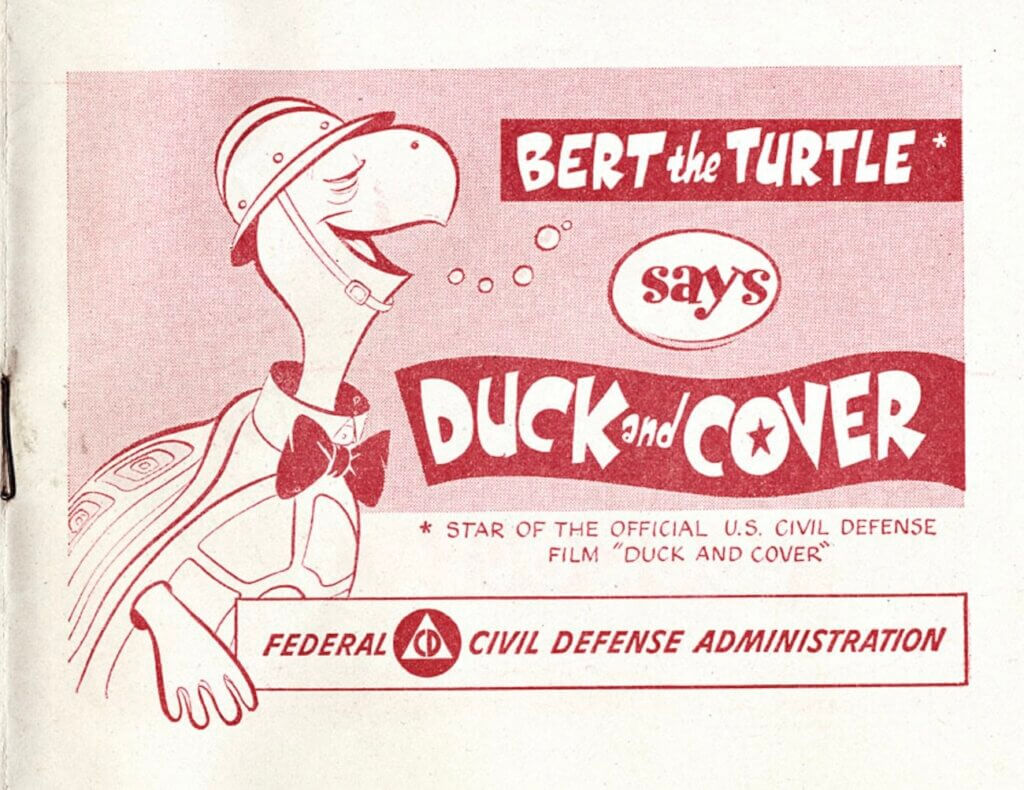

In 1955 during the Cold War—when schools ran civil-defense “duck-and-cover” drills that had kids drop under desks and families weighed backyard fallout shelters—the U.S. Army activated a Nike surface-to-air missile site on Clausland Mountain above Nyack.

Long used as a lookout—from Revolutionary-War beacons to a WWII aircraft-spotting tower—the summit now held radar and command posts linked to a launch area in Orangeburg, first with conventional Ajax missiles and soon with nuclear-armed Hercules, part of the air-defense ring around New York City. It wasn’t secret; most residents accepted the idea of nuclear missiles in the suburbs. Missiles even appeared at local fairs and church bazaars.

Mount Nebo

Clausland Mountain is a chain of Palisades hilltops between Piermont and South Nyack. Its highest point—nearly 700 feet—is Mount Nebo at the southern end, overlooking Rockland Cemetery and Piermont. The biblical name recalls the mountain where Moses viewed the Promised Land. Local maps use the name inconsistently, and its origin remains unclear. Trees block most of the view except in winter. Thin soils and exposed rock made the area poor farmland, and historic maps show no nearby homes.

You reach Mount Nebo via Tweed Boulevard, named for Boss Tweed. In the early 1870s, Tweed’s associates pitched the idea of a grand hotel atop Hook Mountain, served by a new road from New Jersey. Land speculation and political corruption sank the project, but parts of the road survived. The terrain posed real engineering challenges; the route wasn’t fully paved until after World War II and remains a steep one-way road at its southern end.

