by Bill Batson

by Bill Batson

As a documentarian, Joe Allen uses films to explore the perverse arithmetic of racism and antisemitism. In Two Schools in Hillburn, Allen exposed the binary cruelty of racial segregation that was tolerated in one town in Rockland County well into the 1940s, a practice brought to an end by a young attorney from the NAACP named Thurgood Marshall. His previous film, 20 Million Minutes chronicled the interval between the massacre of 11 Jewish athletes at the Olympic Games in Munich, Germany in 1972 and the launching of a campaign to get the International Olympic Committee to commemorate the atrocity, a struggle that persists. Allen’s documentaries are helping new generations seek answers to seemingly intractable social problems.

Leadership Rockland will be showing “Two Schools in Hillburn,” tonight, Tuesday, September 24 at the Lafayette Theater in Suffern. Doors open at 6. There will be Q & A after the screening. The event is free to all Leadership Rockland alumi.

Leadership Rockland will be showing “Two Schools in Hillburn,” tonight, Tuesday, September 24 at the Lafayette Theater in Suffern. Doors open at 6. There will be Q & A after the screening. The event is free to all Leadership Rockland alumi.

Nyack Sketch Log sat down with Allen to learn how he uses film to find social equations for equality.

When did you make your first documentary?

I made my first documentary in 2011 and 2012. It was the story of the terrorist attack on the Israeli athletes at the Munich Olympics in Munich Germany in 1972 that killed 11 Israeli athletes. It tells the story of how JCC Rockland got involved with the families of the Munich 11 in an effort to move the International Olympic Committee to grant a minute of silence on the behalf of the murdered athletes.

What was the impetus?

What was the impetus?

JCC Rockland was, for the first time ever, going to host the JCC Maccabi Games, which is an Olympic-style event held all around the world for Jewish youth. At each set of games, there is a memorial to the Munich 11 during the opening of the event. JCC CEO David Kirschtel and I spoke about how Active International, the company I was working for at the time, could be involved in the games. During the course of that conversation, I asked David if he was documenting what JCC Rockland was doing at the games, and especially what he was planning to do for the Munich 11? At that moment the documentary, which was “20 Million Minutes,” was born.

In what field was your career?

In what field was your career?

I have been very fortunate to have a career that spanned being a journalist, a corporate spokesperson, owning a small ad agency, being a writer and spending 25 very productive years at Active International, where I was in charge of corporate communications as well as heading up its philanthropic program, which we called Active Cares. I am now retired from Active and I am now a full-time filmmaker. I also consult on nonprofit and philanthropic issues as well as remaining involved in the nonprofit committee in Rockland.

What did you learn from making “20 Million Minutes?”

What did you learn from making “20 Million Minutes?”

What was notable in the making of that film was the impact that JCC Rockland had on the world in bringing to light the issue of the Munich 11 and the lack of the victims being remembered at the Olympic Games where they participated and died. We didn’t expect the worldwide coming together of support of remembering these guys that we saw come about. After all, for 40 years their families were dismissed.

How far and wide has the film been distributed?

How far and wide has the film been distributed?

That particular film had a very narrow distribution and, in fact, that was a motivation to do a sequel, “There Was No Silence,” which premiered on Sept. 5, the 47th anniversary of the Munich Massacre. It tells the story of the 2012 Olympics, which the first movie focused on, but on all the things that have happened regarding the Munich 11 heading into the Tokyo Olympics in 2020. Where “20 Million Minutes” ran at just under 90 minutes and was overwhelmingly Rockland County-centric, the sequel runs at around 50 minutes to make it more palatable for younger people in schools, senior citizen groups, civic groups and others and to make it more acceptable to a national and even worldwide audience.

When did you pick the Brook School for Colored Children as a topic?

When did you pick the Brook School for Colored Children as a topic?

