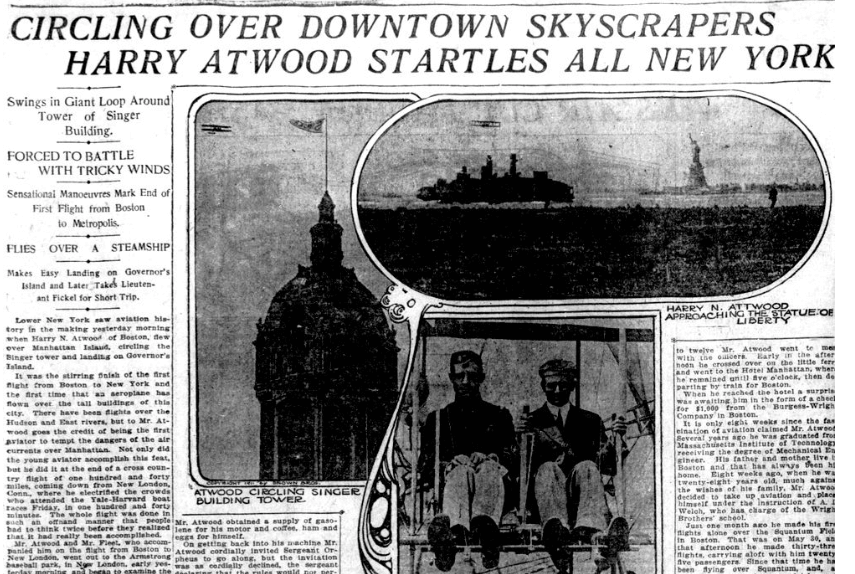

In the years leading up to 1910, flights were fleeting and seldom, leaving most Americans with minimal exposure to the marvel of flight. Enter Harry Atwood, a true daredevil of the skies, who ventured into the realm of aviation with relentless determination. Learning the ropes at the Wright Flying School near Dayton, Ohio, Atwood swiftly acquired his own biplane and set out to break records. He carved his name in history as the daring individual who introduced airmail delivery, dropping mail bags from the skies over Saugus, MA, near Boston. In January of 1911, he completed a remarkable flight from Boston to New York, making a sole stop en route and securing the coveted New York Times Trophy.

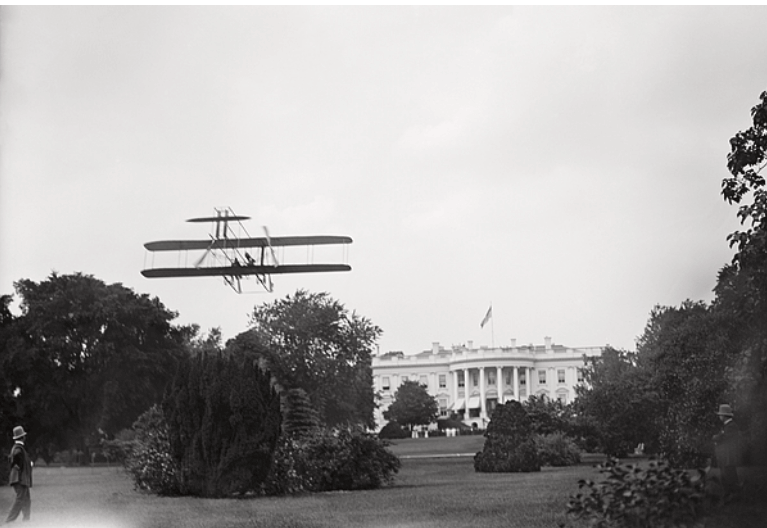

The month of July witnessed Atwood’s flight from New York City to the nation’s capital, Washington, D.C. It took three attempts to achieve this feat. During the initial takeoff, a mischievous white bull terrier disrupted proceedings, damaging a wooden propeller. Undeterred, Atwood pursued his goal, even surviving a crash from a height of 75 feet during the second attempt. The third endeavor saw him triumphant, as he gracefully maneuvered his plane around the Washington Memorial on the Mall and touched down on the White House Lawn.