Watchfires, Beacons, and an Observatory

Rendering of a Revolutionary War soldier observing a watchfire.

Mount Nebo holds Rockland County’s only original mountaintop Memorial Day watchfire, a modern tradition begun by Vietnam veterans. The fires echo a Revolutionary-War system of beacon posts—pyramids of logs fired at night and smoked by day—that relayed alarms along the Hudson Highlands. Documented sites ran from Bear Mountain to Mount Beacon; on the Palisades, High Tor appears in local records as a signal point. Clausland (Mount Nebo) has the sightlines and likely participated, though firm primary documentation hasn’t surfaced. Today’s Memorial Day watchfires on Clausland and other peaks intentionally honor that earlier warning network.

The summit has long drawn observers. In 1897, the federal government erected a survey tower there to map the Hudson River, and local young people favored the spot for moonlit walks.

“The Germans Are Coming”: The WWII Watchtower

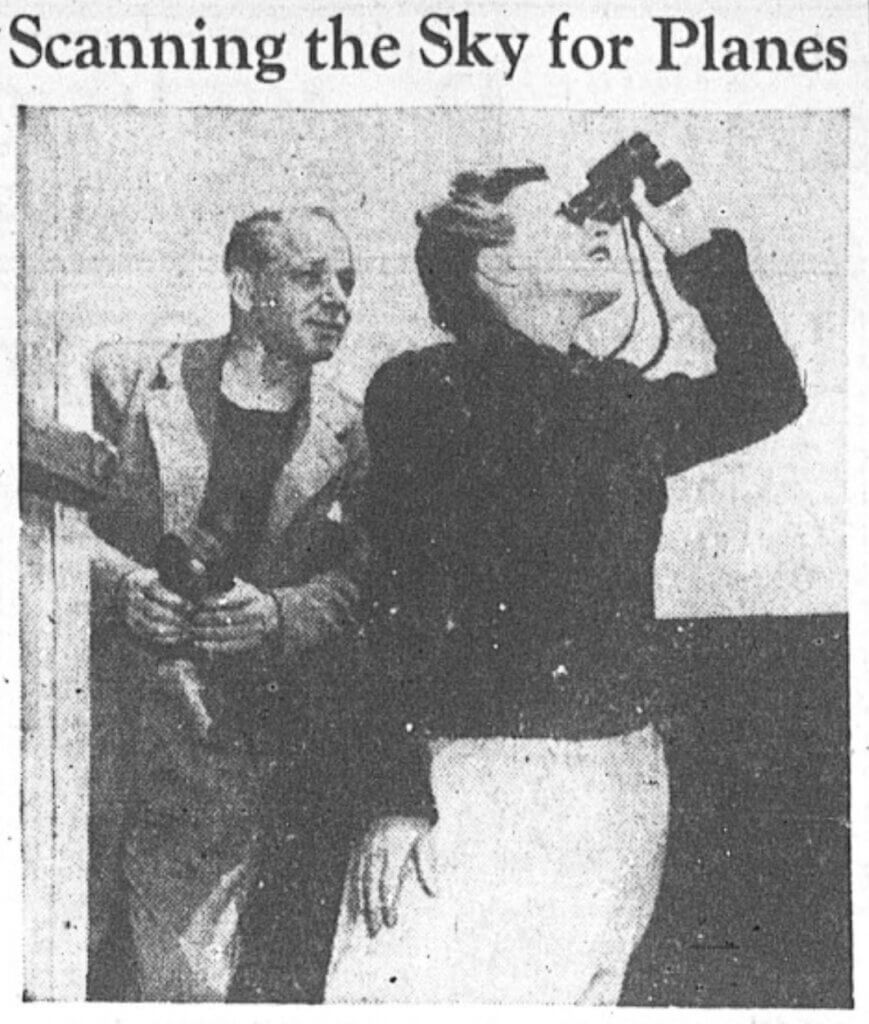

Before Pearl Harbor, the county highway department built a 25-foot aircraft-observation tower on Mount Nebo’s bedrock to spot German planes. An eight-sided enclosure topped the structure, reached by steep steps and, for a time, a ladder through a trap door. Crews trimmed trees to open the view. Full-time use would begin only in an emergency.

