In 1826, the audacious notion of a village of just two hundred souls embarking on the construction of a steamboat raised eyebrows. Yet, the completion of the Nyack Turnpike opened up new horizons, ushering fresh opportunities for shipping goods from Nyack to New York City. However, the formidable steamboats originating from Albany and other ports, en route to New York, routinely bypassed Nyack.

Enterprising visionaries from Nyack, including John Green and the Smith brothers, mustered their resources to form the Nyack Steamboat Association, armed with a capital infusion of $10,850. Their resolve was clear: they would construct a pioneering steamboat, a decision that would leave an indelible mark on Nyack’s history. This vessel, initially christened the “Nyack” and then the “Orange”, and later humorously dubbed the “Pot Cheese” for its unconventional appearance, would reshape Nyack’s destiny.

Constructing the “Pot Cheese”

The Orange came to life under the skilled craftsmanship of Harry Gesner, who set up shop at the foot of Clinton Avenue in South Nyack. Gesner, renowned for his boatbuilding expertise, had previously crafted the Advance in 1815, the first substantial center-board boat in the United States. While smaller than Fulton’s inaugural steamboat, the Orange boasted dimensions of 75 feet in length and 22 feet in beam width. Paddlewheels on both sides were powered by an engine manufactured in West Point, and its design allowed for conversion into a coasting schooner in case of engine failure. The Orange had a dining room and a bar.

Far from a paragon of elegance, resembling more a ferry than a sleek schooner, it garnered the jesting moniker, “Pot Cheese.” Furthermore, the Orange’s lack of speed led to it being facetiously referred to as the “Flying Dutchman.”

Immediate Triumph

Launched in 1828 as Nyack’s first locally built steamboat, the Orange enjoyed instant success. Carriages and wagons streamed into Nyack via the newly minted turnpike, forming lengthy queues on Main Street to load goods onto the Orange, at times stretching as far as Cedar or Franklin Streets.

Each item transported on the Orange incurred a separate fee. Adults paid 25 cents for passage, while children paid half that amount. The cost for a horse and wagon was $1.50, with varying fees for horses, cows, sheep, and hogs. Even lambs and calves had their own reduced fare. Building materials, such as timber, planks, bricks, shingles, paint, lime, and coal, were not exempt from fees. This bustling activity at the docks spurred the growth of businesses catering to both workers and travelers.

At the time, steamboats primarily relied on wood as fuel, resulting in a towering wall of wood lining Main Street. Loading the boat with wood for the downstream journey was a laborious task, taking approximately 7-8 hours. However, the docks thrived with newfound activity.

Navigating the Waters

John White Jr. assumed the role of the first captain at a monthly salary of $110, augmented by profits from the onboard bar and restaurant. He also provided board for the crew, excluding the engineer. Raymond Felter, hailing from Rockland Lake, served as the pilot, while Isaac P. Smith took up the mantle of engineer.

The published schedule dictated departure from Nyack at 4 p.m. for New York City, with a return journey the following day, commencing at 11 a.m. Stops included Sneden’s Landing in Palisades, Closter Dock, and Huyler’s Landing in Alpine, NJ, before arriving in Manhattan. Favorable tides and winds facilitated a brisk three-hour trip downstream. The upstream voyage posed greater challenges, often extending to a full day’s journey. On occasion, the Orange took on more freight than it could safely accommodate, necessitating the use of one or more sloops towed behind it, further slowing its pace.

Interestingly, passengers welcomed the arduous journey as an opportunity for social interaction. In this close-knit community, deck conversations and cabin knitting sessions were commonplace. Dutch remained the lingua franca among passengers until around 1846, adding to the unique charm of local steamboat journeys.

Competition on the Horizon

Piermont and Haverstraw could not stand idly by while Nyack enjoyed the lion’s share of shipping and associated businesses. Businesspeople from Tappan formed the Orangetown Point Steamboat Company to rival the Orange. The Rockland, a larger and faster steamboat than the Orange, plied a route from Orangetown Point to New York City. Subsequently, stops in Haverstraw and Upper Nyack were added, conspicuously avoiding Nyack’s dock.

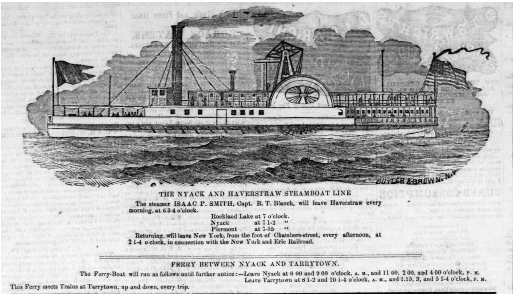

Captain Isaac P. Smith

Isaac Smith, one of the four Smith brothers instrumental in initiating and expanding Nyack’s steamboat enterprise, assumed the captaincy of the Orange at the youthful age of 30, a few years after its launch. His lack of prior experience in captaining a steamboat did not deter him from confronting the newer, speedier boats emanating from Piermont and Haverstraw. Remarkably, despite piloting the plodding “Pot Cheese,” Smith often emerged victorious in these rivalries.

Smith’s prowess extended beyond competition; he possessed a practical, inventive mindset. His innovations included altering the Orange’s lines by adding a false bow to streamline the boat—an unprecedented feat that yielded remarkable results.

Subsequently, Smith captained the Arrow, the Armenia, and in 1850, built his own steamer, the Isaac P. Smith, which he went on to captain for a period. In 1852, he supported the establishment of a foundry in Nyack for the manufacture of steamboat machinery. Smith embodied the legacy of steamboat captains along the Hudson River, epitomizing the spirit of competition and camaraderie that defined Nyack’s burgeoning steamboat industry.

Emergence of a New Challenger

In the mid-1830s, a novel steamboat company based in New York City introduced the Warren. This vessel sailed from De Noyelle’s dock at Haverstraw three days a week, making stops at Waldberg Landing, Slaughter’s Landing, Nyack, Sneden’s Landing, Closter Dock, Huyler’s Landing, and Hammond Street, returning the following day.

The End of an Era

The Orange’s days were numbered as new entrants to the steamboat scene emerged. The Smith brothers—Isaac P., David D., Abram, and Tunis—constructed the sleek Arrow in 1840, which graced the Hudson for 26 years, surviving two fires in Nyack but succumbing to a burst flue in New York City, resulting in loss of life.

The “Pot Cheese” demonstrated that steamboat transportation could be a profitable venture, yielding dividends of $17,883. The Smith brothers’ gamble paid off, positioning Nyack as a prominent commercial hub in Rockland County. The affectionate nicknames bestowed upon it are a testament to the cherished place it held in the hearts of the Nyack community, a vessel that propelled this small village into a leading commercial position along the Hudson River.

Michael Hays is a 35-year resident of the Nyacks. Hays grew up the son of a professor and nurse in Champaign, Illinois. He has retired from a long career in educational publishing with Prentice-Hall and McGraw-Hill. Hays is an avid cyclist, amateur historian and photographer, gardener, and dog walker. He has enjoyed more years than he cares to count with his beautiful companion, Bernie Richey. You can follow him on Instagram as UpperNyackMike

Editor’s note: This article is sponsored by Sun River Health and Ellis Sotheby’s International Realty. Sun River Health is a network of 43 Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHCs) providing primary, dental, pediatric, OB-GYN, and behavioral health care to over 245,000 patients annually. Ellis Sotheby’s International Realty is the lower Hudson Valley’s Leader in Luxury. Located in the charming Hudson River village of Nyack, approximately 22 miles from New York City. Our agents are passionate about listing and selling extraordinary properties in the Lower Hudson Valley, including Rockland and Orange Counties, New York.