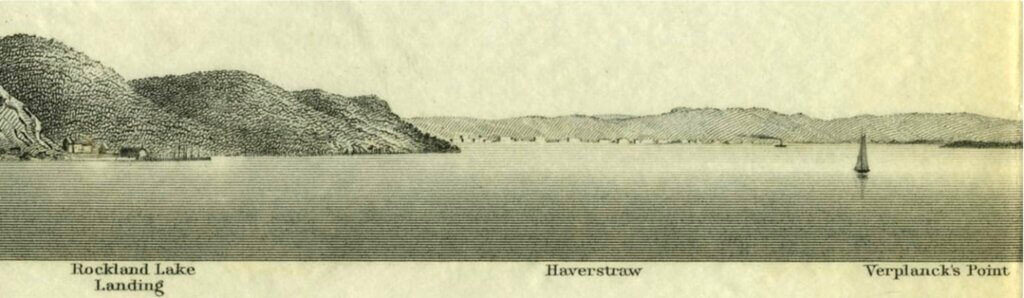

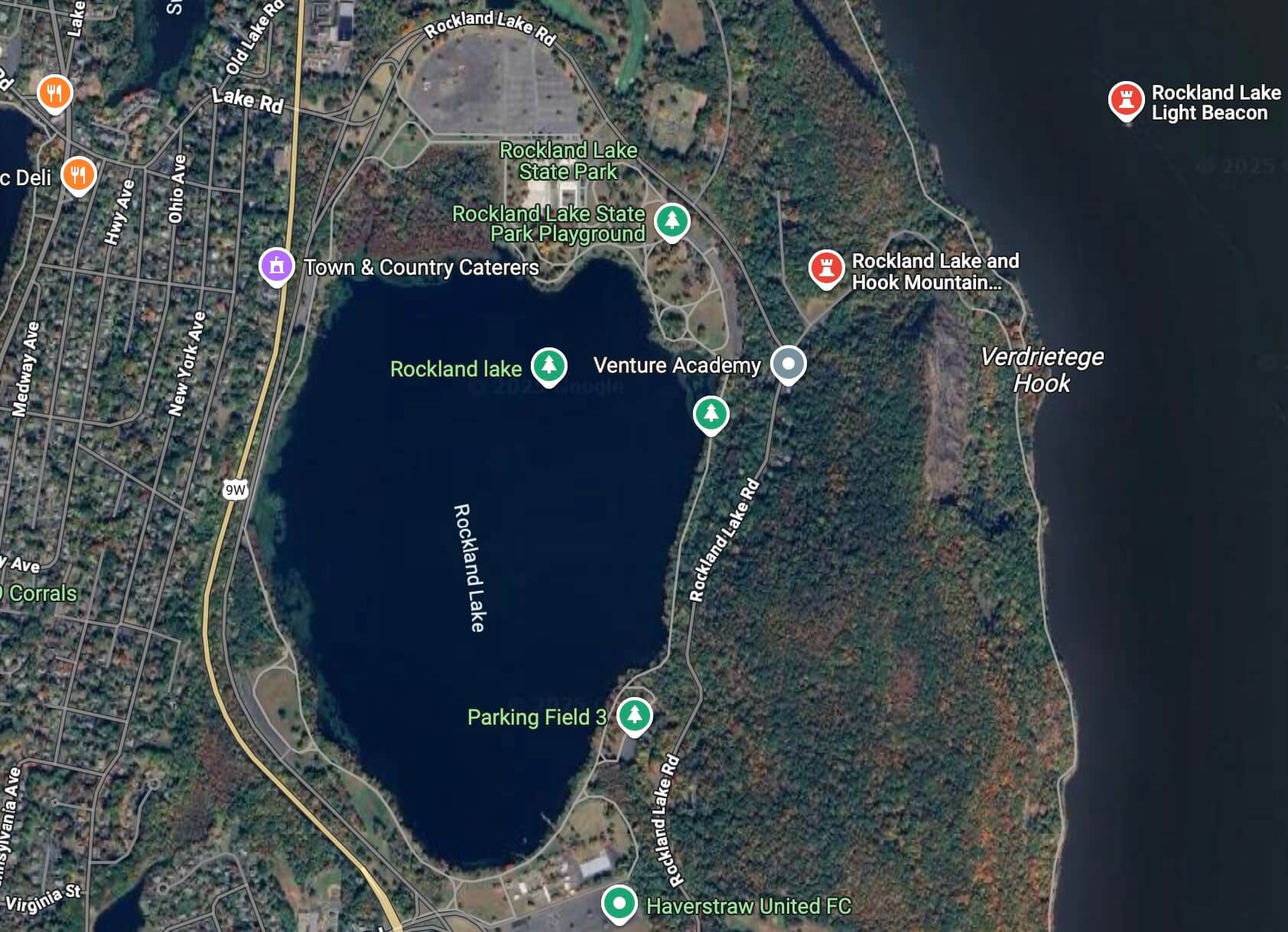

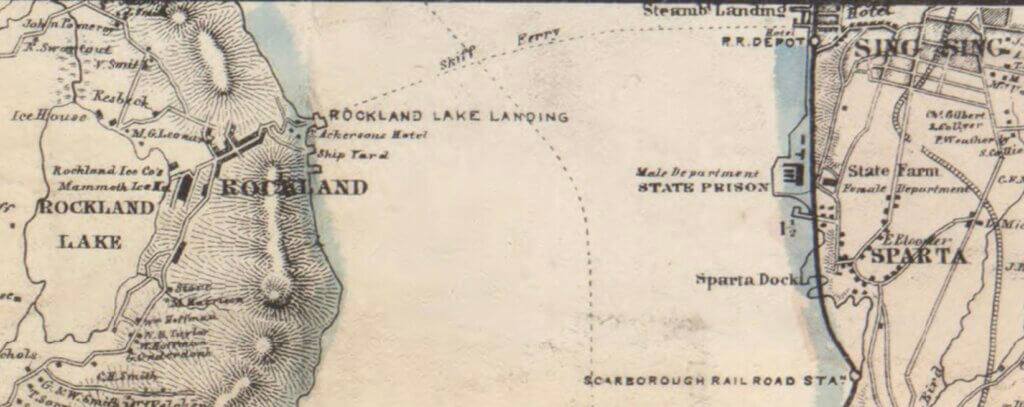

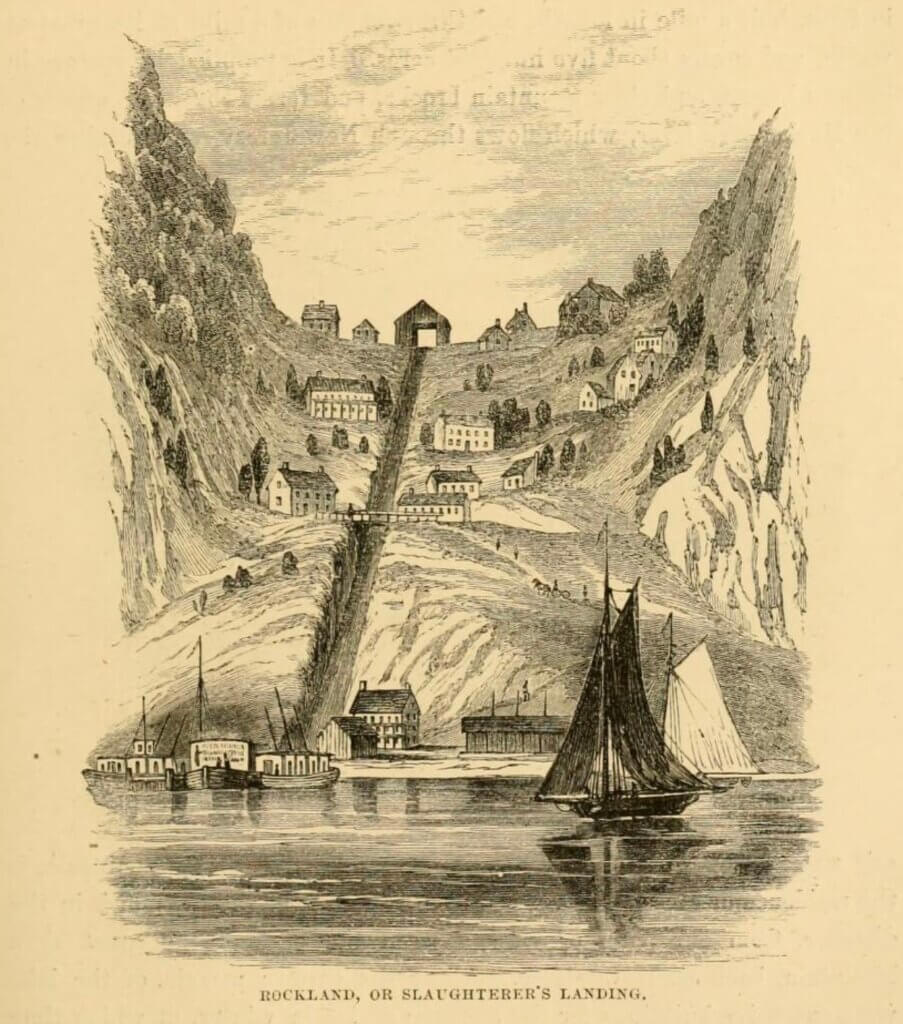

Rockland Landing lies just 1.5 miles from Nyack—but without road access, it feels far more remote. Once a quiet colonial ferry point, it grew into a booming industrial dock in the mid-1800s, home to Knickerbocker Ice Company barges and the Foss & Concklin Trap Rock Company.

By the late 19th century, the landing boasted a hotel, shipyard, general store, and a gravity-powered railway that carried ice down the mountain. Nearby, dynamite blasted the Palisades to create trap rock used in construction. Barges hauling stone and ice to New York City lined the pier. In 1894, a lighthouse was added to guide steamers past a hazardous oyster bed—but like the Leaning Tower of Pisa, it began tilting soon after construction.

Though the ice and stone trades eventually faded, the site experienced a brief rebirth in the 1930s and ’40s as a WPA-supported amusement park with a beach, dance hall, and dock for day liners. A brutal nor’easter in 1950 destroyed it all.

Few today realize how busy—and how crucial—this quiet spot once was.

In Part 1, we explore how Rockland Landing evolved from an Indigenous fishing site and Revolutionary War ferry to one of the Hudson’s most surprising industrial success stories.

