“The most prominent building in Nyack when seen from the river is the Tappan Zee House.”

—Joseph Richards, The Independent, August 17, 1861

A Golden Age on the Hudson

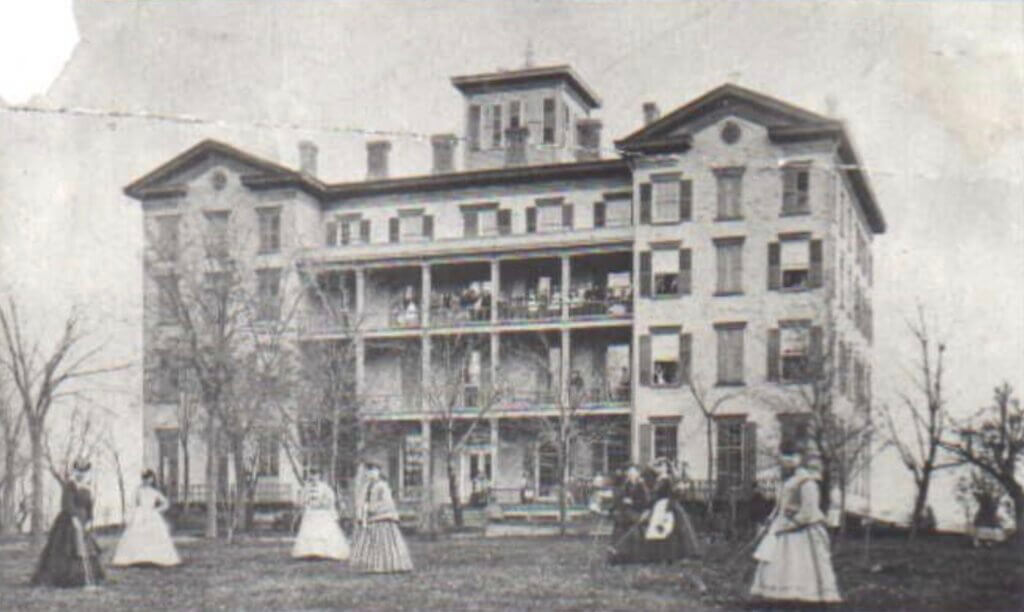

For over half a century, the Tappan Zee House stood as one of the grandest summer resorts on the Hudson River, drawing generations of visitors to Nyack in the height of the Gilded Age.

It was one of three major resort hotels that transformed Nyack from a modest river village into a summer destination for wealthy New Yorkers. The Prospect House, perched atop South Mountain, was known for its sweeping views, wraparound porches, and open-air clambakes. It drew guests from New York and Philadelphia and hosted elegant lawn tennis tournaments and masked balls. The Pavilion, located on a hill top above Main Street at the foot of Catherine Street, catered to middle-class families and day-trippers. Its location near downtown, spacious lawn, and musical evenings gave it a friendly, festive reputation.

“If the Tappan Zee House was elegance, the Pavilion was charm—closer to town, closer to the heart.”