The Epic Flight from St. Louis to New York City

Merely a month later, Atwood dared to venture further, embarking on an even more audacious challenge: a flight from St. Louis to New York City. The stakes were high, with planes cruising at around 50 mph and demanding frequent refueling stops. Atwood’s journey took him through cities like Chicago, Sandusky, Dayton, and Buffalo. At every stop, a rapt audience gathered, some even climbing ladders to rooftops or assembling at open spaces like baseball fields to witness this airborne marvel. Telegraph operators worked diligently to provide real-time updates on his progress, while the pages of the New York Timesfeatured a captivating graphical flight log, keeping the nation enthralled.

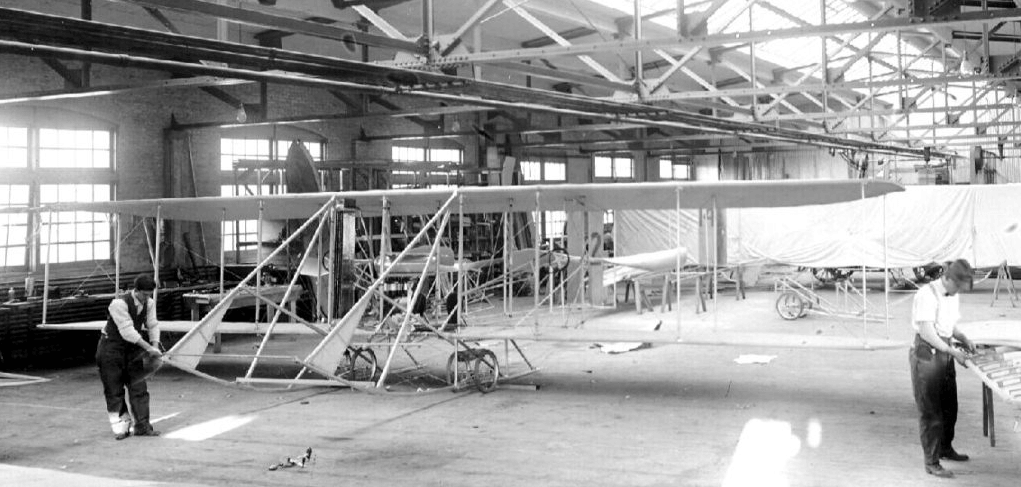

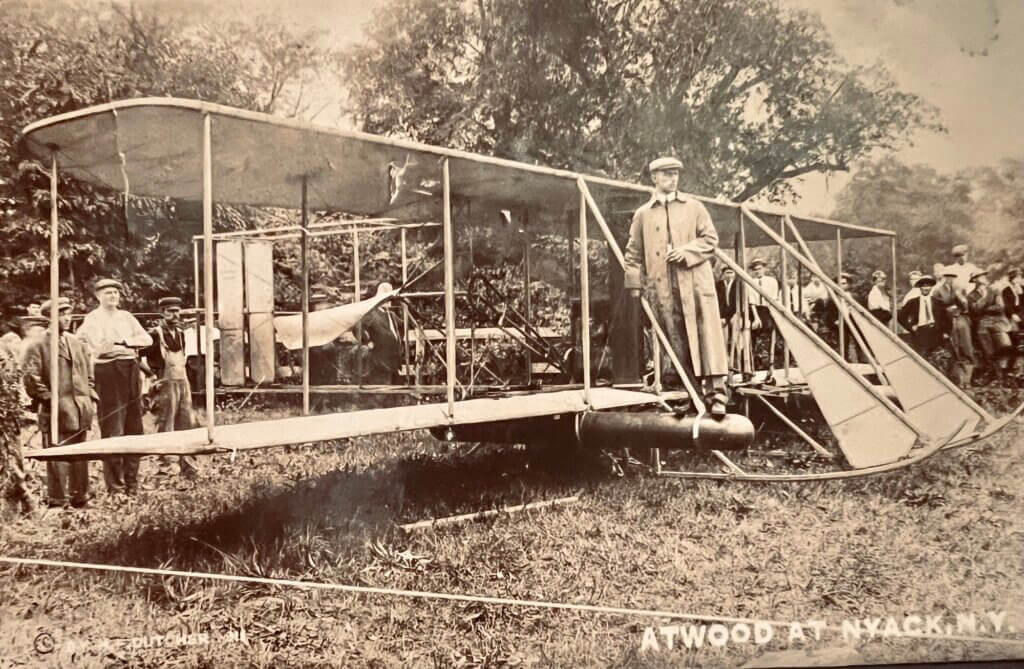

Navigation in those times was rudimentary, often involving tracing railroad lines to discern town names on station signs. Atwood’s aircraft, the Wright Model B biplane, was equipped with a modest 4-cylinder gas engine propelling twin propellers positioned behind the wings. The aircraft spanned 39 feet across and was 30 feet in length. Control came through manipulation of two foot-pedals and two hand-levers. Perched daringly on the lower wing, Atwood braved the elements with no goggles, helmet, or gloves – just his signature reversed driver’s cap, complemented by a suit and tie.

Eager Crowds Watch

Each landing was a spectacle, greeted by eager crowds. With a simple lunch bag and a small brown valise containing essentials like a change of clothes, toothbrush, a topographic map, and a handful of tools, Atwood embodied the epitome of adventurous spirit. Upon landing, dressed immaculately in a Norfolk suit, he exuded the composure of a traveler stepping off a Pullman car.

Accompanying Atwood on his journey were two mechanics who followed by rail, often toiling overnight to mend the aircraft’s mechanical hiccups. At times, the challenges piled up, with Atwood grappling with a whopping five mechanical problems in one day.

“Two Bird Hops Away from NYC”

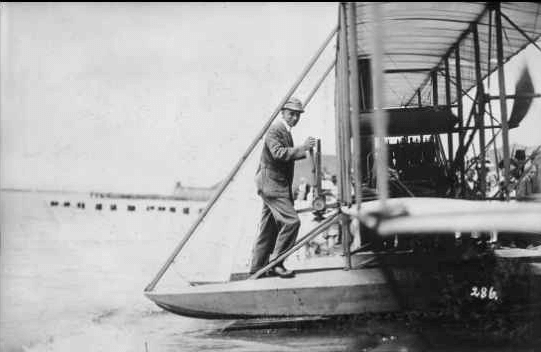