The Haver stroos

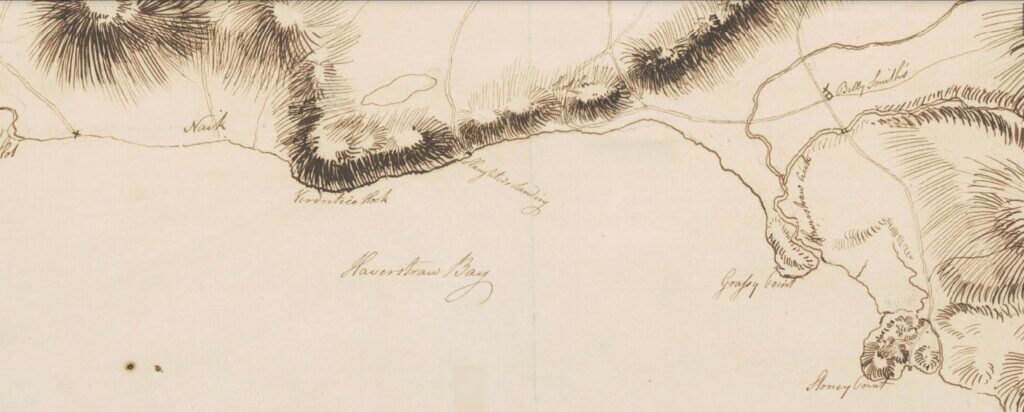

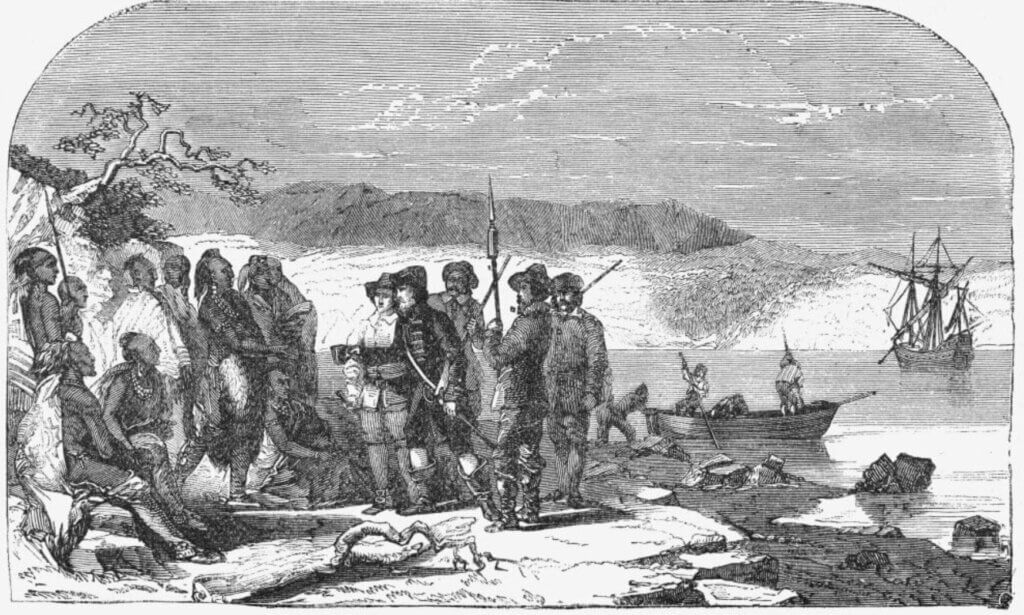

The story of Rockland Landing begins with the region’s Indigenous people, although little is known about them. They likely used the site seasonally for fishing and oystering. As the Palisades curve west near Haverstraw to form the High Tor ridge, they created a natural territorial boundary between two groups: the Tappans and the Rumachenank (later referred to by the Dutch as the Haver stroos). The name “Havers troo,” a Dutch word for wild sea oats, described the plants that grew in the shallow western parts of Haverstraw Bay. It’s likely the Haver stroos used the landing regularly.

Dutch colonist David de Vries described their clothing in a 1650 journal:

“A coat of beaver skins, over the body, with fur in the winter, and outside in the summer… They wear coats of turkey feathers, which they know how to put together. They make shoes and stockings of deerskins and braid corn husks together for shoes.”

David de Vries, 1650

Henry Hudson Encounters the Haverstroos

In 1609, English navigator Henry Hudson and his crew sailed the Dutch ship Half Moon up the Hudson River in search of a Northwest Passage. On their return, they anchored in Haverstraw Bay—the river’s widest point—on September 23. Haver stroos from the surrounding hills boarded the ship to trade oysters and beans. A tragic incident occurred when a sailor shot and killed a man who tried to steal from the ship, an act that strained future relations with local Indigenous communities.

Hudson’s voyage claimed the Hudson Valley for the Dutch and opened the door to trading, colonization, and centuries of conflict.

The Quaspeck Land Purchase of 1694

Indigenous people called Rockland Lake Quaspeck, though the meaning of the word has been lost. Early settlers referred to it simply as “The Pond.” The name Rockland Lake wasn’t adopted until the 19th century.

