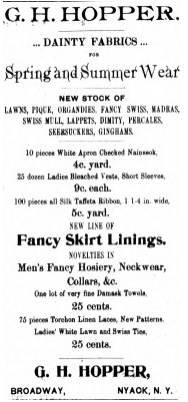

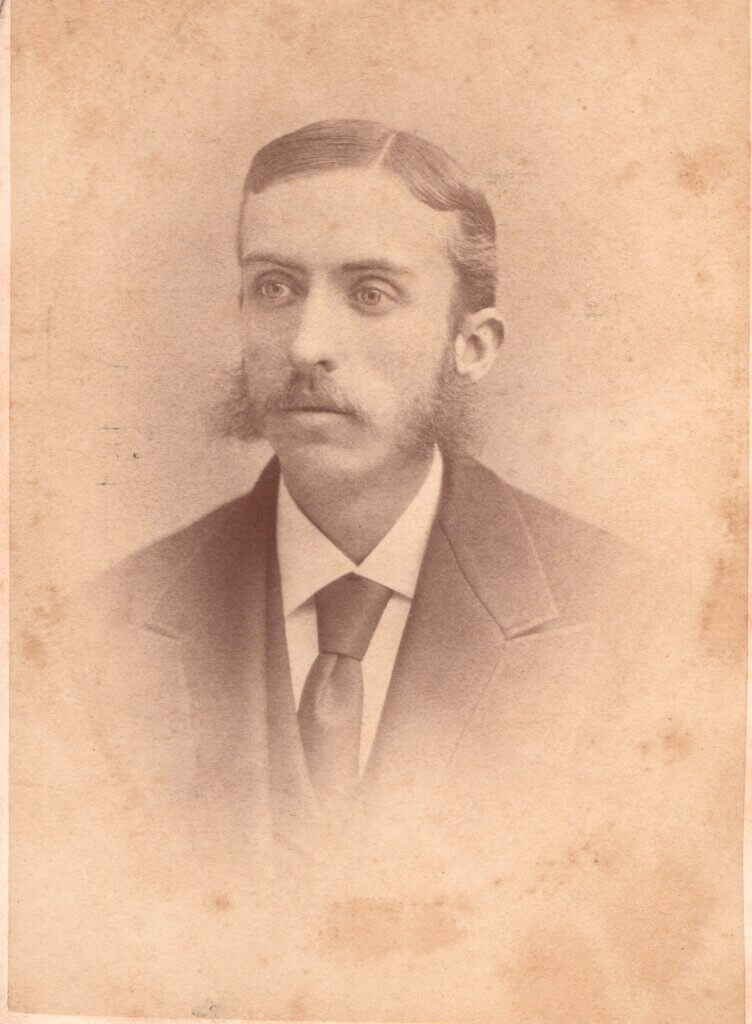

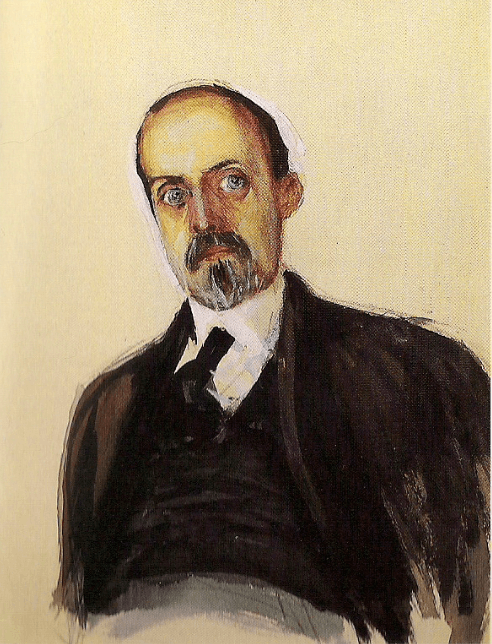

Garret Henry Hopper, who went by “G.H. Hopper” in business and “Garry” among friends, bore the appearance of an Edwardian intellectual or a European revolutionary. Surprisingly, he spent 15 years as an underwear salesman. In 1890, when Edward was eight years old, his father acquired a dry goods store on Broadway in Nyack. Just two years later, he purchased another store located at #10 South Broadway in the thriving four-story Commercial Building, which is now Grace‘s Thrift Shop.