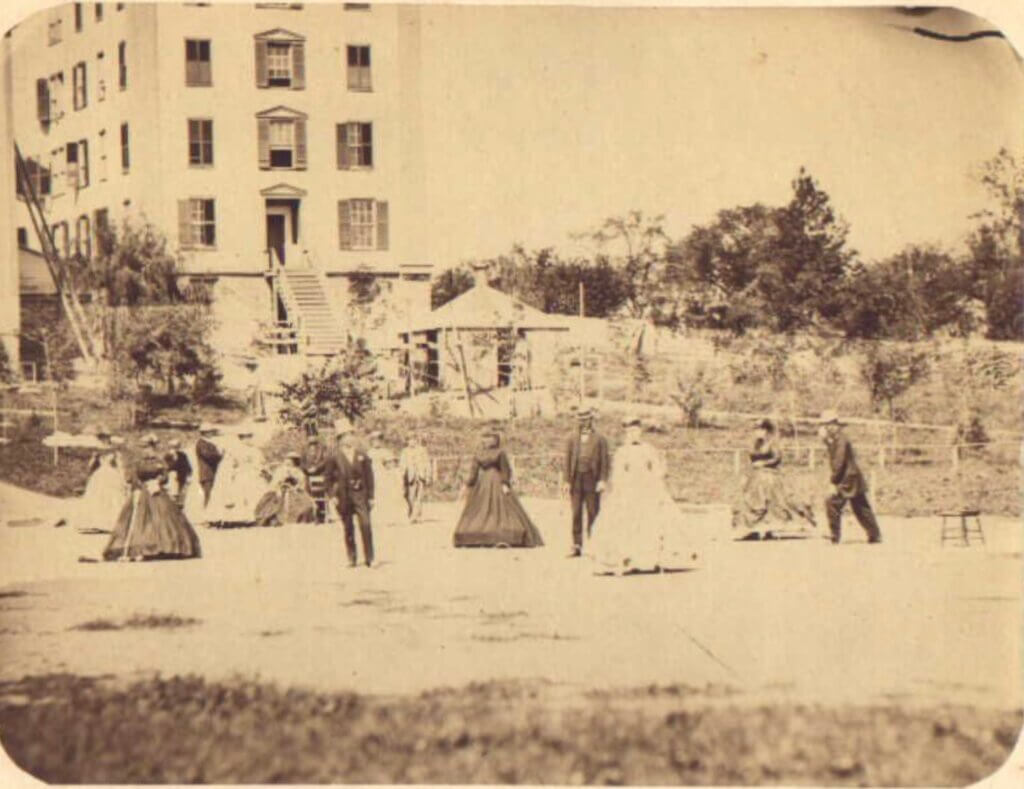

Guests from all three resorts sometimes mingled for baseball games, lawn tennis, or evening dances. But even among its celebrated peers, the Tappan Zee House stood apart—rising from ten shaded acres that sloped gently to a private beach and pier.

“No Malaria, No Mosquitoes”

