Hiking, Cycling, Coaching, & More

Recap

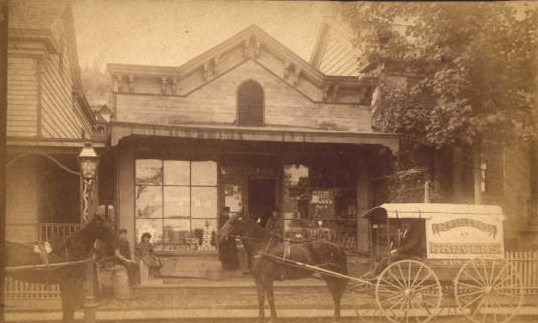

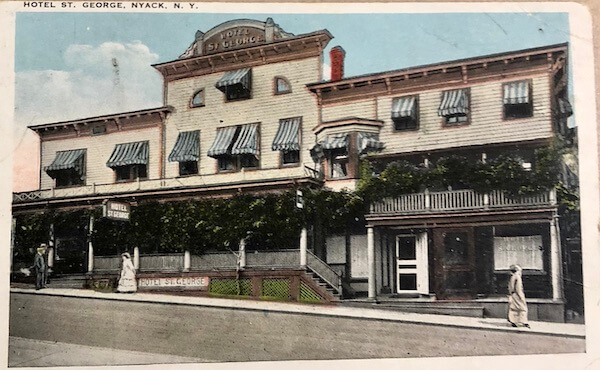

In the previous parts of this history of the St. George Hotel, we examined its origin, and learned about its founder, restauranteur George Bardin, and his famous meals. In this segment, we look at everyday life at the hotel with visits by hiking, cycling, and tally-ho coaching groups. Among countless visitors, life at the hotel included crime, a deranged guest, runaway horses, and segregation.

Walkers & Cyclists

Beyond being connoisseurs of fine dining, denizens of the Gilded Age were enthusiastic walkers, far surpassing today’s recommended 10,000 steps. In September 1899, three intrepid souls embarked on a challenge to trek from New York City to Nyack and back, completing the journey in 12 hours. They sought refuge at the St. George Hotel for the night. Likewise, in November 1890, eleven members of the NYC Fresh Air Club embarked on a rail journey to Haverstraw, trekking over the mountains to Nyack. The evening culminated in a grand feast at the St. George, followed by a train ride back to the city.

Cyclists, then as now, pedaled their way from the city to Nyack. The Montauk Wheelmen of Brooklyn charted a course to Nyack in late September 1892. Following a hearty luncheon at the St. George, they returned to the city via the Nyack Ferry, tracing a route along the east side of the Hudson. Meanwhile, John D. Rockefeller, Jr. and his companions would ferry to Nyack, cycle along River Road, and savor a repast at the St. George.

Tally-Ho Coaches

In the late 19th century, tally-ho coaches provided transportation for groups of travelers and sightseers pulled by a team of four to six horses. Tally-Ho coach excursions from New York City to Tuxedo, NY, with a stopover in Nyack, became a favorite pastime.. Orchestrated by Pierre Lorillard Jr.’s travel enterprise, the inaugural voyage set out in 1892. Departing from the Plaza Hotel in NYC, the coach reached Tarrytown for the 12:30 ferry, making a leisurely stop at the St. George for a lavish meal before continuing to Tuxedo at 2:30. Along the route, eight horse relays awaited in Yonkers, Dobbs Ferry, Nyack, Spring Valley, and Suffern. The return journey mirrored the path, with lunch again at the St. George. All in all, the 52-mile excursion spanned a mere 7 hours, inclusive of lunch breaks.

The Case of a Stolen Raincoat

In 1892, a young man sought a place to pen a letter at Moeller’s drugstore on South Broadway, later making his way to the St. George Hotel. Furnished with a desk, pen, and paper, he composed his missive. As diners departed that evening, they noticed a missing overcoat, replaced inconspicuously with an old hat. Proprietor Bardin suspected a fellow guest may have inadvertently taken it.

The following day, Bardin shared the tale with a local, Mr. Simonson. After leaving the St. George, Simonson visited the post office, retrieving a letter for his servant, its envelope marked with the St. George Hotel’s insignia. Upon inquiry, the servant revealed that the young man who had written the letter had visited her the previous day, identifying the exchanged hat as one worn by Howard Dann. An officer dispatched to NYC to apprehend him discovered that Dann had already departed on the midnight train to Buffalo. The resolution of this peculiar episode remains a mystery.

Runaway Horses

In 1893, a team and carriage were dispatched from a stable in South Nyack to retrieve a party late in the evening. As they waited in front of the hotel, the team suddenly bolted, hurtling down Piermont Avenue and colliding with a tree at the corner of Clinton Ave. It marked the second runaway incident of the day. Earlier, Oscar Luelich, a Main St. baker, had his horse and wagon break free, careening down Main St., then Broadway, causing a pastry-filled spectacle in front of the Reformed Church. The horse, dragging the lower half of the wagon, continued its rampage down Broadway until it toppled another baker’s wagon on South Broadway.

