by Bill Batson

by Bill Batson

Pat Hickman allows us to communicate with rivers, volcanoes, and wind, forces that shape our physical existence. Fabric, steel, wood, membrane, the ubiquitous material that surround us, have become mostly silent to western ears. As materialistic as we have become, oddly, we are not on speaking terms with the natural world. Pat Hickman can translate.

Her work reveals the universe that exists beneath the bark of a tree or below the surface of water, or the language a Muslim woman in Turkey speaks through the edging of her scarf. Like the creative process that John Updike described in the Blessed Man from Boston, as an artist, Hickman “walks through volumes of the unexpressed and like a snail leave(s) behind a faint thread.”

Meet Pat Hickman.

Could you say a few words about your current show at Ray Lagstein’s Galllery, Floodlines: Water Rises?

Could you say a few words about your current show at Ray Lagstein’s Galllery, Floodlines: Water Rises?

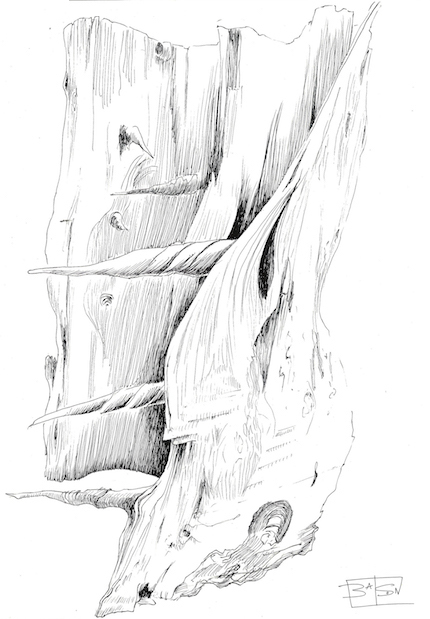

I live above the Hudson, in Dutchtown, high enough that I don’t expect the Hudson to rise to the level of my house. But after recent hurricanes, here and there, and frequent news of water rising, ice melting, and many subsequent disasters due to climate change in so many parts of the world, I feel that we must heed the warning and not ignore what is happening. My installation of river teeth suggests water surging with rivulets of river teeth pouring across the gallery floor. Drawings of individual river teeth fill the walls. These drawings are not treated as precious, but layered and attached in an almost helter-skelter way, disordered and confused, almost as birds flying in retreat, as water rises. The bottom two layers of drawings have been sprayed with water, establishing the floodline, allowing the walnut ink of some of the drawings to drip down, tear-like.

When did you first discover river teeth? How long have they been featured in your work?

When did you first discover river teeth? How long have they been featured in your work?

When I was at Haystack Mountain School in Deer Isle, Maine in 2008, I overlapped with artist Dorothy Gill Barnes, who introduced me to a river tooth found there in the woods. She had used a very few river teeth in her sculptural baskets. She also pointed me to the writer, David James Duncan, and his “River Teeth: Stories and Writings.” I became intrigued with the idea, function, shape and potential meaning of river teeth and collected them on subsequent times at Haystack when I was there either teaching a workshop or as part of an open studio residency. I exhibited my first installation of them at the Tovin Gallery in Nyack in 2011. Over the past eight years, I have created several reconfigured, different installations, of river teeth at other venues.

Pat Hickman: Staying Time; Nyack, NY

Was your studio at Garnerville damaged by the floods after Hurricane Irene?

No, my studio on the second floor of my building was not damaged, but the impact was felt. Images of water rushing through the complex from Minisceongo Creek overflowing were shocking and meant damage for so many tenants there—loss of equipment, of artwork, of work space, of the gallery. For two months, we had no water or heat. Even if we didn’t know all those affected, it had a huge influence on the community and that historic site. We wondered if flooding could happen again, if Garner could bounce back. There was a sense of loss.

Did you acquire any material for your work from that flood?

Did you acquire any material for your work from that flood?

When water was released upstream from Harriman Park, debris from higher up the creek jammed up the flow, causing damage below. By the time it surged through the Garner complex, this debris was crashing against the old brick walls and buildings. Before that, I had molded gut (skin membrane) over a 19th century elevator door that had been saved and attached to the outside wall in Brick Alley. I loved that door and wanted to pick up (transfer onto the gut) the memory of the rust marks, making reference to the history of Garner. I created a piece I called “Calicoed by Rust”, thinking of the rust marks almost like small printed designs as on the calico the factory made. After the hurricane, after the damage—even though that elevator door survived, I felt the piece needed to reflect what had happened with water pouring through that narrow alleyway. On top of the calicoed surface, I added layers of molded shapes of rusty railroad plates, for holding down railroad ties—as heavy metal had come loose and floated down the creek. I didn’t literally acquire those railroad plates from the flood, but what I did with them made reference to the flood damage, changing that place forever. I entitled the reworked piece, “Downriver Ravages”

What are some of the other seen and unseen natural forces that shape your work?

What are some of the other seen and unseen natural forces that shape your work?