That emergency arrived with Pearl Harbor. The tower went to 24/7 duty. Ninety volunteers signed up immediately, followed by another hundred. The first was Helen Bryant, an Englishwoman. Volunteers included a dentist, a banker, journalists (among them Hal Petit, editor of the New York Times Sunday Magazine), Upper Nyack attorney Orville Mann and his brother, World War I veterans, and even Helen Hayes and Charles MacArthur, who posed atop the tower. One spotter worked the 12–3 a.m. shift and still caught the 7:16 a.m. train to the city. Entire families sometimes stood watch together.

Life on the Tower

Wind battered Mount Nebo and the tower even more so. Windows leaked in the rain. At first there was no phone. Volunteers kept a car idling beside the tower; when a plane appeared, a spotter scrambled down, jumped in, and drove 0.3 miles to a nearby house to use the phone. When the homeowners were away, they left the door unlocked.

Snow complicated everything. Relief observers couldn’t always reach the summit; cars failed on the hill; volunteers trudged through drifts. A pot-bellied stove and a telephone eventually made duty more bearable. Signs inside read, “They shall not pass unreported” and “Spot. Identify. Report.” The work was tedious, with few diversions. “The only recreation up there is shining the windows,” one observer joked. Smoking was forbidden.

Almost nothing threatening appeared—no wrecks, no U-boats on the Hudson, no German aircraft. When neighbors once reported flickering lights, police discovered the “signal” came from the tower’s light switching on as someone climbed the steps—or when a parked car on the nearby lovers’ lane pulled too close.