In 1905, at the age of 53, Garret Hopper retired from business. At that time, his son Edward Hopper, then 23, had completed his art education and was preparing to journey to Paris for further artistic studies. Typically, a father might encourage his son to take over the family business, especially in the absence of other career prospects. Was there a conflict between father and son regarding Edward’s choice to pursue art? Did Garret’s business background influence Edward’s artistic career?

Garret Henry Hopper (1852-1913)

The obituary of Garret Hopper, featured on the front page of the Nyack Evening Journal, described him as a benevolent and amiable individual with a wide circle of friends. He served as a trustee of the Baptist Church, having adopted the Baptist faith after his marriage due to his wife’s family’s connection with the Nyack Baptist church. He participated in YMCA Committees and was involved with the Rockland County Historical & Forestry Society. A devoted reader himself, he imparted this love of reading to his son at an early age. Despite his active involvement in business and community, Garret exhibited a solitary inclination, a trait inherited by his son.

Hopper Family Lineage in America

The Hopper family, known as “Hoppen” until the fourth generation in America, immigrated to the United States in 1652. Andres Hoppen exemplified the classic Dutch trader, navigating the Hudson River on his sloop to engage in trade of various goods. After his demise, his widow remarried and relocated to a 300-acre farm near Saddle River. The prevalence of Hoppers in the area led to the nickname “Hoppertown” for what is now Ho-Ho-Kus, NJ.

Garret’s father, Christian Hopper, married Charity Blauvelt in 1850. They resided on a Saddle River farm. Garret, their only child, faced the loss of his father in a horse accident when he was just two years old. Following this tragedy, Garret and his mother, Charity Blauvelt Hopper, moved to New York City to live with Charity’s father, Andre Blauvelt. While in the city, the family immersed themselves in interests spanning music, art, and literature. This period in New York lasted until Andre’s passing in 1864.

The 1870 census provides a glimpse of Garret’s life, listing him as part of the household of Thomas and Catherine Hopper in Franklin, NJ. Both Garrett and Thomas are identified as farmers. Intriguingly, another Garret H. Hopper, aged 85, also resided in the same house.

After 1870, Garret relocated to Nyack, a rapidly expanding town rife with business opportunities. On March 26, 1879, he married Elizabeth Smith at her mother’s residence, which is now the Edward Hopper House Museum. During this time, he likely worked as a salesman. In the 1880 census, he is noted as being involved in the trade of gentlemen’s clothing. His occupation is similarly listed as a salesman on Edward’s 1882 birth certificate.

Ownership of a Dry Goods Store

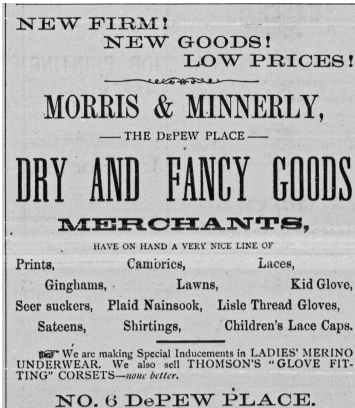

Garret’s in-laws, though not affluent, owned several rental properties on Marion Street. These relatives likely provided the capital necessary for Garret to acquire a dry goods business from Morris and Minnerly at the corner of Main and Broadway, a location they had occupied for just two years. The town boasted several dry goods stores during that era, with Cranston’s in the Onderdonk Block serving as a potential rival to Hopper’s enterprise.

What Is a Dry Good Store?

Early American “dry goods” stores initially encompassed establishments selling either groceries or fabric for clothing. By the 1880s, the emphasis on groceries had waned, and these stores now offered fabric for garments along with ready-to-wear undergarments for both genders, including corsets, umbrellas, gloves, and various accessories. Improved train accessibility to lower-priced New York City dry goods stores created competition for Nyack retailers, making customer service a pivotal aspect.