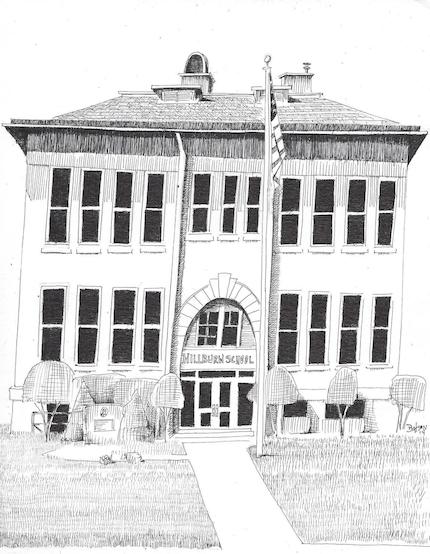

Cliff and Wylene Wood came to see my film about Hudson Valley Honor Flight, which was being shown in the Rockland Community College Theater in December 2015. Cliff Wood was president of the school at the time and Wylene was extremely well known in corporate responsibility circles, teaching civil rights circles. Shortly after they saw the film, Wylene called me and asked if I would be interested in doing a short video that could be shown in Hillburn at the dedication of the Main School as both federal and state historical place.

I began to do the research for that short video and realized what an important story it was, not just to Hillburn, nor to Rockland County, but to the entire country. For one, it brought a young attorney named Thurgood Marshall to Rockland to litigate the case and make the appeal to allow children of color to attend the all-white school. More than that, the Hillburn case taught Mr. Marshall many of the things he would need to know about Jim Crow (separate but equal) laws and attitudes as he prepared for Brown versus Board of Education of Topeka, KS 10 years later. If the so-called Brown case is one of our country’s most important cases, then Hillburn was the place where he learned how to argue it.

I began to do the research for that short video and realized what an important story it was, not just to Hillburn, nor to Rockland County, but to the entire country. For one, it brought a young attorney named Thurgood Marshall to Rockland to litigate the case and make the appeal to allow children of color to attend the all-white school. More than that, the Hillburn case taught Mr. Marshall many of the things he would need to know about Jim Crow (separate but equal) laws and attitudes as he prepared for Brown versus Board of Education of Topeka, KS 10 years later. If the so-called Brown case is one of our country’s most important cases, then Hillburn was the place where he learned how to argue it.

Any thoughts on Thurgood?

Any thoughts on Thurgood?

Thurgood Marshall was a trailblazer for sure. He was part of the pre-civil rights legislation efforts that really laid the groundwork for what LBJ did in the early to mid 60s. But more than that, Thurgood Marshall was still one of the people who had a really difficult time making their way through really tough, segregated parts of both the South and the North in order to argue cases. Obviously, I didn’t know him so I can’t say things like he was fearless, but he and along with so many others of his generation appear to be fearless and were role models for those who came after them. They believed what’s right is right and that the effort get to what’s right should know no bounds.

His son, John, told me a story of not really knowing that his father was such an important man until one day he found himself on LBJ’s lap in the Oval Office, right when his dad was about to become a Supreme Court Justice–and only then did he figure that his dad was a pretty big deal. I also learned Thurgood Marshall had an affinity for model trains and, in fact, had a sophisticated train set-up in his apartment in New York. There were times when his interns would drop something off to his apartment and Thurgood would answer in full train regalia, hat and all.

His son, John, told me a story of not really knowing that his father was such an important man until one day he found himself on LBJ’s lap in the Oval Office, right when his dad was about to become a Supreme Court Justice–and only then did he figure that his dad was a pretty big deal. I also learned Thurgood Marshall had an affinity for model trains and, in fact, had a sophisticated train set-up in his apartment in New York. There were times when his interns would drop something off to his apartment and Thurgood would answer in full train regalia, hat and all.

Did the film making process reveal anything about the case that was not widely known?

Did the film making process reveal anything about the case that was not widely known?

The whole story was not widely known, I had lived in Rockland County for many years and I didn’t know about it. Many other people who worked in the media here also didn’t know about it. Some of the old-timers or some of our historians in the County knew about it, but the most surprising thing was that a case that was so essential to our entire country got very little airing and had very little publicity about it. The people in Hillburn knew about it but it wasn’t well-known in the county.

How are you feeling about the state of racial equality in American schools in 2019?

How are you feeling about the state of racial equality in American schools in 2019?

I believe we are standing on the edge of a very high and very narrow cliff these days. And while it’s true that there are laws on the books which will help to prevent inequality, it does feel that we are retreating and retrenching into some very bad historical portals. The gap between rich and poor and the tribal nature of our behavior is making us turn to our neighbors and viewing those that don’t look like us or spend like us or enjoy what we enjoy or see America the way we see America as being part of the “other.”

