Hammers rang through the air and saws rasped as piles of brick and stone rose across Nyack during the Gilded Age. Downtown brick buildings took shape along Main Street. New churches anchored neighborhood corners. Factories expanded. Dozens of Queen Anne Victorians filled the once-open fields of South and Upper Nyack.

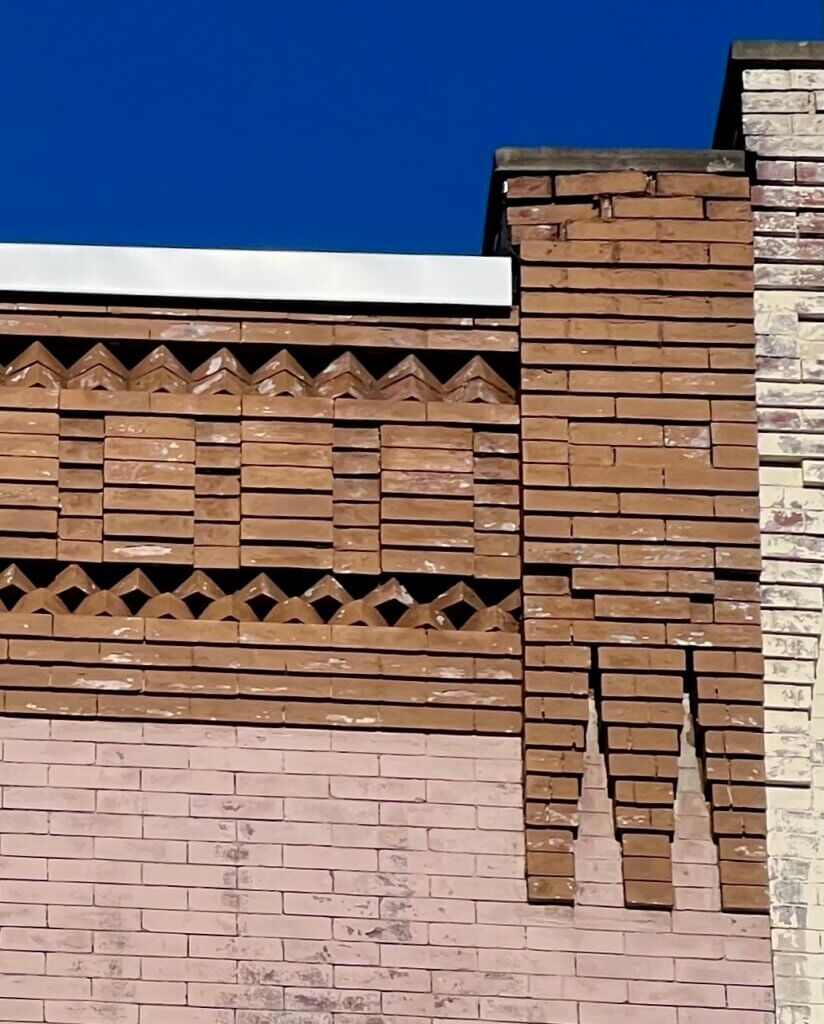

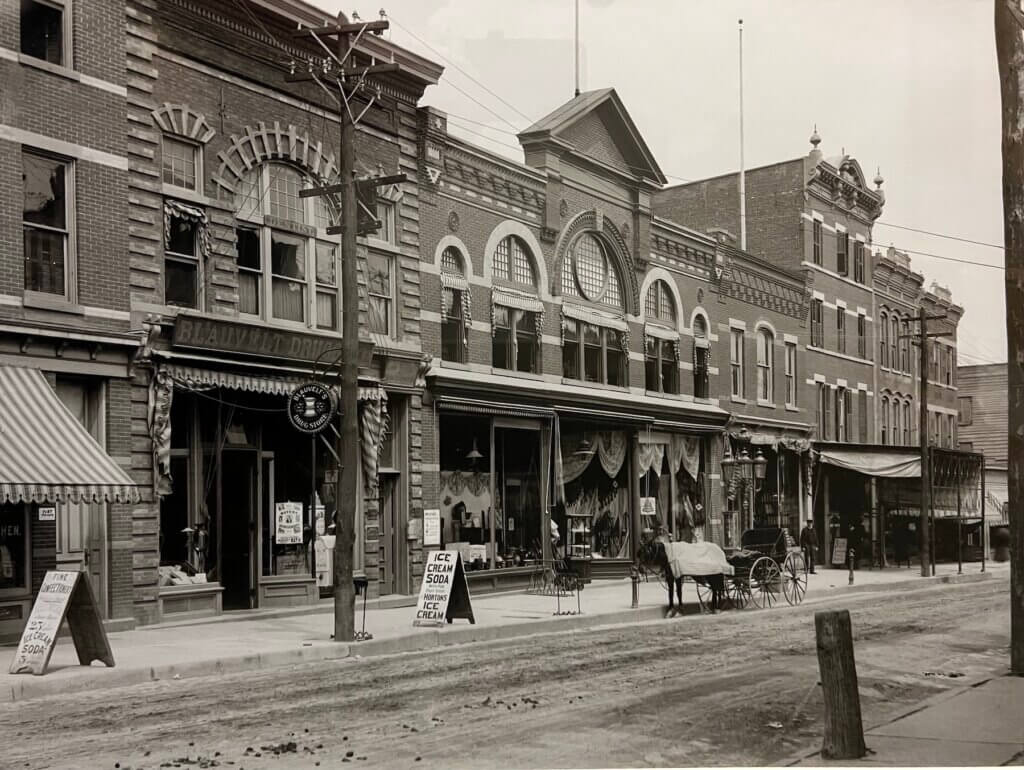

Examples of Magee brick work on Nyack’s Main Street

Behind this transformation stood a small group of craftsmen and builders. Architects such as the Emery Brothers and Horace Greeley Knapp supplied the designs. The DeBaun brothers and Charles McElroy handled much of the carpentry. None of it could stand without skilled masons. No mason left a deeper imprint on Nyack than John Magee, an Irish immigrant.