Garrett Hopper’s Expansion

In 1892, Hopper expanded his business by acquiring William O. Blauvelt’s 12-year-old dry goods store at #10 South Broadway. Prior to moving his business, Hopper extensively renovated the new location. Alterations included an expansion of the rear floor space by 21 x 15 feet, facilitated by the addition of a skylight to enhance lighting and ventilation.

Hopper diversified his inventory by incorporating toilet articles, perfumes, decorative soaps, photo frames, collar and cuff boxes, handkerchief boxes, and adorned crockery. During the Christmas season, he offered kid gloves for women and ties and scarves for men. Hopper gained recognition for his innovative store window designs and frequently advertised in local newspapers, particularly during his semiannual underwear sales. At one point, he experimented with a frequent-buyer program, where customers earned five-cent money orders for every $1.00 in sales, redeemable upon reaching a total of 20 orders for a $1.00 discount or cash.

Store hours extended from 10 AM into the evening, six days a week, making store management demanding. Hopper employed at least one long-standing staff member, Harry L. Tallman.

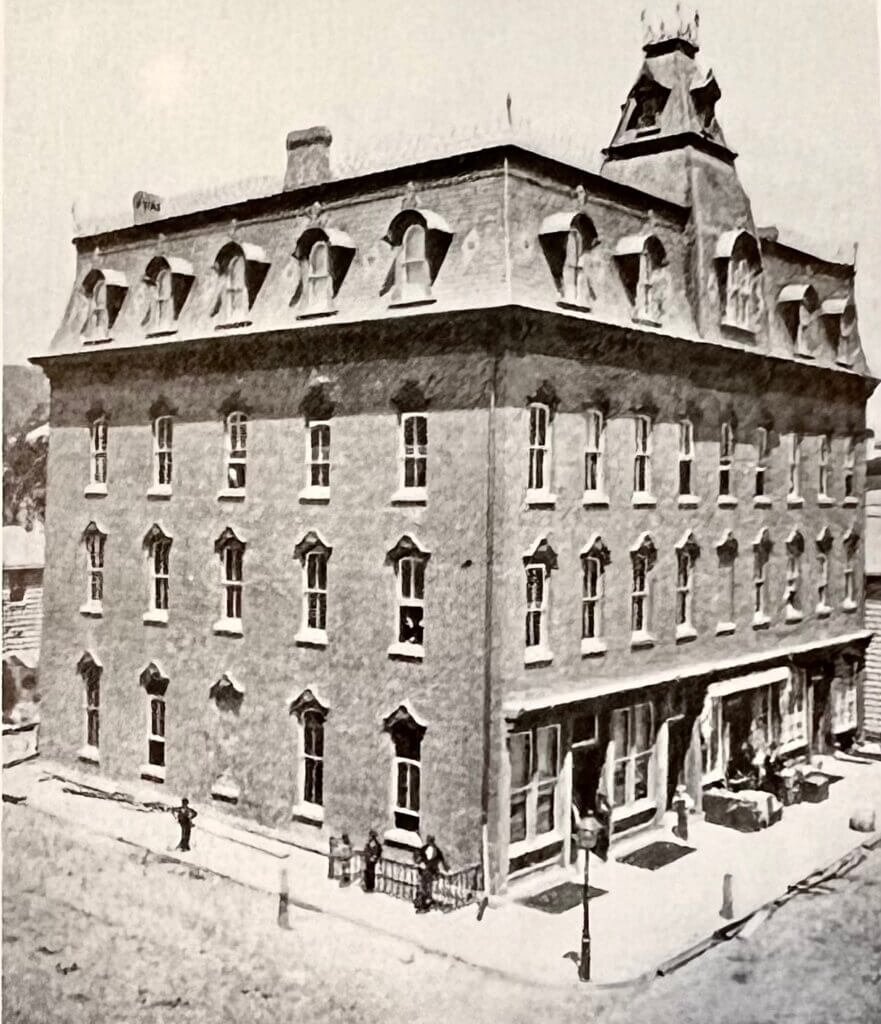

The Commercial Building

Before delving further, let’s take a moment to contemplate the building that housed Hopper’s business. The four-story Commercial Building, erected in 1873 during Nyack’s post-Civil War growth surge, achieved immediate success. The building was fully tenanted upon its opening, boasting a distinctive mansard roof crowned with ornamental grillwork and a cupola that dominated the downtown landscape.