Slowly but surely that attitude will erode the very symbols upon which we fought so hard to achieve together. It’s very difficult to say the state of racial relationships in schools and in society is a whole lot better now than it was. We are very lucky and at the same time cursed that there is such a plethora of media and commentary around us at all times. It’s much harder to miss an act of racial insensitivity or violence when everyone’s got a cell phone or camera and the media essentially is everywhere. That means what we do may be out there for all to see, forever–and when our behavior is bad that’ll be all over the news and all over the social media sites very quickly. Add to that, having a President who revels in that fact and endlessly stirs the pot and you have two sides who grow increasingly angry trying to find ways to deal with one another. The president’s zero-sum games all too often become our zero-sum games. You either support the police or you support entities like Black Lives Matter. But it’s never one or the other and yet we’re being forced to declare which side we are on? And we’re endlessly trying to put a square peg into a round hole by behaving that way.

Slowly but surely that attitude will erode the very symbols upon which we fought so hard to achieve together. It’s very difficult to say the state of racial relationships in schools and in society is a whole lot better now than it was. We are very lucky and at the same time cursed that there is such a plethora of media and commentary around us at all times. It’s much harder to miss an act of racial insensitivity or violence when everyone’s got a cell phone or camera and the media essentially is everywhere. That means what we do may be out there for all to see, forever–and when our behavior is bad that’ll be all over the news and all over the social media sites very quickly. Add to that, having a President who revels in that fact and endlessly stirs the pot and you have two sides who grow increasingly angry trying to find ways to deal with one another. The president’s zero-sum games all too often become our zero-sum games. You either support the police or you support entities like Black Lives Matter. But it’s never one or the other and yet we’re being forced to declare which side we are on? And we’re endlessly trying to put a square peg into a round hole by behaving that way.

Two of your topics engage in tolerance toward the Jewish and African American communities do you perceive parallels between these two communities?

Two of your topics engage in tolerance toward the Jewish and African American communities do you perceive parallels between these two communities?

Both those communities have felt the sting of stereotype and hatred through the years. Anti-Semitism and racism are found at the bottom of the same boiling cauldron of hate that our country unfortunately has as part of its very being. Our original sin of slavery and our original sin of displacing Native Americans fit in squarely with anti-Semitism.

I always believed that groups who have been ostracized and hated for what they are and then marginalized would be better in a unified approach to overcoming all that. I remember growing up with a lot of progressive Jews that were closely aligned with the civil rights struggle. I’m guessing they still are, so I don’t know why African Americans and Jews are not more tightly wound together.

I know you are actively engaged in the community through your work with People to People and other nonprofits. Have you and your camera lens taken on the issue of hunger in America? What is your next project and where can we see it?

I know you are actively engaged in the community through your work with People to People and other nonprofits. Have you and your camera lens taken on the issue of hunger in America? What is your next project and where can we see it?

The newest project is the sequel to “20 Million Minutes.” As I said earlier, that film is called “There Was No Silence.” That film has a director’s cut premier on September 5 and will be widely released a bit later in the fall.

Now as far as hunger in America, we are down the road on a film called “Empty Cupboards.” It is about hunger in America and the way different communities are relying on their own capabilities and wherewithal to stay ahead of it without relying on the federal government for the solution. Government can pay part of the solution, but they can’t provide all of it as that gives too much power to the feds to solve the problem local communities. Organizations recovering food, changing raw materials in food production, presenting innovative ways of growing food and distributing what we grow, are in my opinion, leading the way in which we are going to solve the problem of hunger in America.

Now as far as hunger in America, we are down the road on a film called “Empty Cupboards.” It is about hunger in America and the way different communities are relying on their own capabilities and wherewithal to stay ahead of it without relying on the federal government for the solution. Government can pay part of the solution, but they can’t provide all of it as that gives too much power to the feds to solve the problem local communities. Organizations recovering food, changing raw materials in food production, presenting innovative ways of growing food and distributing what we grow, are in my opinion, leading the way in which we are going to solve the problem of hunger in America.

We throw away 40% of all food manufactured in the US. That alone is enough to feed everyone and what we’re throwing away isn’t the bad stuff, it’s the stuff that wasn’t perfectly shaped or perfectly colored or too much of which was put out in the buffets and now can’t be used. We need to think smarter and we need to think how to save our communities that are at risk for hunger. That film will be out in the first half of next year. You can expect that film to have a very wide distribution!

An activist, artist and writer, Bill Batson lives in Nyack, NY. Nyack Sketch Log: “Joe Allen, Documentarian“© 2019 Bill Batson. Visit billbatsonarts.com to see more.