On May 30, 1694, William Welch and Jarvis Marshall purchased 5,000 acres called Quaspeck from seven Indigenous men, including one named Copphichonock. The tract stretched from Hook Mountain to High Tor, and from the Hudson River west to the Hackensack River valley. Governor Benjamin Fletcher confirmed the patent under William and Mary’s reign. The annual rent: one peppercorn for five years, then 20 shillings per year.

The new owners quickly subdivided and sold the land. By 1700, four different parties had surveyed the property, although it’s unclear whether any of them settled there. In 1729, Tunis Snedeker of Long Island acquired 2,500 acres of the eastern portion. That land was later subdivided and eventually came under the control of Hon. Abraham B. Conger, namesake of today’s village, Congers.

The “Clove”

Despite frequent changes in ownership, the 1700 landholders agreed to build a road through the “Clove” to the Hudson River. The word comes not from the spice but from the Dutch kloove, meaning a cleft or gash in the earth. In Rockland County, the term “clove” referred to mountain passes—such as Short Clove in Haverstraw and Long Clove in Congers. The road to the landing eventually became known as “Trough Hollow,” a name that faded over time.

John Slaughter’s Ferry & the Revolutionary War

In 1711, John Slaughter purchased land near Rockland Lake and established a ferry landing that came to bear his name. Like Snedeker’s Landing to the north and Snedens and the Sloat (Piermont) Landings to the south, Slaughter’s Ferry served both passengers and freight. A range of small craft—including flat-bottomed boats and small sail-powered vessels called periaguars—served the river here.

Just a few miles north, Kings Ferry (linking Stony Point and Verplanck) became the most strategically important crossing during the Revolutionary War. The Continental Army, George Washington, and even the captured spy Major John André all crossed there.