Orangetown’s Nike Missile Base

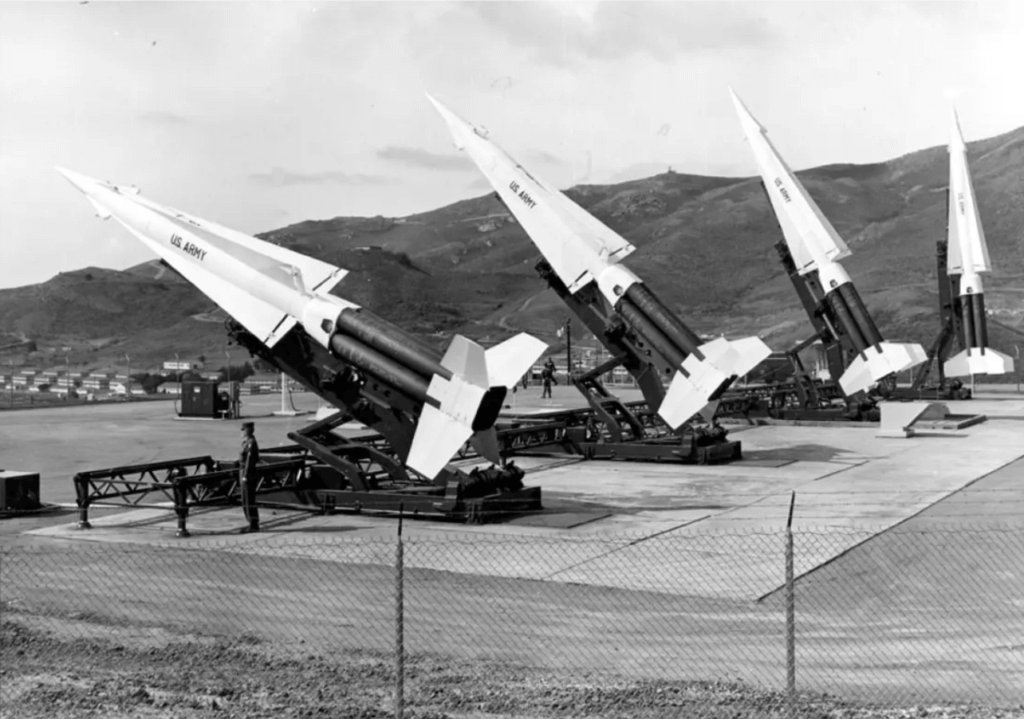

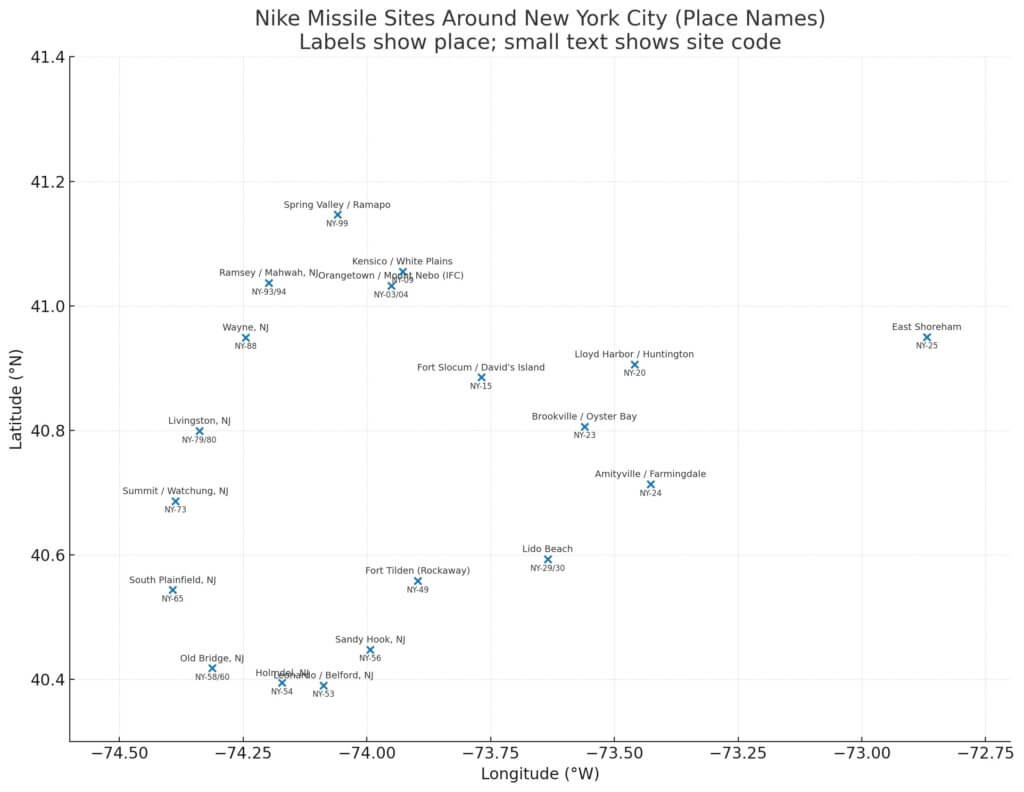

The Army activated the Nike program in 1955 to intercept nuclear-armed Soviet bombers. Cities were ringed with missile batteries sited far enough away that spent rocket casings wouldn’t rain down on dense neighborhoods.

