by Bill Batson

by Bill Batson

Rockland County Civil Rights Icon Dr. Travis Jackson passed away last week. He was 87. In his honor, Nyack Sketch Log is reposting this column outlining the historic role he played in the battle to integrate schools in our county. Dr. Jackson was fond of quoting this African proverb: “Until the lions have their own historians, the history of the hunt will always glorify the hunter.” Through his work as an educator, and a participant in the documentation of the school desegregation case that brought Thurgood Marshall to Hillburn in the 1940s, Dr. Jackson became the historian for the lions. He did his pride proud.

Visitation is scheduled for 4-8 p.m. on Wednesday, June 30, and Thursday, July 1, at Wanamaker & Carlough Funeral Home, 177 Route 59, Suffern. Funeral services are planned for 10:30 a.m. Friday, July 2, at Wanamaker & Carlough in Suffern.

As one of the 49 children at the center of a successful desegregation case in Rockland County in 1943, Dr. Travis Jackson was the special guest at a ceremony in Hillburn, New York on Saturday, May 17, 2014. The event commemorates the 60th anniversary of a subsequent legal decision, the landmark Brown V. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas. The program will also remember the lawyer who was on the winning side in both cases, Thurgood Marshall.

Dr. Travis Jackson

Before Thurgood Marshall helped dismantle discrimination in education through the Brown decision, and literally changed the complexion of the Supreme Court by becoming the first black Justice, he came to Rockland County to argue a desegregation case.

Like most public school students of color in mid-20th century America, Travis Jackson did not have a white classmate for a significant portion of his education. This demographic detail was not coincidental, but by design and accomplished with the pernicious misuse of public funds to maintain separate schools for black children.

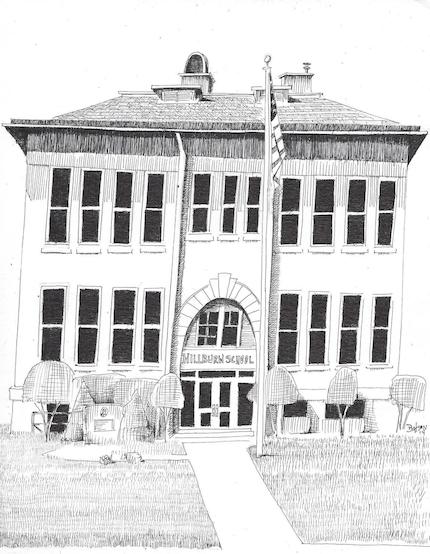

Jackson, and his father before him, attended the Brook School for Colored Children in the Village of Hillburn. Less than a mile away from the Brook School stood the Hillburn School, where only white students were enrolled. The Brook School was an unheated wooden structure with a small rocky playground in the front. The Hillburn School was modern and well equipped.

Rockland County Courthouse, 1943. Mrs. Van Dunk in the center with a coat draped over her folded arms. Marshall is the tall gentlemen to her left.

In 1943, Brook School parents, led by Mrs. Marion Van Dunk, engaged the services from a young attorney with the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People’s Legal Defense Fund. When Thurgood Marshall came to Hillburn to defend the constitutional rights of elementary school students, Travis Jackson was entering the fourth grade.

Parents withheld their children from attending the Brook School in September of 1943 to protest the separate and unequal elementary school system. By October, their tactic and their legal counsel prevailed. The New York State Commissioner of Education closed the Brook School and ordered that all 49 children be admitted into the Hillburn School on Mountain Avenue.

Nyack resident and First Lady of the American Stage Helen Hayes was quoted at the time as having said: “I look forward with hope and prayer to developments in Hillburn…I am sure that the white people in Hillburn will have faith in democracy and…meet the situation with tolerance and understanding. Their audience today is as wide as the world.”

Brook students being turned away from the Hillburn School

In Hillburn, white families must have gotten a different memo. In the aftermath of the integration order, one parent told a reporter about a new committee that had been formed: “We’ll call it the Association for the Advancement of White People,” the parent said. “The Negroes have their association. We are forced to have ours.”

When a nine- year old Travis Jackson reported to school on the first day of integrated education in Hillburn, only one white student remained, briefly. Even though the desegregation of the school system was instituted during his fourth grade year, it was not until the seventh grade that the racial composition of the student body began to diversify.

Fraternity That Makes and Preserves History

A solemn and substantial monument to the Hillburn Case, with an ethereal portrait of Thurgood Marshall carved into the stone, was erected by the legendary attorney’s fraternity brothers Alpha Phi Alpha. Founded in 1906, Alpha Phi Alpha is the oldest collegiate fraternal order for African Americans in the United States. Prominent past members include W.E.B Du Bois, Paul Robeson, Martin Luther King Jr., and Adam Clayton Powell, Jr. Thurgood Marshall pledged the fraternity at Lincoln University in Pennsylvannia.