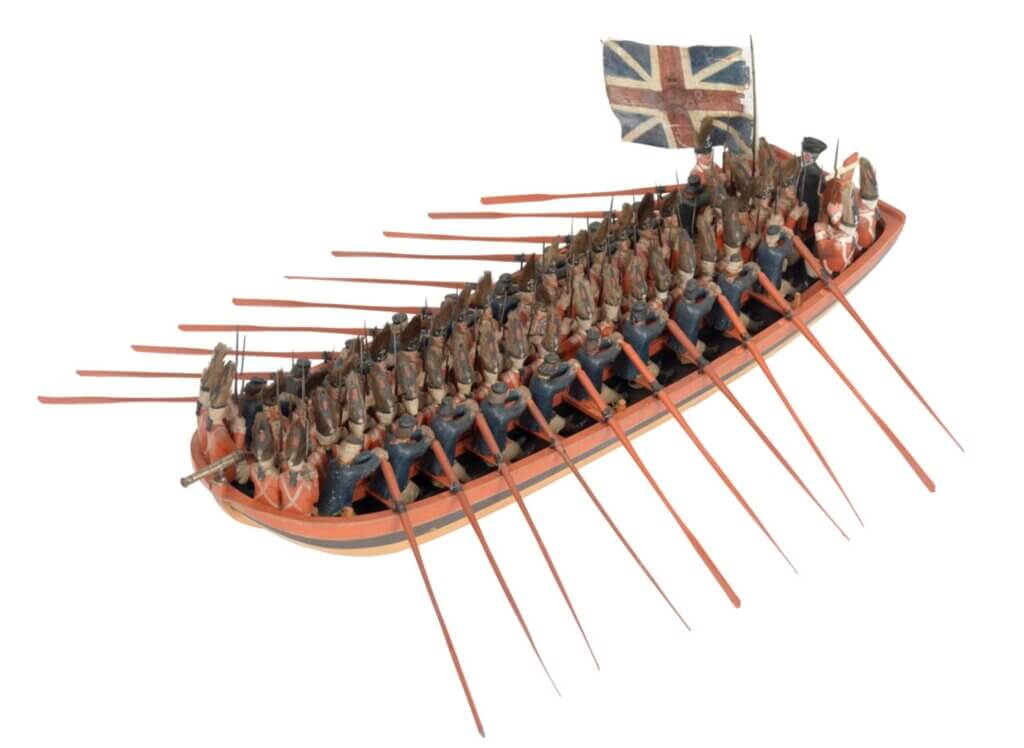

British Raiding Parties Use Rockland Landing

British raiding parties frequently landed at Slaughter’s Ferry. In one case, British marines marched around Rockland Lake. On the west side of the lake, farmer Garett Meyers watched the British fleet from his hillside farm. When they landed at nightfall, he tried to escape and light the warning beacon on Hook Mountain. But after hearing the approach of marching troops, he hid in a tree. A Tory neighbor later betrayed him. British soldiers assaulted Meyers’ wife and captured him, sending him to Sugar House Prison in New York City, where he remained until the war’s end.

In another raid, British troops advanced inland to Strawtown Road and ambushed a small patriot group led by Major John Smith of the Nyack Shore Militia. Smith escaped on horseback, pursued by British soldiers on stolen horses. The chase passed Cedar Grove Church and continued up Long Clove Road before the British gave up.

Not every patriot was safe from suspicion. Thomas Snedeker, of the founding family of the Quaspeck Patent, had his farm looted by British soldiers—guided by local Tories. They took livestock and captured him but soon released him. When Snedeker later sought compensation from British authorities, his actions sparked accusations of Loyalist sympathies. After the war, his house was confiscated and given to Jacobus Swartwout, who dammed the Kill von Beast to form a lake. A.B. Conger later lived in the same house.

Expansion of Rockland Lake Landing

By the 1830s, the Barmore and Felter Ice Company had put Rockland Lake on the map for its pure ice. The landing became critical for transporting this “clean gold” to the city.

In 1839, Nathaniel Barmore and Moses Leonard, now leading the Knickerbocker Ice Company, built a hotel near the landing. Captain Isaac Cook served as the first manager, followed by Thomas Akerson, who ran it until his death in 1883.

A.P. Stephens, a Nyack resident and congressman, built a store at the landing in 1840. It was later managed by L.F. Fitch. In 1850, Francis Powley constructed a marine railway to build and repair Knickerbocker boats. It passed through the hands of John and Henry Perry before being run by Nyack shipbuilder George Dickey. After Dickey’s death, the shipyard closed.