Magee’s output in the 1890s alone was astonishing. He erected major churches, including the expanded Reformed Church, now The Angel Nyack. He built commercial landmarks such as the Harrison & Dalley department store. His residential work ranged from modest homes to substantial stone and brick showpieces, including the Van Buren house at 191 South Broadway. For nearly four decades, anyone walking Nyack’s streets could see Magee’s work in progress.

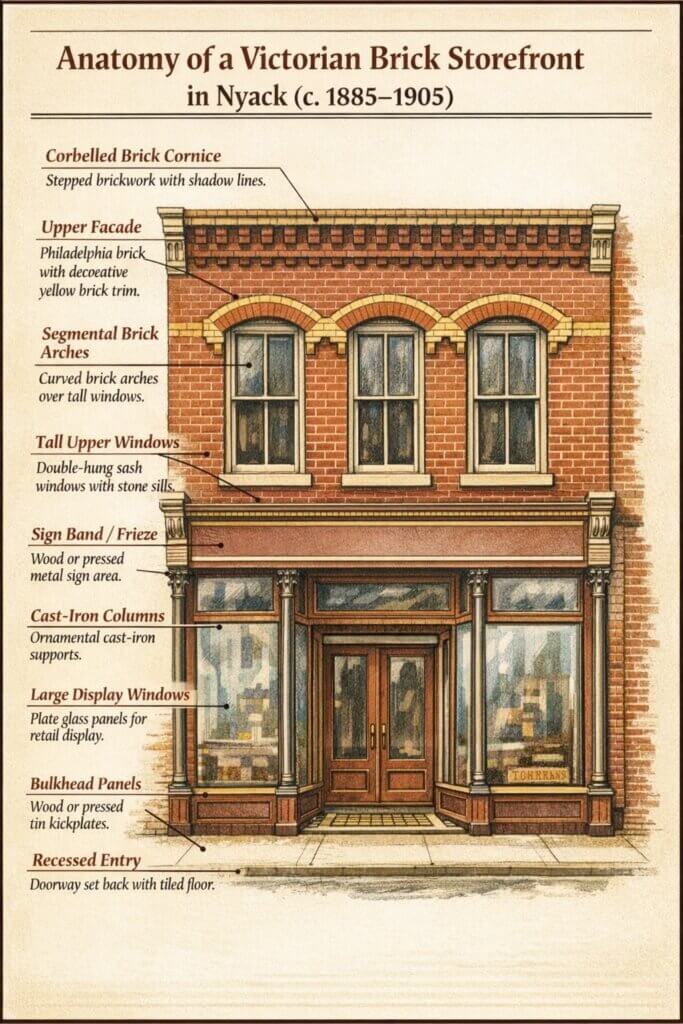

Aesthetic Brick Frontages in the Gilded Age

The Gilded Age transformed American streetscapes, and brick became one of its most visible materials. Advances in kiln technology and mass production changed how brick was used. Builders moved beyond plain, utilitarian walls. They adopted aesthetic brick frontages that advertised prosperity, craftsmanship, and modern taste.