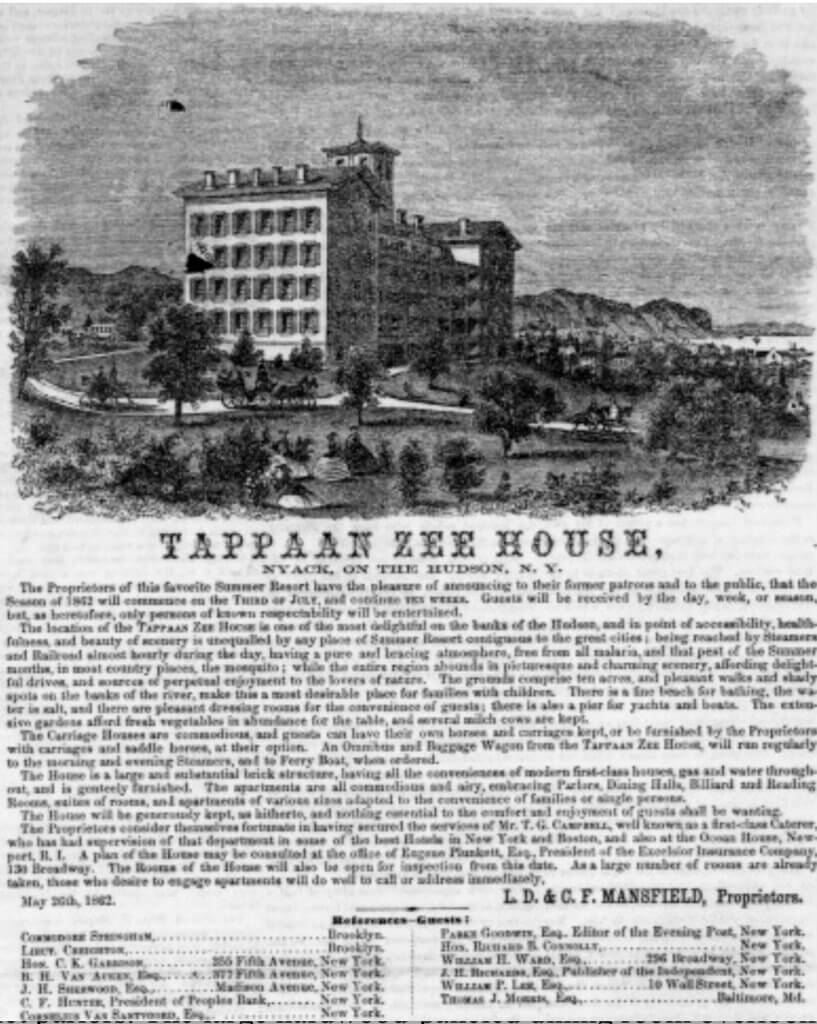

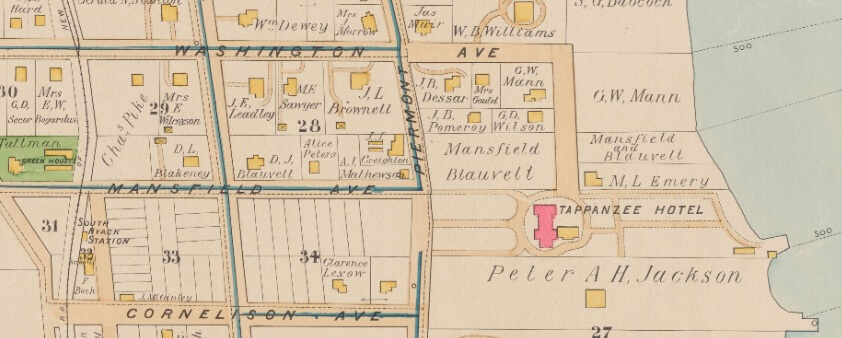

Trains stopped directly at the Mansfield Avenue (South Nyack) station on the hotel’s grounds. Steamboats arrived at the Nyack docks several times a day. A waiting omnibus met guests dockside and carried them up an elm-lined drive, often lit with lanterns for evening arrivals. For a time the steam yacht Royal anchored off the premises every night. A hotel advertisement from around 1870 promised a “pure and bracing atmosphere… no malaria, no mosquitoes.”

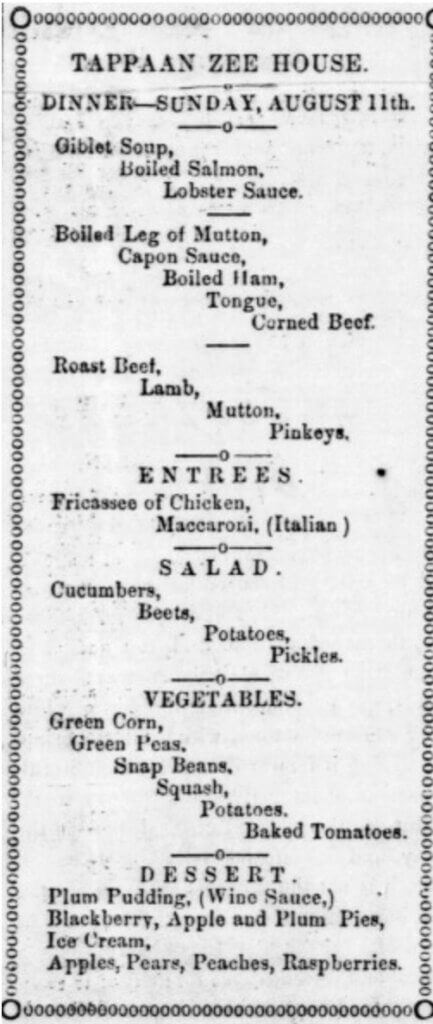

The estate offered more than comfort—it promised health. Guests enjoyed croquet courts, rose gardens, a saltwater bathing beach with bathhouses, yacht landings, stables for horseback riding, reading parlors, and billiard rooms. Meals featured vegetables from the hotel’s garden and fresh milk from cows kept on-site. The drinking water, celebrated for its clarity and taste, flowed from nearby mountain springs.