As August 24 dawned, Atwood’s final stretch was earmarked for “two bird hops” to New York City. Beginning his day at the break of dawn in Castleton-on-Hudson, the previous night’s landing had drawn a crowd – albeit smaller due to a farmer’s admission fee. Adding pontoons for a water landing at Governor’s Island, Atwood’s plans were slightly thwarted by an uncooperative engine. Quick thinking mechanics replaced a spark plug with one sourced from an automobile.

With throttle open, Atwood rocketed past Germantown, setting a record for flight distance as he sailed over the eastern bank. Crossing the river, he circled low over Kingston Point, acknowledging the cheering throngs lining the riverbanks. Poughkeepsie welcomed him with a symphony of bells, factory whistles, and spirited cheers from the railway bridge. Atwood playfully exchanged greetings with ferryboat passengers as he zoomed by. Traversing the eastern shore and then crossing to West Point, Atwood found the parade grounds teeming with soldiers. Crowds in those days had no sense of how much space an airplane required to land. Opting for caution, he flew across the river to Garrison, refueling with automobile gas.

Around the Hook

Atwood later confessed that the journey down the Hudson River held a special place in his heart, relishing the breathtaking mountainous landscapes. However, the Hudson Highlands and the Palisades posed challenges, chiefly a dearth of suitable landing sites. This challenge became a reality when he began losing engine power near Ossining. Seeking guidance, he swooped down towards the pier of the New York Trap Rock Company at Rockland Landing, soliciting advice from the men there. Unwilling to chance a landing on the choppy waters of the Tappan Zee due to his untested pontoons, Atwood received shouted directions to a suitable landing spot around Hook Mountain. Summoning every ounce of skill, he managed to gain altitude up to 1,000 feet and deftly rounded the Hook.

As the plane came into view, Nyack’s dockside spectators erupted in anticipation. The Peerless Finishing Company punctuated the moment with three resounding horn blasts, announcing Atwood’s impending arrival. And then, in a matter of moments, the plane vanished from sight.