Hard-fired face brick replaced earlier soft local brick. These bricks were sharply cut and uniform in color. Corbelled cornices, patterned bonds, molded arches, and polychrome accents followed. Entire blocks became sculptural compositions. Main streets gained new visual richness.

Nyack embraced this trend with enthusiasm. Working buildings relied on durable Haverstraw common brick, produced just upriver. Commercial façades increasingly featured Philadelphia face brick, prized for its deep red color and refined finish. Architects such as the Emery Brothers and masons like John Magee often combined the two. Philadelphia brick appeared on street-facing elevations. Haverstraw brick was used on sides and rear walls. The result was economical yet visually striking.

This combination still defines many buildings on Main Street and Broadway. Many storefronts are now painted. Some original brick cornices have been replaced with wood. Even so, the underlying Gilded Age aesthetic remains visible. Buildings such as the Harison & Dalley Department Store, Schmitt’s Ice Cream Parlor, and several Emery-designed commercial blocks clearly embody this approach.

Philadelphia Brick in Nyack

Philadelphia brick—a deep, uniform red face brick made from iron-rich clays—was the prestige material of the Gilded Age. Builders used it on front façades for its smooth finish, crisp edges, and decorative bonding patterns, while more utilitarian Haverstraw brick formed the side and rear walls. Its refined appearance gave Main Street storefronts a polished, urban character, even though many are now painted and several original brick cornices have been replaced with wood.

Why Nyack Used It

- Signaled refinement and modern taste

- Withstood Hudson River weather better than local brick

- Created cleaner, more elegant storefronts and façades

How to Recognize It Today

- Originally a rich, even red rather than mottled

- Narrow, precise mortar joints

- Smooth, uniform surface

- Typically used only on the street-facing elevation

Examples appear along Main Street near Broadway, on commercial buildings throughout North and South Broadway, and on some Queen Anne and Italianate homes built between 1880 and 1910.

Stone Foundations and Façades in the Gilded Age

While brick reshaped Nyack’s commercial streets, stone followed a parallel revival. Long before the Gilded Age, the village relied on local red sandstone for early foundations, walls, and boundary markers quarried from nearby outcrops. By the mid-19th century, however, wood-frame construction proved faster and cheaper. As a result, sandstone largely disappeared from everyday use.

That pattern changed with the arrival of the Gilded Age. Improved quarrying methods, expanded rail transport, and shifting architectural tastes brought stone back into favor. No longer merely structural, stone reemerged as a statement material.