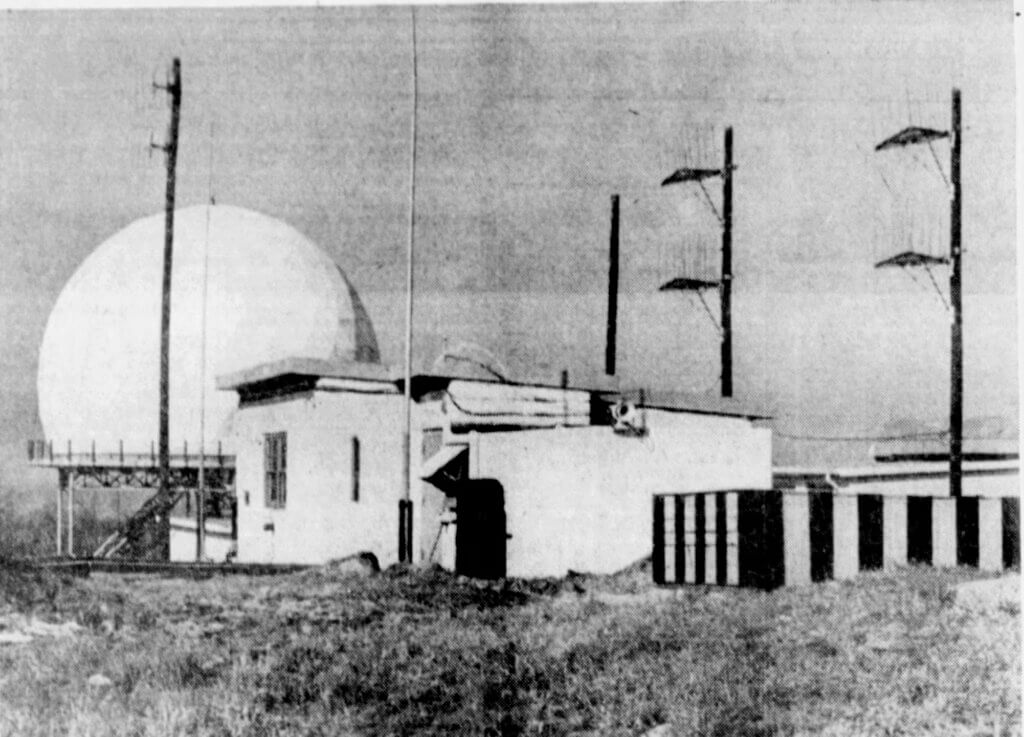

The Army already controlled Mount Nebo from WWII, and it made an ideal radar and command post. On the 15-acre summit, engineers built a command center and a large spherical radome—its round foundation still remains. The missile-launch site sat below the mountain at the northwest corner of the Palisades Interstate Parkway and Route 303. Crews kept the missiles in underground silos until launch.

A third site in Spring Valley housed soldiers. By 1965 those grounds served as auxiliary elementary-school classrooms and later became a yeshiva.

From Ajax to Hercules

The Orangetown complex went operational in 1955 with 60 Nike Ajax missiles carrying conventional warheads. The Army soon replaced them with larger Nike Hercules missiles with nuclear warheads, which had roughly a 75-mile range and could reach about 200,000 feet—high enough to destroy a squadron of bombers in one burst.

SALT and Shutdown

Intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) made bomber attacks increasingly obsolete. After the 1972 SALT I agreement, the Army closed Nike bases nationwide. By 1974 the Orangetown complex was mothballed. Crews sealed the silos and shut down the mountaintop radar. No missile ever launched from Orangetown—or from any other U.S. Nike site in combat. The program’s worst tragedy occurred in 1958 at Leonardo, New Jersey, where an explosion killed ten soldiers.

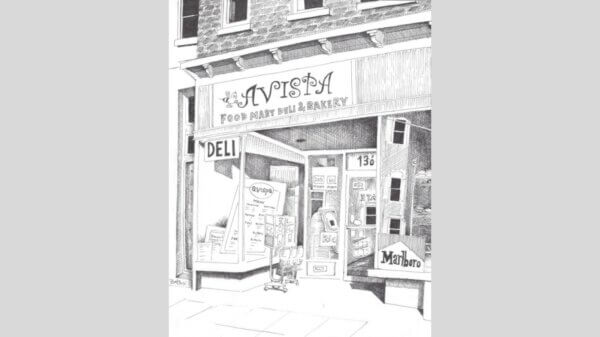

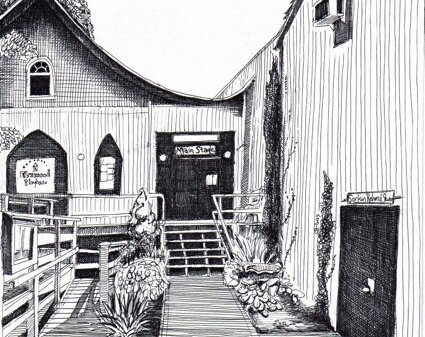

Photos of some of the remaining buildings at the old Nike radar site.