Touchdown in Upper Nyack

In the year 1911, Upper Nyack was a medley of sprawling farms and grand riverfront estates. The landscape, despite its beauty, offered scarce flat expanses, making landing a daunting proposition. Yet, Atwood’s expertise guided him to a small haven near North Broadway, once the territory of the George Green farm. Positioned adjacent to Lexow Avenue, a pocket-sized pasture measuring 150 feet awaited, adorned with fruit trees that formed a picturesque frame across from Belle Crest, Walter Davies’ splendid dwelling. Atwood’s landing, he would later recount, felt like navigating “the worst box I’ve been in since leaving St. Louis.” His remarkable skill prevented a hayrick collision on landing, and the soft ground yielded beneath the weight of his aircraft, touched by a light rain.

Villagers surged forth, a tide of humanity converging upon the scene. Leading the charge was Butch Logue, a 14-year-old lad who would later earn his stripes as a World War I veteran and become a familiar face at O’Donoghue’s on Main Street. Abandoning his bicycle mid-route, Butch arrived on the scene, finding Atwood unharmed. On returning to his bicycle, Butch’s meat delivery had mysteriously vanished, possibly pilfered by one of the curious villagers who had flocked to witness history in the making.

To maintain order and deter souvenir hunters, a village constable quickly made an appearance. Some took the liberty to pencil their names onto the canvases of the aircraft, already adorned with countless signatures. This practice of mementos was not unique to Nyack – at other stops along his 1,300-mile journey, enterprising vendors hawked pencils, facilitating the eager public in leaving their mark.

A Night to Remember in Nyack

The exigencies of the situation soon became apparent – Atwood discovered a broken engine connecting rod. With his mechanics already en route to New York City carrying the plane’s spare parts, Atwood faced a daunting challenge. He made his way to the residence of Wilson Foss, one of Nyack’s most prosperous individuals at the time, seeking assistance. Foss facilitated a call to Sheepshead Bay, a lifeline to his mechanics. Concurrently, Atwood reached out to the Hudson Yacht and Boat Company (later to become Peterson’s Boat Yard) in Upper Nyack Landing, exploring the possibility of repairing the damaged rod. The capable hands of machinist Henry Kicks toiled throughout the night, working on mending the crucial component.

Even as the night progressed, Atwood partook in a hearty lunch at the St. George Hotel, later joining the Davies family for dinner at their abode, situated just across from his aircraft. Walter Davies, a retired manufacturer, generously offered to fell some of his locust trees to facilitate Atwood’s departure. The night unfolded, and Atwood rested his head at the St. George Hotel, brimming with anticipation for the following day.

Departure

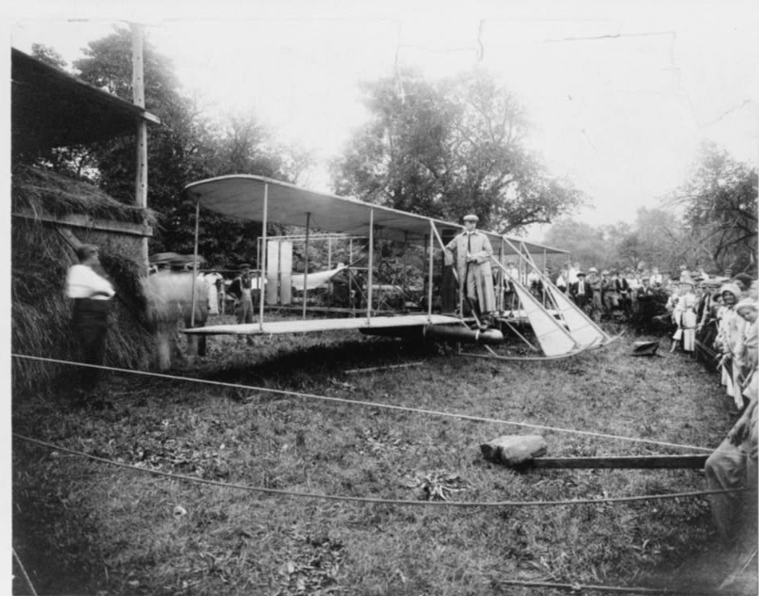

As the sun rose on August 25, 1911, a light mist hung in the air, and the winds proved contrary. Undeterred by these challenges, Atwood rallied the villagers who had stood by him through the night, beseeching their aid in maneuvering the plane over two fences, into an open field belonging to Miss Elizabeth Green.