A solemn and substantial monument to the Hillburn Case, with an ethereal portrait of Thurgood Marshall carved into the stone, was erected by the legendary attorney’s fraternity brothers Alpha Phi Alpha. Founded in 1906, Alpha Phi Alpha is the oldest collegiate fraternal order for African Americans in the United States. Prominent past members include W.E.B Du Bois, Paul Robeson, Martin Luther King Jr., and Adam Clayton Powell, Jr. Thurgood Marshall pledged the fraternity at Lincoln University in Pennsylvannia.

After his tenure at the NAACP Legal Defense Fund, Marshall was appointed to the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit by President John F. Kennedy. Later, he served as the Solicitor General for President Lyndon Johnson. President Johnson nominated him for the United States Supreme Court in 1967, making him the first African American Justice when he was confirmed by the Seante. Justice Marshall died in 1991.

The Eta Chi Lambda Chapter of Alpha Phi Alpha in Rockland County began a scholarship fund in 1963 to honor of Marshall’s role in Brown v. Board Education. The fraternity announces their annual awards on the anniversary of the Brown, May 17.

When the late Dr. Willie Bryant moved to Rockland County in 1976, he was urged by fellow frat brother, John Harmon, Director of the African American Cultural Foundation of Westchester County, to preserve and commemorate the work that Marshall had accomplished in Hillburn.

As coordinator of the Thurgood Marshall Project, Dr. Bryant won the support of Hillburn Mayor James Brown and Superintendent of the Ramapo Central School District Dr. Robert McNaughton to erect the monument in 2002. In 2008, members of Alpha Phi Alpha joined NYS Assemblymember Ellen Jaffee in Albany for the adoption of her resolution that made May 17 Thurgood Marshall Day in New York State.

In 2019, Dr. Jackson was present when a stretch of Route 17 was renamed Thurgood Marshall Memorial Highway.

An interview with Dr. Jackson is featured in Joe Allens film, Two Schools in Hillburn. The award winning documentary is available on Amazon Prime.

To avoid an association with students of a different race, white families sent their children to nearby parochial schools. But that strategy had its limitations. “I guess private schools eventually became too expensive, new families moved in and others saw that the world was not coming to an end,” Jackson said. Integration eventually took hold. When Jackson graduated from Suffern High in 1952, six of the 83 students in his graduating class were black Brook School alumni. Jackson went on to obtain his Doctorate in Education and serve as an educator and administrator for over three decades in schools in Suffern and northern New Jersey.

In 1954, Marshall and his colleagues at the NAACP Legal Defense Fund successfully argued Brown, ending segregated public schools in America. The reaction in some communities was similar to the initial response in Hillburn. One of the most dramatic examples of resistance was in Arkansas, where President Dwight Eisenhower had to send in the National Guard to ensure the safety of black students during the process of integrating Little Rock High School.

Supreme Court decisions, like Brown, had a profound impact on America by ending state-sanctioned discrimination. Decisions by the current high court, in areas from voting rights to affirmative action, signal the removal of the legal remedies that were enacted to address a legacy of racial discrimination in our country. Recent comments by onetime Tea Party darling Cliven Bundy and Los Angeles Clipper’s former owner Donald Sterling suggest that many of the same racial antagonisms that were prevalent before Brown endure.

But for those who may feel dispirited by recent racial discord, near and far, Jackson’s description of Hillburn after public school integration is reassuring. According to Jackson, the resentments of the adults of that period did not trickle down to their children. “Many of my friends, who are white and grew up in Hillburn, never got why they were dragged out of their school in 1943. Today Hillburn is one of the most integrated areas of Rockland – integrated economically, politically, and socially. It is also a nice place to live,” Jackson added.

Special thanks to Cathy Quinn of the Historical Society of Rockland County, Gini Stolldorf and Jennifer Rothschild of the Historical Society of the Nyacks, and Tiffany Card, Rose A. Gabriel-Leandre and Michele McCarthy of Assemblywoman Ellen Jaffee’s office. Much of my research was made possible by the scholarship of Dr. Travis Jackson and Dr. Willie Bryant.

An activist, artist and writer, Bill Batson lives in Nyack, NY. Nyack Sketch Log: “Farewell to Rockland County Civil Rights Icon Dr. Travis Jackson“ © 2021. Bill Batson. Visit billbatsonarts.com to see more.