The presence of a bank, Nyack Village Offices, a Police Court, legal and real estate offices, a furniture store, ice cream parlor, YMCA, local Odd Fellows and Masonic Lodges, and a “free reading room” made the Commercial Building a hub of activity. Many patrons traversed Hopper’s store on their way to the only bank in Nyack or to access various services and gatherings within the building. Its premier location rendered it ideal for specialty businesses.

The Enigma of the Commercial Building

Today, the former site of the Commercial Building is occupied by a two-story structure known as the Equity Building, adjacent to a six-floor building housing Pickwick books. The latter was once the Everett Hotel, constructed in 1907 and standing at a similar height to the Commercial Building. The transformation raises questions, with many speculating that a fire may have led to its downsizing.

However, historical records from July 22, 1927, indicate a radical renovation rather than a fire-related reduction. The building was scaled down by two floors, likely reflecting evolving fire safety regulations. The redesign introduced a new vestibule and stairway leading to 14 offices on the second floor. Changes were also evident in window placement and the exterior, now clad in imitation travertine over brick. Three storefronts faced Broadway, including Sheas’ drugstore on the corner.

Grace’s Thrift Shop: A Continuation of Legacy

Since 1969, Grace’s Thrift Shop, affiliated with Nyack’s Grace Episcopal Church, has occupied the former G.H. Hopper dry goods store location. Operated by volunteers who donate profits to community causes, the thrift shop remains a bustling establishment. Upon entering, the interior and shelving, particularly in the rear sections, evoke memories of the original dry goods store. The skylight installed in 1892 still illuminates the shop. The extension of the store behind the original four-story building enabled the installation of the skylight. With a touch of imagination, one can envision rows of neatly arranged items lining the shelves behind classic counters.

With all that in mind, we return to Edward Hopper and his father’s store.

Edward’s Amusing Summer Camp Letter

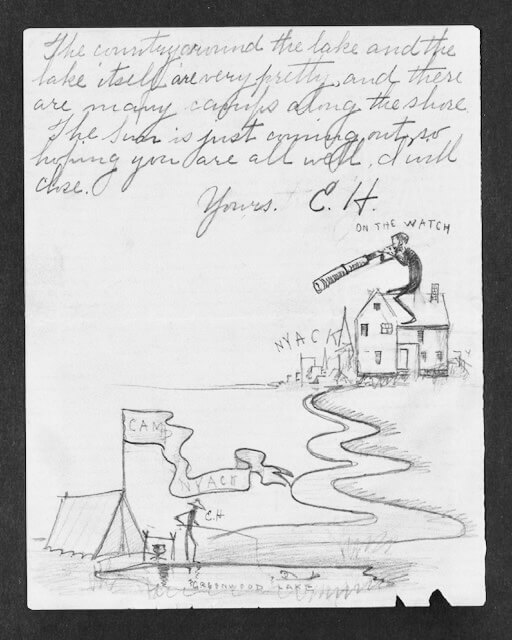

Following his initial year at art school, Edward Hopper returned home for the summer, setting up camp at Greenwood Lake, a seven-mile-long water body west of Suffern renowned among tourists and artists during the Gilded Age. In a cleverly executed sketch titled “Camp Nyack, Greenwood Lake,” he depicted his tent.

A letter dated July 26, 1990, addressed to his mother, offers insights into his summer escapades. He commented on rainy weather but shared that he was enjoying himself. Interestingly, he mentioned having “plenty of underwear” and humorously revealed wearing them beneath his clothes while in the lake.