The previous night’s activities had seen the felling of fruit trees on her property, a makeshift solution endorsed by Atwood to allow for a smooth landing. The makeshift runway saw further alteration, with a few more trees making way for the takeoff. In a quick trip to town, Atwood acquired dry clothes from Neisner’s men’s wear store, adding a duster to his attire, an iconic ensemble preserved in the photographs from that monumental day. Atwood enlisted spectators to move the plane to the makeshift runway.

New York City Bound

“I really think I touched the branches on both sides as I went into the air.”

Harry Atwood

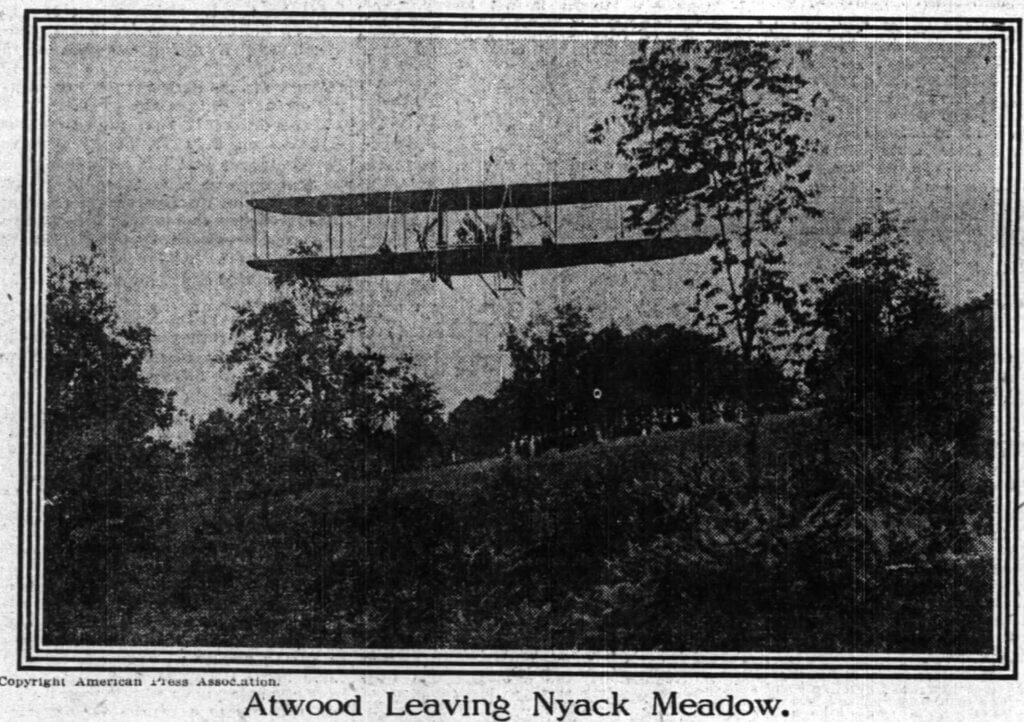

The engine, dampened by the morning mist, initially refused to cooperate. A touch of gasoline and an unfortunate ignition led to a blaze quickly extinguished by sand. With propellers finally spinning, Atwood seized the moment, the aircraft surging forward and taking flight through the narrow passage between the trees. Atwood recalled, “I really think I touched branches on both sides as I went into the air.”

Harnessing the full power of his plane, Atwood pushed it to its limit, countering the weight of the dampened canvas. Nyack gradually receded into the distance, an audience left gazing in awe. At his final stop on Governor’s Island, Atwood reflected, “Well, I am glad it ended,” alluding to the tantalizing prospect of a coast-to-coast journey.

Atwood’s triumph didn’t end at the skies; he not only secured his prize (despite the challenges of collection) but also captured the hearts of Nyack’s inhabitants. Their introduction to flight, the rarest of spectacles in those days, had thrust our quaint village into the spotlight of national news, leaving an indelible mark on history.

Michael Hays is a 35-year resident of the Nyacks. Hays grew up the son of a professor and nurse in Champaign, Illinois. He has retired from a long career in educational publishing with Prentice-Hall and McGraw-Hill. Hays is an avid cyclist, amateur historian and photographer, gardener, and dog walker. He has enjoyed more years than he cares to count with his beautiful companion, Bernie Richey. You can follow him on Instagram as UpperNyackMike