From Boarding School to Luxury Resort

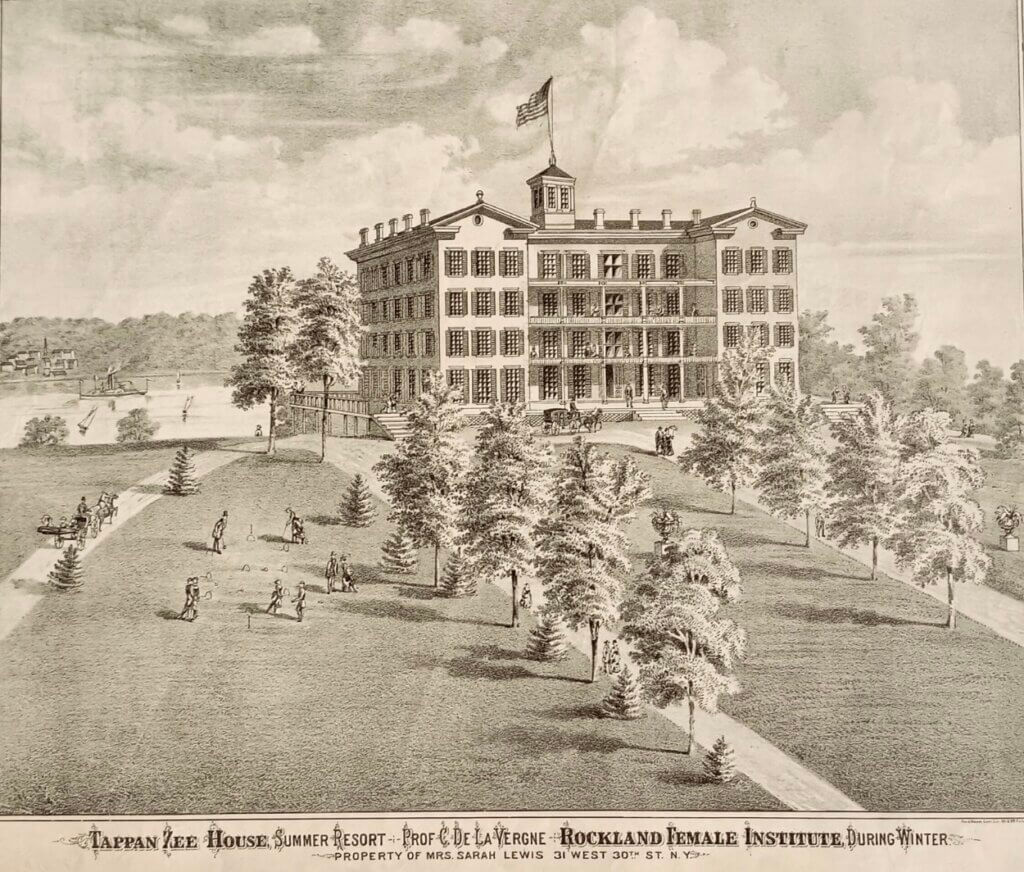

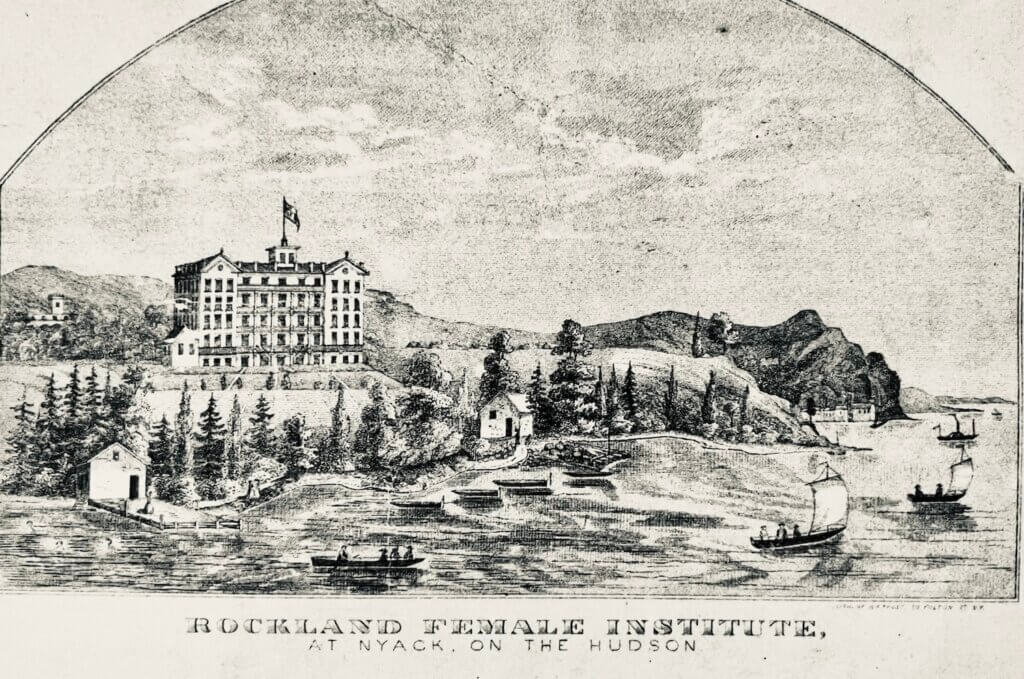

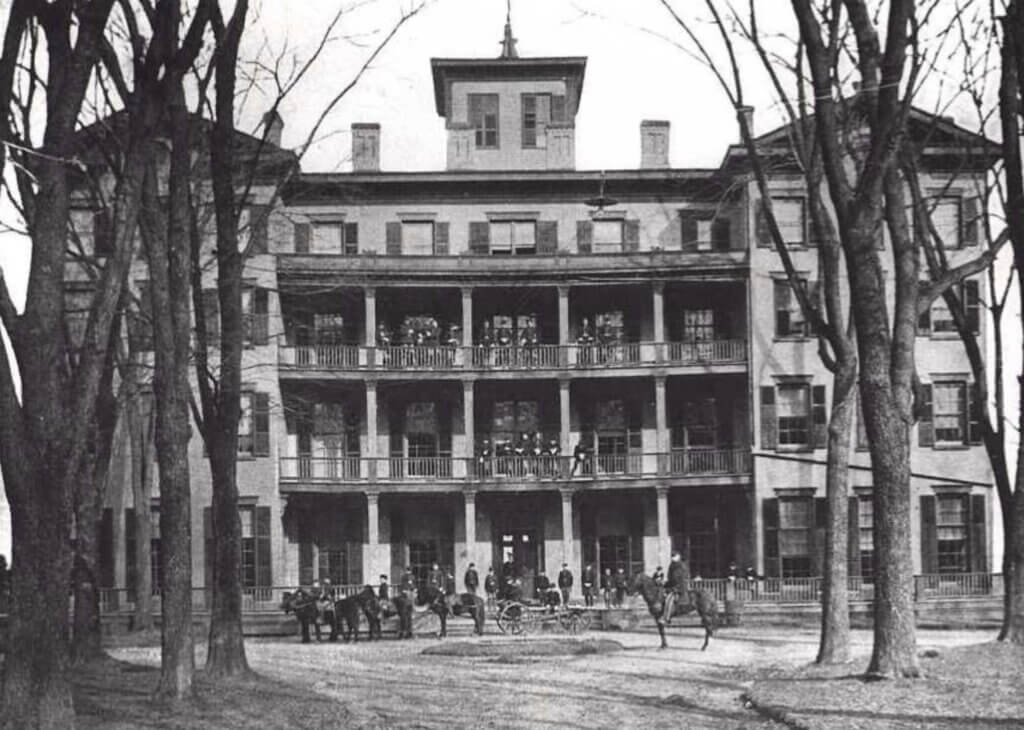

The Tappan Zee House had unique origins. In 1856, it opened as the Rockland Female Institute, one of the region’s earliest schools for the higher education of women. The stately four-story brick building in the Greek Revival style, with 50 rooms, river-facing balconies, classical columns, broad porches, and a cupola offering sweeping views, was a model of progressive architecture and ambition.

During summer recess, the building hosted city vacationers. By 1857, the Tappan Zee Inn welcomed its first guests, launching its dual identity as both a school and summer resort. In 1875, the school closed permanently, and the building was transformed into a full-time hotel.

“Unequaled by any summer resort contiguous to the great cities.”

Rockland County Journal, May 31, 1862

During the Civil War era, the resort was so popular that cots had to be placed in the hallways to accommodate overflow crowds. Visitors came from New York, Brooklyn, Philadelphia, Baltimore—and even as far away as Mobile, Alabama.

A Life of Leisure and Luxury

With its scenic lawns, airy verandas, and cooling river breezes, the Tappan Zee House epitomized Gilded Age luxury. Guests lounged in riverside gazebos, played croquet beneath elms, or read in quiet parlors. The large hardwood-paneled dining room overlooked the Hudson, where boats passed against a backdrop of cliffs and shimmering light.

Two private cottages on the grounds—The Villa and The Kathrina—provided added privacy for extended stays. Guest could rent horse-drawn carriages or bring their own from home. The hotel even hosted events for local elites and diplomats, noted in both The New York Times and regional society columns.

The Hotel Expands

The 1880s and 1890s marked the Tappan Zee House’s golden years. Under the management of George Bardin, who later became the owner of the Hotel St. George, and W. W. Palmer, who also managed the Magnolia Hotel in St. Augustine, the hotel underwent significant renovations.

Gas lighting, electric bells, shaded piazzas, and elegantly furnished parlors were added. Renovation opened up the first floor to create a grand hall, from which two wooden stairways led to the upper floors. A large addition on the east side included a new dining room overlooking the river, accessible through an arched oening from the hall. A billiard room and a dining room for servants and nurses occupied space below the dining room. Above the dining room, twenty-two new river-view rooms provided expanded accommodations for guests. A new six-foot stone wall replaced the rough stone shoreline. A promenade led to the docks, bathhouses, and a pavilion. A stone stairway led to the beach.