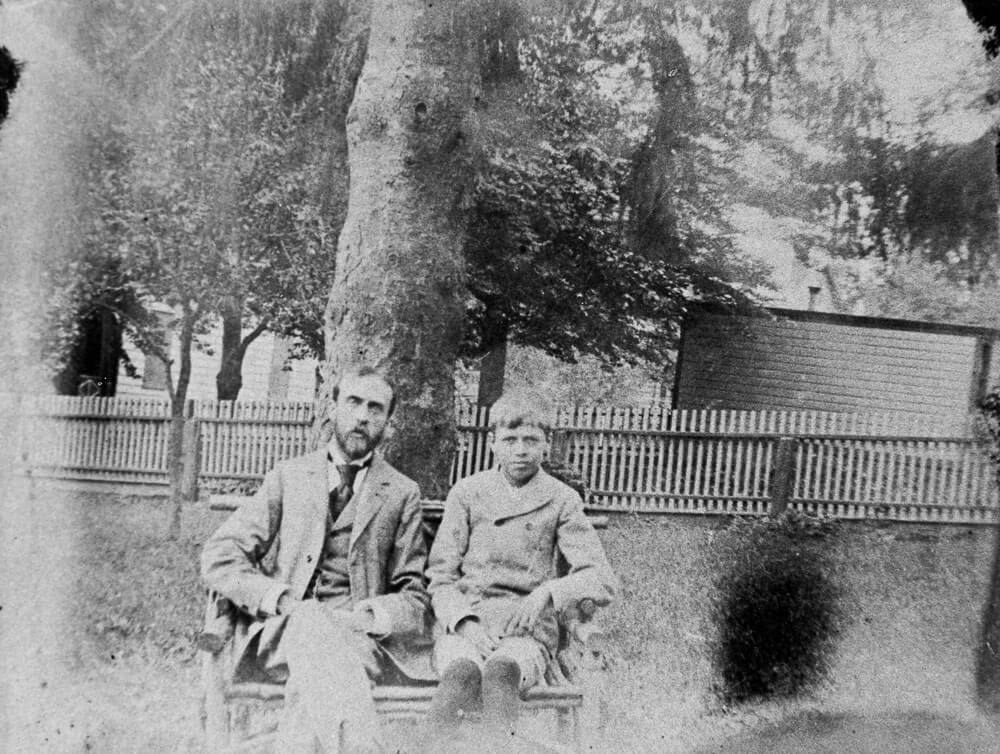

A clever sketch appended to the letter and titled “On the Watch” portrays his father atop their Nyack residence, equipped with a telescope and seemingly observing his son at Camp Nyack from a distance. This letter raises intriguing questions about Edward’s sentiments toward his father’s involvement – was it viewed as intrusive, supportive, or perhaps a family jest? It remains an enigmatic correspondence.

The Dry Goods Store and Edward Hopper

Edward Hopper assisted in his father’s store after school, potentially affording him extra time and funds to frequent Hinton’s stationery store across the street, a preferred source for art supplies in Nyack. In 1905, at the age of 53, Garret Hopper retired, a decision that coincided with Edward’s completion of five years of art education in New York City at the age of 23. Garret seemingly endorsed Edward’s artistic pursuits and refrained from pressuring him into continuing the family business. In fact, the family supported Edward’s subsequent journey to Paris for artistic studies.

Edward, much like his father, didn’t inherit the trading instinct of his Dutch ancestors. He even despised his sole commission for payment, despite facing financial constraints at the time, as he painted Helen Hayes and Charles MacArthur’s residence, “Pretty Penny.”

Did Garret Handle Store Bookkeeping?

Edward’s practice of maintaining a single notebook to record his painting sales may have been influenced by observing his father’s meticulous focus on business profits and losses. Perhaps, he spent time involved in bookkeeping. If so, one legacy from his father’s business would be Edward’s consistent record-keeping, listing all the paintings he sold until his passing in 1967.

Edward undoubtedly felt gratitude for his decision to prioritize art over a career in dry goods. His lack of business acumen and social skills rendered him unsuited for such endeavors. However, the influence of his father’s business can be discerned in the clean, horizontal lines that characterize his paintings, perhaps inspired by the play of sunlight on his father’s fabric-laden shelves during his formative years.

Michael Hays is a 35-year resident of the Nyacks. Hays grew up the son of a professor and nurse in Champaign, Illinois. He has retired from a long career in educational publishing with Prentice-Hall and McGraw-Hill. Hays is an avid cyclist, amateur historian and photographer, gardener, and dog walker. He has enjoyed more years than he cares to count with his beautiful companion, Bernie Richey. You can follow him on Instagram as UpperNyackMike