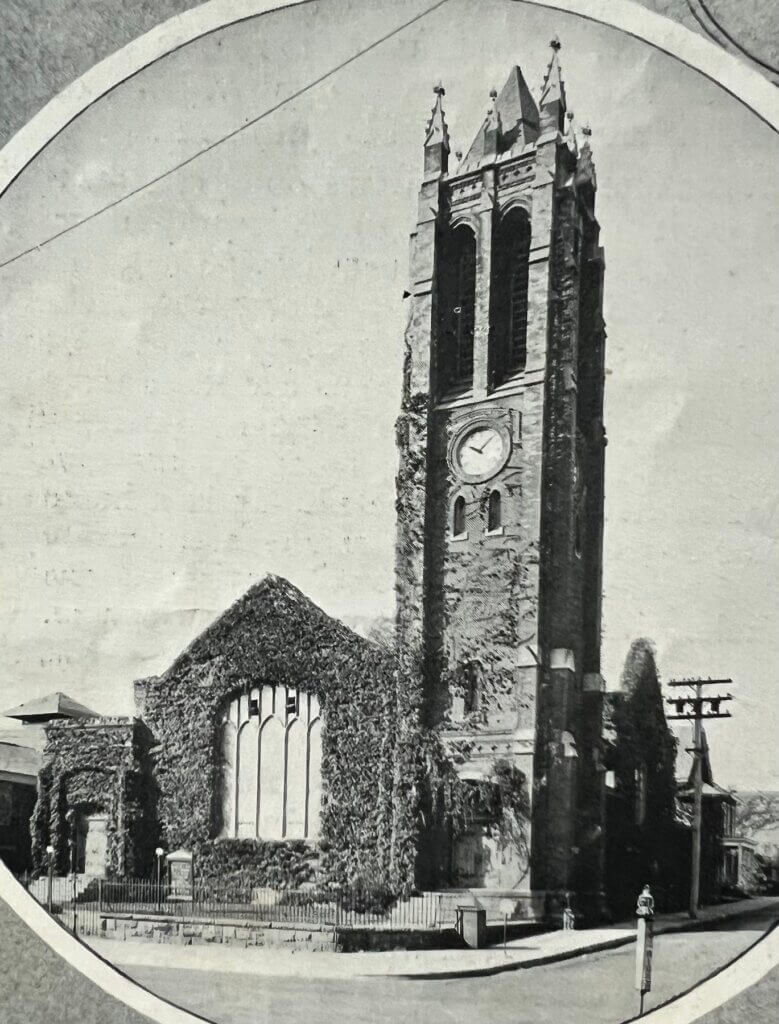

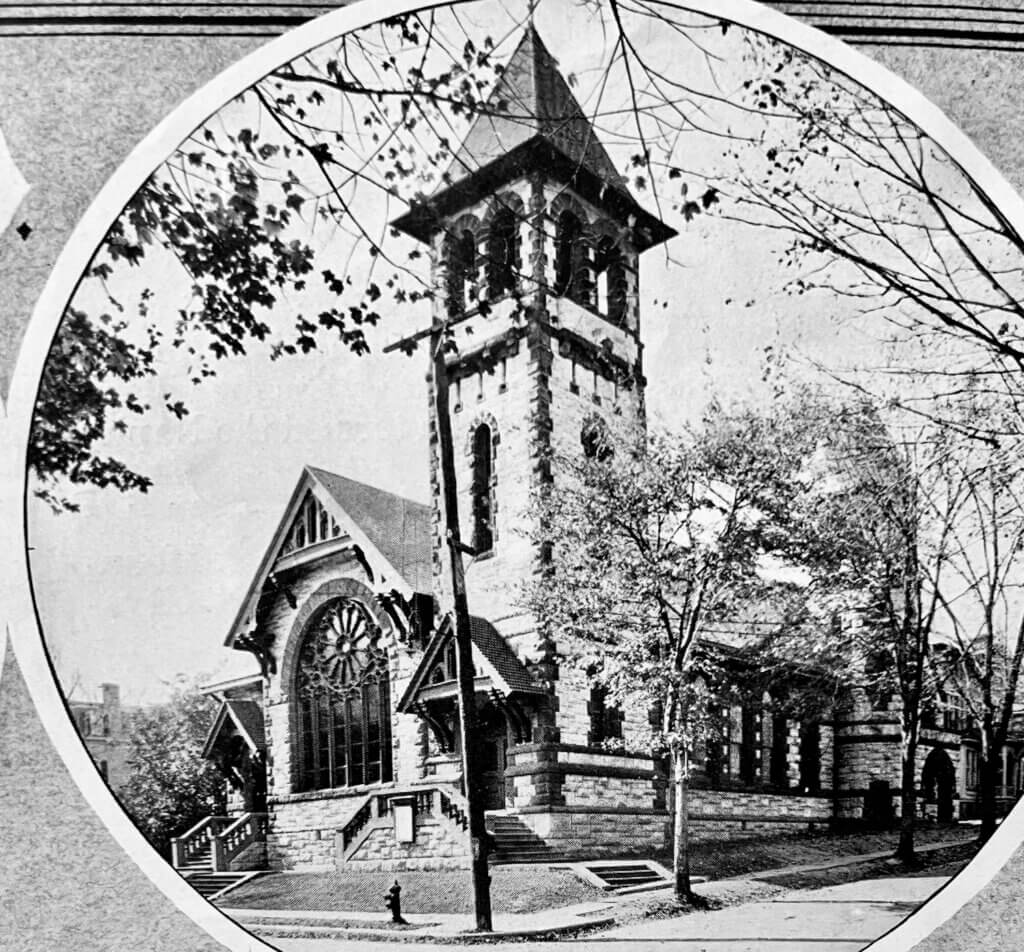

The revival appeared first in churches and institutional buildings. Influenced by the Romanesque Revival, builders favored massive stone walls, arched entrances, and heavy towers. Rough-faced limestone, granite, and trap rock created weight and shadow. Nyack followed national trends closely.

