The Late Dr. Travis Jackson often quoted this African proverb: “Until the lions have their own historians, the history of the hunt will always glorify the hunter.”

As one of the 49 children at the center of a successful desegregation case in Rockland County in 1943, Dr. Jackson was a special guest at a ceremony in Hillburn, New York on Saturday, May 17, 2014.

The event commemorated the 60th anniversary of a subsequent legal decision, the landmark Brown V. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas. The program also remembered the lawyer who was on the winning side in both cases, Thurgood Marshall. As an eyewitness to this epic hunt for equality, Jackson has become the historian for the lions.

Dr. Travis Jackson

Before Thurgood Marshall helped dismantle discrimination in education through the Brown decision, and literally changed the complexion of the Supreme Court by becoming the first black Justice, he came to Rockland County to argue a desegregation case.

Like most public school students of color in mid-20th century America, Travis Jackson did not have a white classmate for a significant portion of his education. This demographic detail was not coincidental, but by design and accomplished with the pernicious misuse of public funds to maintain separate schools for black children.

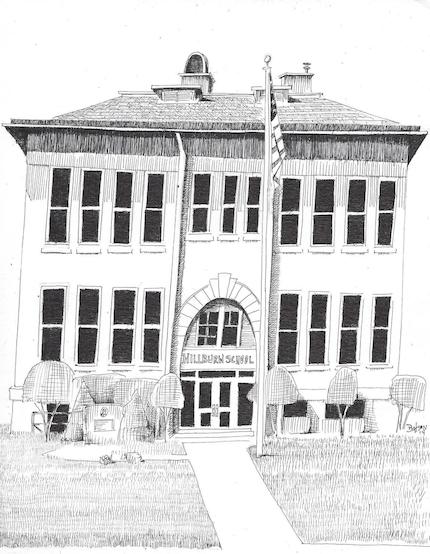

Jackson, and his father before him, attended the Brook School for Colored Children in the Village of Hillburn. Less than a mile away from the Brook School stood the Hillburn School, where only white students were enrolled. The Brook School was an unheated wooden structure with a small rocky playground in the front. The Hillburn School was modern and well equipped.

Rockland County Courthouse, 1943. Mrs. Van Dunk in the center with a coat draped over her folded arms. Marshall is the tall gentlemen to her left.

In 1943, Brook School parents, led by Mrs. Marion Van Dunk, engaged the services from a young attorney with the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People’s Legal Defense Fund.

When Thurgood Marshall came to Hillburn to defend the constitutional rights of elementary school students, Travis Jackson was entering the fourth grade.

Parents withheld their children from attending the Brook School in September of 1943 to protest the separate and unequal elementary school system. By October, their tactic and their legal counsel prevailed. The New York State Commissioner of Education closed the Brook School and ordered that all 49 children be admitted into the Hillburn School on Mountain Avenue.

Nyack resident and First Lady of the American Stage Helen Hayes was quoted at the time as having said: “I look forward with hope and prayer to developments in Hillburn…I am sure that the white people in Hillburn will have faith in democracy and…meet the situation with tolerance and understanding. Their audience today is as wide as the world.”

Brook students being turned away from the Hillburn School

In Hillburn, white families must have gotten a different memo. In the aftermath of the integration order, one parent told a reporter about a new committee that had been formed: “We’ll call it the Association for the Advancement of White People,” the parent said. “The Negroes have their association. We are forced to have ours.”

When a nine- year old Travis Jackson reported to school on the first day of integrated education in Hillburn, only one white student remained, briefly. Even though the desegregation of the school system was instituted during his fourth grade year, it was not until the seventh grade that the racial composition of the student body began to diversify.

To avoid an association with students of a different race, white families sent their children to nearby parochial schools. But that strategy had its limitations. “I guess private schools eventually became too expensive, new families moved in and others saw that the world was not coming to an end,” Jackson said. Integration eventually took hold.

When Jackson graduated from Suffern High in 1952, six of the 83 students in his graduating class were black Brook School alumni. Jackson went on to obtain his Doctorate in Education and serve as an educator and administrator for over three decades in schools in Suffern and northern New Jersey.

In 1954, Marshall and his colleagues at the NAACP Legal Defense Fund successfully argued Brown, ending segregated public schools in America. The reaction in some communities was similar to the initial response in Hillburn. One of the most dramatic examples of resistance was in Arkansas, where President Dwight Eisenhower had to send in the National Guard to ensure the safety of black students during the process of integrating Little Rock High School.

An activist, artist and writer, Bill Batson lives in Nyack, NY. Nyack Sketch Log: “When Thurgood Marshall Came to Rockland“ © 2023 Bill Batson. Visit billbatsonarts.com to see more.