An Unhinged Guest

Shortly after Christmas in 1895, Mrs. James W. Clark, a scion of a wealthy NYC family and sister to a millionaire cracker magnate, suffered a mental breakdown in Nyack. Having undergone a medical procedure in the city, she sought solace in Nyack under the care of a family friend, Dr. D. L. Defendorf of Upper Nyack. During her stay, Mrs. Clark’s agitation escalated, prompting her to depart at 3 a.m.

Arriving at the St. George, she rang the bell and registered under the alias of Mrs. W.W. Brown of Newark. George Bardin assigned her room #7 on the second floor. The following morning, she descended for breakfast. Later, the housekeeper discovered newspaper wedged in the keyhole and beneath the door. Bardin, concerned for her well-being, conducted a cursory check for the scent of gas, ruling out any suicidal intentions. Satisfied, he resumed his duties. Hours later, news reached him that she had thrown open her window, blowing kisses and engaging with passersby on the street. Bardin hastened to her room, admonishing her for such behavior.

Sad Ending

By 3:30 p.m., Mrs. Clark had checked out of the St. George. On Broadway, she encountered two of Defendorf’s guests, who were seeking her. They persuaded her to return to Upper Nyack, but en route, she broke free, darting onto the grounds of the Nyack Country Club before darting house to house. Eventually, two deputized villagers apprehended her. When she brandished what was believed to be a pocketknife in front of the judge, she was subdued. Justice Bombard visited the Defendorf residence, inquiring whether they would take her back. They declined. Bombard ordered her confinement at the Village Hall jail. Her husband was telegraphed and expected to arrive the following day. Following a front-page debut, the resolution of Mrs. Clark’s troubled episode remains shrouded in mystery.

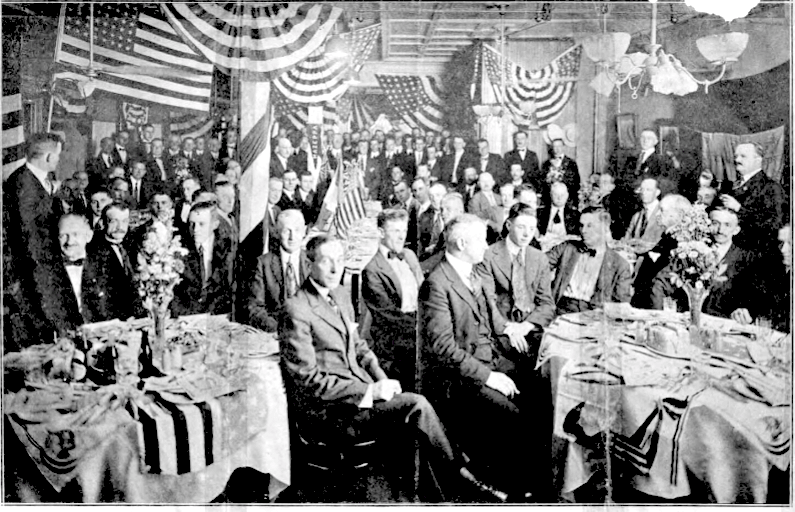

Jim Crow at the St. George

Before delving further, it’s crucial to acknowledge that, much like other Nyack restaurants of the era, the St. George was segregated. Leonard Cooke, former chairman of the Rockland County Human Rights Association, recounted how few restaurants welcomed black patrons. He noted, “the only time you could go into the St. George Hotel was to celebrate political victories, not to eat there.”

William Williams

However, the busboys, waiters, bellmen, and maids were predominantly African American. William Williams, a longstanding resident of Burd St., a World War I veteran, and a Nyack mail carrier, commenced his tenure at the St. George, following in his father’s footsteps. His initial task involved standing before the hotel, deftly sweeping away dust from arriving ladies and gentlemen, even those adorned in dusters. Williams recalled Sundays when a queue stretched back to the door, eager to gain entry. Over time, he transitioned to roles as a busboy, waiter, and bellboy.

He fostered connections with both George Barden and the subsequent owner, Felix Flieger, with whom he practiced German, a language he was studying in high school. By the time Fred Siemer assumed ownership of the St. George, Williams had taken on part-time work as a mail carrier. Often, during the lunch hour, he would serenade the St. George’s patrons with his musical talents, alternating between piano, saxophone, and clarinet. He was a regular performer, leading a five-piece orchestra known as the Utopians.

Acknowledging a Sad Legacy

Regrettably, William Williams, along with other black individuals, would have been unable to dine at the St. George without a formal invitation before the 1960s.

Michael Hays is a 35-year resident of the Nyacks. Hays grew up the son of a professor and nurse in Champaign, Illinois. He has retired from a long career in educational publishing with Prentice-Hall and McGraw-Hill. Hays is an avid cyclist, amateur historian and photographer, gardener, and dog walker. He has enjoyed more years than he cares to count with his beautiful companion, Bernie Richey. You can follow him on Instagram as UpperNyackMike