Moses Leonard and the Ice Trade

Moses Leonard was one of the driving forces behind Rockland Lake’s ice industry. A Connecticut native, he came to Valley Cottage as a young teacher, married into the Barmore family, and acquired land at the lake’s north end. There, the first icehouse was built.

Leonard was no ordinary businessman. While running the ice company, he also served on Brooklyn’s city council and became one of the first aldermen in San Francisco. Even so, he found time to market Rockland Lake ice—carrying samples in a handkerchief to major hotels in Manhattan.

The Ice Train: An Engineering Marvel

Transporting ice from lake to river over the mountain required ingenuity. The Knickerbocker Ice Company built a steam-powered (later electric) rail cart system from the ice houses on the lake to the village. Horses pulled the carts across the village’s flatter sections to the top of an incline. From there, a gravity-powered railway with dual tracks allowed full carts to descend while empties returned uphill. Brakes at the base slowed the loads before transfer to barges.

The “ice train” worked throughout the company’s life. At its peak, Knickerbocker could store 100,000 tons of ice and operated 60 barges capable of moving 40,000 tons. In New York City, 1,000 horses delivered ice from riverfront storage sheds to homes and businesses.

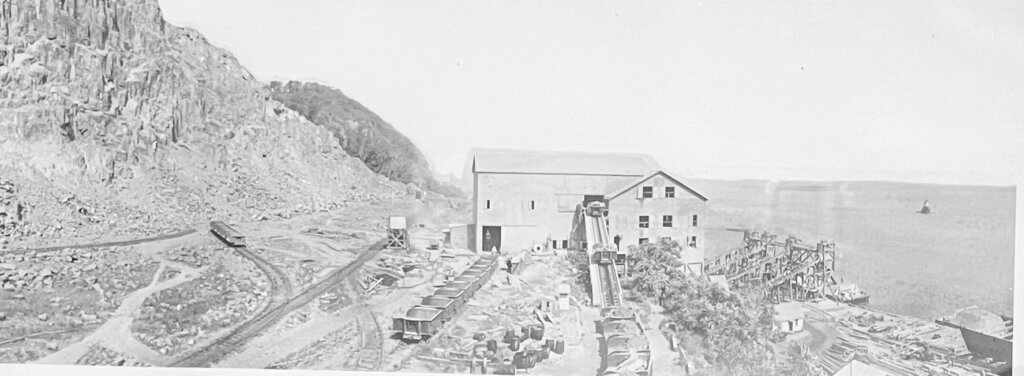

Crushing Stone: The Rise of the Trap Rock Industry

After 1870, New York’s explosive growth created demand for strong stone. Trap rock, a dense igneous material, became essential for roads, railroads, and foundations. The Hudson River offered the perfect shipping route.

When ice harvesting ended each spring, many workers shifted to quarrying. In 1872, John Mansfield installed a crusher at the landing to break dynamited chunks into small stones. M.M. Miranda later bought it. By 1884, four crushers ran from April to December, filling up to 90 barges a year and employing dozens of men.

Dramatic Changes Afoot

As the 19th century wore on, Rockland Lake Landing thrived, propelled by ice and stone. But new technologies—and rising complaints about dust and blasting—would soon force change. In the next chapter, this once-booming site enters its final transformation, from industrial powerhouse to riverside park.

Mike Hays lived in the Nyacks for 38-years. He worked for McGraw-Hill Education in New York City for many years. Hays serves as President of the Historical Society of the Nyacks, Vice-President of the Edward Hopper House Museum & Study Center, and Upper Nyack Historian. Married to Bernie Richey, he enjoys cycling and winters in Florida. You can follow him on Instagram as UpperNyackMike.

Editor’s note: This article is sponsored by Sun River Health and Ellis Sotheby’s International Realty. Sun River Health is a network of 43 Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHCs) providing primary, dental, pediatric, OB-GYN, and behavioral health care to over 245,000 patients annually. Ellis Sotheby’s International Realty is the lower Hudson Valley’s Leader in Luxury. Located in the charming Hudson River village of Nyack, approximately 22 miles from New York City. Our agents are passionate about listing and selling extraordinary properties in the Lower Hudson Valley, including Rockland and Orange Counties, New York.