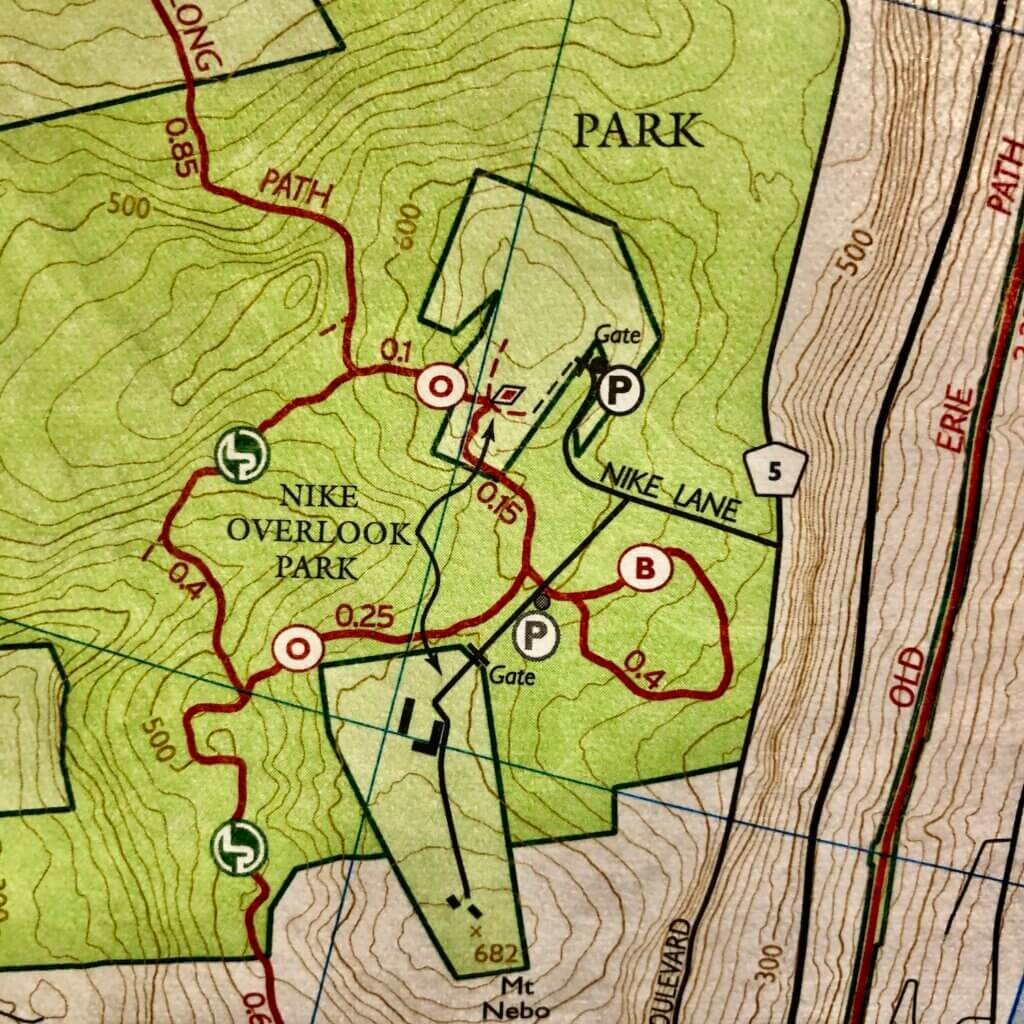

Nike Missile Overlook Park

In 1976, Orangetown purchased the Mount Nebo radar-tracking site for $10,000 and added a few improvements, including a pavilion. Plans for a pool went nowhere. In 1995, the Upper Grandview Association proposed preserving the buildings as a Cold War Museum, but the idea stalled.

Today hikers know the park best. An orange-blazed trail links to the blue-blazed Long Path, which runs from the George Washington Bridge to the Catskills. Rusted structures and concrete foundations—including the base of the old radome—remain as graffiti-marked reminders of a tense era when missile alerts, nuclear fear, emergency sirens, and school “duck-and-cover” drills shaped daily life.

Mike Hays lived in the Nyacks for 38-years. He worked for McGraw-Hill Education in New York City for many years. Hays serves as Treasurer of the Historical Society of the Nyacks, Vice-President of the Edward Hopper House Museum & Study Center, and Upper Nyack Historian. Married to Bernie Richey, he enjoys cycling and winters in Florida. He has written the Nyack People & Places column since 2017. You can follow him on Instagram as UpperNyackMike.

Editor’s note: This article is sponsored by Sun River Health and Ellis Sotheby’s International Realty. Sun River Health is a network of 43 Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHCs) providing primary, dental, pediatric, OB-GYN, and behavioral health care to over 245,000 patients annually. Ellis Sotheby’s International Realty is the lower Hudson Valley’s Leader in Luxury. Located in the charming Hudson River village of Nyack, approximately 22 miles from New York City. Our agents are passionate about listing and selling extraordinary properties in the Lower Hudson Valley, including Rockland and Orange Counties, New York.