Bell Memorial Chapel under construction. Could Magee be one of the people shown at left?

Popularity of Building in Stone in Nyack

One of the clearest local expressions was the Bell Memorial Chapel. Among Magee’s most striking works, it used thick Indiana stone walls and a towered profile to project permanence and spiritual gravity. Even when brick formed the bulk of a structure, stone often defined façades, entrances, and key architectural elements.

From public buildings, the use of stone spread to residential architecture. Many of Nyack’s late-19th-century Queen Anne and Shingle Style homes feature stone first stories. Porches frequently rest on stone piers. Foundations rise high enough to read as architectural features rather than mere supports.

These stone bases served both visual and social purposes. They grounded houses visually and distinguished upscale residences from surrounding wood-frame streets. Magee’s work on the Howard Van Buren House exemplifies this approach. Muscular stone lower floors support a more elaborate upper story. The effect conveyed wealth, craftsmanship, and modern taste in Gilded Age Nyack.

John Magee (1856–1933)

Behind this transformation stood a builder whose career bridged continents and industries. Magee arrived in America at age five when his parents emigrated from Armagh, Ireland, and settled in Piermont. He attended public school and later the private school of Professor Welsh. He learned brick masonry in New York City.

By the mid-1870s, Magee’s work extended well beyond the Hudson Valley. In 1875 he joined major industrial projects, including the Carnegie Steel plant in Braddock, Pennsylvania. The plant helped revolutionize steelmaking through the Bessemer process. That same year, Magee traveled west to California and later to the Isthmus of Panama. There, he worked on bridge construction tied to improvements along the Panama Railroad.

Magee circa at his house with , from L to R, daughter Violet, Violet and child, and fur daughters in a buggy on Fifth Avenue

After years of travel, Magee returned to the region to put down roots. He came back to Piermont in 1880 and married Elizabeth Kennedy. Together they raised ten children—three sons followed by seven daughters. Two sons, John Jr. and William, entered the masonry trade. James pursued law and later became an assistant district attorney in New York City. Elizabeth died in 1920.

As his professional reputation grew, Magee’s presence in Nyack became permanent. Around 1890 he built his own home at 21 Fifth Avenue, at the corner of Marion Street. A horse barn across Marion Street burned in 1905, killing two of Magee’s horses. It was one of the few documented setbacks in his long career.

Despite the demands of his business, Magee remained socially active. He took sleigh trips to Tuxedo and traveled by stagecoach to regional events. In 1933, while visiting a daughter in Far Rockaway, Long Island, Magee died at age 75.

Selected Magee-Built Churches and Memorials

- Reformed Church expansion (1900), South Broadway and Burd Street, Nyack

- Bell Memorial Chapel (1899), Clinton and Hillside Avenues, Nyack; Indiana stone walls, tower; demolished for the Thruway

- Church of the Transformation (1897), South Broadway, Tarrytown

- Oak Hill Cemetery office building (1907), Nyack; rough-hewn stone first floor

- St. Paul’s Methodist Church (begun 1893), now Iglesia Las Mision A/D, Nyack; Emery design, rusticated stone with brownstone trim

Magee-Built Commercial Buildings

- Doersch Shoe Factory (1895), Depot Place area, Nyack; two-story brick factory, 30′ × 85′. (Demolished during Aniline Dye factory explosion in 1919.)

- Tuttle Shoe Factory addition (1900), Mill Street, Nyack; brick addition, 30′ × 70′. (Office building today.)

- Schmitt’s Ice Cream Parlor (1896), 84 Main Street, Nyack; three-story brick building with patterned Philadelphia-brick façade. (Current home ofThe Breakfast and Burger Club.)