The Proprietor’s Ball: Moonlight and Lanterns

The highlight of every summer season was the Proprietor’s Ball. Hundreds of guests arrived—some staying at the hotel, others sailing up from the city, and others from Nyack. The tree-lined allee leading to the hotel was strung with colored lanterns. The porches overflowed with potted palms, hanging vines, and ferns. Inside, Professor E. L. Cranmer’s orchestra played behind a lush curtain of palms and ferns as elegantly dressed guests glided across the floor, spinning through waltzes, lancers (a quadrille), and lively polkas.

“It was like something out of a dream—the lights, the music, the gowns… the Tappan Zee Ball was the high point of every summer.”

Gilded Age dancers dressed in formal attire

Dinners were elaborate. In one year, the hotel steward carved an entire hunting scene from ice as a table centerpiece. After dessert and drinks in the parlor, dancing resumed into the early morning.

Games, Courtships, and Donkey Dances

The Tappan Zee House was more than elegant—it was lively. A friendly rivalry with the Prospect House included tennis tournaments and baseball games between hotel waiters. Social calendars were filled with masked balls, euchre parties, and themed events.

One season, the hotel hosted a 14-year-old guest’s birthday party, complete with “donkey dancing” and a ceremonial cake speech. Another summer brought an angling contest, followed by a formal collation for over 30 couples.

The hotel was also the setting for romance. Gertrude Palmer, daughter of the proprietors, met Charles Edward Leadley of South Nyack at a Tappan Zee social. The story goes that Leadley left his Wall Street job, followed her to Florida, and married her soon after.

Exclusion Behind the Elegance

Like many resorts of its era, the Tappan Zee House also reflected the prejudices of the time. In 1885, owner C. E. Munroe ran an ad in the New York Times explicitly opening the hotel “To Gentiles”—a euphemism used to exclude Jewish guests. The ad ran multiple times and was referenced by the Hebrew Tribune. Though common at Gilded Age resorts, the policy stands today as a reminder of the barriers behind the manicured lawns.

The Long Decline

As the 20th century approached, change came quickly. Steamboat travel declined, and with it, the flow of summer tourists. The Prospect House burned in 1898, and the Pavilion fell into decline. In 1907, the Tappan Zee House closed as a hotel.

New efforts followed. From 1895 to 1910, the building served as the Hudson River Military Academy. In 1918, the Nyack Club, formed by merging the Nyack Country Club and the Nyack Arts Club, attempted to revive the building as a private clubhouse. Local figures like DuPratt White led the effort. Though the building was renovated, the club defaulted on its first mortgage, and the hotel sat vacant through the 1920s and early 1930s.

The Final Fire

On the night of June 23, 1932, a neighbor on Glyn Byron spotted flames rising from the northeast corner of the building. The fire had started in the long-empty kitchen. Firefighters from every Nyack company responded—Mazeppa, Highland Hose, Empire Hook and Ladder, Chelsea Hook and Ladder, Jackson, and Orangetown.

They fought the blaze from balconies and inside the grand dining room. Just after the Mazeppa company exited the auditorium, the roof erupted in flames, shooting 40 feet into the sky before collapsing.

By morning, only brick shells stood. The river’s most elegant retreat was no more.”

Rockland County Evening Journal, June 24, 1932

The next day, firefighters returned to douse flare-ups smoldering in the ruins. The once-grand lawn became a hangout for teenagers, lovers in cars, and summer beachgoers—until a fence was finally erected to keep them out.

Faded Footprints on the Shore

Today, no physical trace remains of the Tappan Zee House. Its manicured lawns and lantern-lit dances have long disappeared, but its memory lingers in photographs, newspaper clippings, and the stories handed down across generations. The Tappan Zee House lives on not in bricks or timbers, but in story—a vanished chapter of Nyack’s golden age on the Hudson.

Mike Hays lived in the Nyacks for 38-years. He worked for McGraw-Hill Education in New York City for many years. Hays serves as President of the Historical Society of the Nyacks, Vice-President of the Edward Hopper House Museum & Study Center, and Upper Nyack Historian. Married to Bernie Richey, he enjoys cycling and winters in Florida. You can follow him on Instagram as UpperNyackMike.

Editor’s note: This article is sponsored by Sun River Health and Ellis Sotheby’s International Realty. Sun River Health is a network of 43 Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHCs) providing primary, dental, pediatric, OB-GYN, and behavioral health care to over 245,000 patients annually. Ellis Sotheby’s International Realty is the lower Hudson Valley’s Leader in Luxury. Located in the charming Hudson River village of Nyack, approximately 22 miles from New York City. Our agents are passionate about listing and selling extraordinary properties in the Lower Hudson Valley, including Rockland and Orange Counties, New York.