- Cosgriff Trap Rock Company (1897), Rockland Lake Landing; multiple industrial structures, including a primary building measuring 50′ × 100′ (Demolished)

- Harison & Dalley Department Store (1894), Main Street, Nyack; 50′ × 145′ building later converted into Woolworth’s (much altered in a 1915 fire)

Selected Magee Residential Buildings

- John Magee House (1890), 21 Fifth Avenue, Nyack

- Howard Van Buren House (1899), South Broadway, Nyack

- Tunis Dutcher House (1894), South Broadway and Smith Avenue, Nyack

- Matthew DeBaun House (1894), 24 Division Street, Nyack

- Sherman House (1897), foot of Clinton Avenue, Nyack

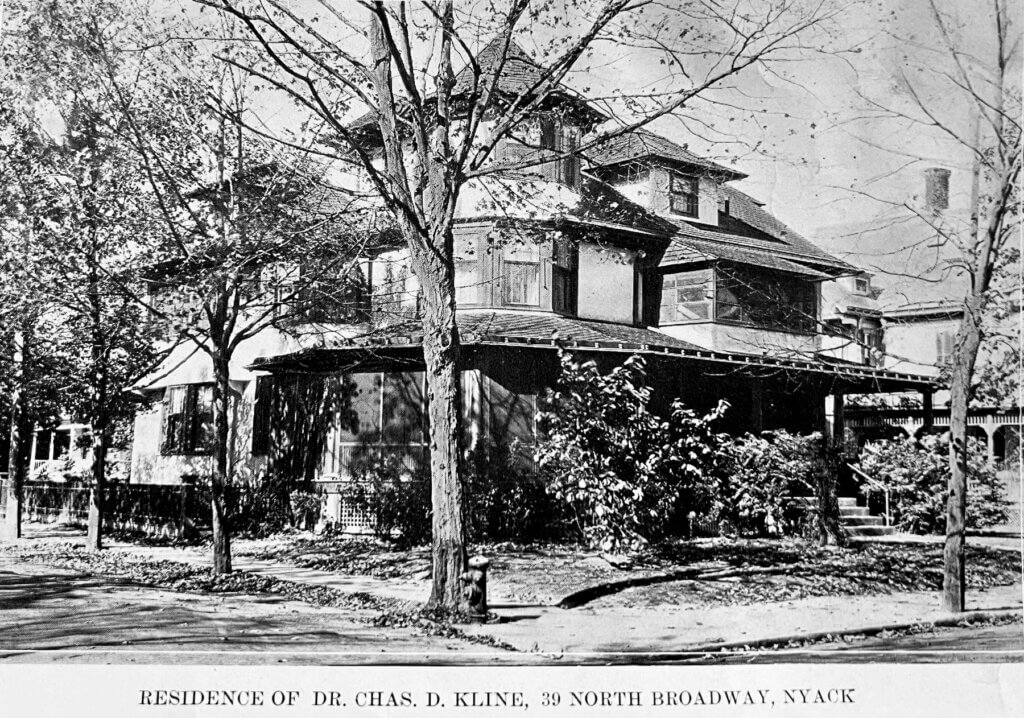

- Dr. Charles Kline residence (1899), 66 North Broadway, Nyack

- Davies House (Belle Crest) (1906), North Broadway, Upper Nyack

- Tuxedo Park residences, multiple locations

John Magee and Gilded Age Nyack

John Magee greatly influenced Gilded Age Nyack, constructing churches, storefronts, and distinctive homes that define the area’s character. His work helped turn Nyack from a river village into an established town, and his legacy is still evident downtown and along South Broadway.

About the Author

Michael Hays is a local historian, writer, and preservation advocate. Since 2017, he has written the Nyack People & Places column for Nyack News & Views, exploring the history, architecture, and personalities of Nyack and the lower Hudson Valley. He serves as Historian for the Village of Upper Nyack and has held leadership roles with the Historical Society of the Nyacks and the Edward Hopper House Museum & Study Center. He is the creator of the Barons of Broadway and the upcoming Nyack History A to Z series.

Editor’s note: This article is sponsored by Sun River Health and Ellis Sotheby’s International Realty. Sun River Health is a network of 43 Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHCs) providing primary, dental, pediatric, OB-GYN, and behavioral health care to over 245,000 patients annually. Ellis Sotheby’s International Realty is the lower Hudson Valley’s Leader in Luxury. Located in the charming Hudson River village of Nyack, approximately 22 miles from New York City. Our agents are passionate about listing and selling extraordinary properties in the Lower Hudson Valley, including Rockland and Orange Counties, New York.