I think about “life force” and the miracle of bodies working mostly as well as they do. When I first saw a gut parka from Alaska, made of seal or walrus intestine, I found the idea of the translucent membrane beautiful, transformed into a wearable, protective outer waterproof garment. I became interested in that which is unseen, in the interior of a body, that it can become seen, given new life.

I wanted to experiment with skin membrane that might be accessible to me. I started exploring what I might do with sausage casings (hog casings) which I now get from www.sausagemaker.com A lot of my work addresses the fragility of life, bringing ideas of life and death together with the use of this skin membrane. In covering river teeth with skin membrane, I take that which is inside a tree, invisible from the outside—the river tooth which is holding a branch to the tree trunk—and make it visible, combining the unseen from the plant world with the unseen from the animal world, bringing them together, making both visible. My father was a butcher. As a child growing up in small town in rural CO, I had trouble watching dad butcher animals for relatives who raised cattle. Perhaps the idea of giving another chance for life grew out of those childhood memories of such family gatherings.

Having lived and taught in Hawaii for 16 years, I remain awed by the force of the volcano on the Big Island and massive flowing lava, resulting in incredible formations in black lava fields. I’m moved by that unseen power and energy when it’s made visible, sometimes in horrific, destructive ways. I have not found ways to have this shape my work, as it seems impossible to imitate or duplicate the beauty and power of nature, though designing the monumental entrance gates for the Maui Arts & Cultural Center (1991-1994) and working with the foundry at the University of Tasmania, is the closest I’ve come to fire and molten metal in casting.

In addition to Updike’s quote about the “volumes of the unexpressed,” that you shared at the Nyack Center Pecha Kucha event in 2016, who are some of the artists that inspire you?

In addition to Updike’s quote about the “volumes of the unexpressed,” that you shared at the Nyack Center Pecha Kucha event in 2016, who are some of the artists that inspire you?

At the University of CA, Berkeley, where I did my graduate work, I was fortunate to study with and have as mentors: Ed Rossbach and Lillian Elliott. They and their work had an impact on my thinking, my way of working. I also consider Katherine Westphal a mentor.

I’m inspired by the work of Ann Hamilton, Doris Salcedo, Kimsooja, Ursula von Rydingsvard, Sonya Clark, Joyce Scott, Jim Bassler, etc. The list could go on much longer.

What are some of the places that inspire you?

What are some of the places that inspire you?

Where I live by the Hudson. Istanbul (on the Bosphorus) and Cappadocia in Turkey; the Big Island of Hawaii, the Northern CA coast, the Maine woods AND cities and museums almost everywhere.

What are some of the materials that inspire you?

Example of Seal Gut Parka from northern Alaska

I come out of a textile tradition and respond to the expressiveness of cloth, of fibrous materials, of flexible linear materials, of making something out of seemingly nothing, of forgiving materials. I use natural materials, reeds and branches, found materials, rusted materials, paper—that which speaks of time and memory, of materials which feel close to life. I create structure out of stiff materials which I can manipulate, sometimes covering structures with skin membrane. I find materials which express what I’m trying to say in my artwork.

Who are some of the people that inspire you?

James Baldwin, Nelson Mandela, Jacinda Ardern

In addition to termites, who are some of your other collaborators?

In addition to termites, who are some of your other collaborators?

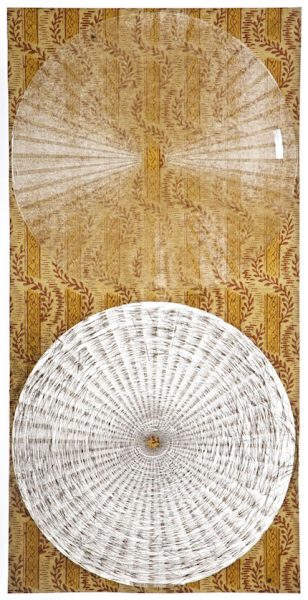

I consider “Ripples”, a piece I created with found or gifted dead geckoes in Hawaii, to be in collaboration with them, with their tiny life-like gestural bodies which I stitched around and which led to the shape and meaning of the work. And yes, responding to the work of termites, I have created a couple of pieces responding to their creations—to the beauty of chewed lace-like wooden beams to a mound I found termites had made in the bush in Australia. I had a long term eleven year artistic collaboration in the ‘80s & early ‘90s with Lillian Elliott, a mentor and colleague in Berkeley, CA. We exhibited collaborative work for those many years but always did our own individual work during that time, sharing a studio. I sometimes now collaborate  with David Bacharach, an artist in Baltimore, who creates structures in metal which I cover with skin membrane, each bringing our own materials and way of working to the artwork.

with David Bacharach, an artist in Baltimore, who creates structures in metal which I cover with skin membrane, each bringing our own materials and way of working to the artwork.

You’ve referenced Hawaiian and Alaskan myths and practices in your work, could you describe those two and a few others cultures that inspire you?

In Hawaii, from Native Hawaiian students and others, especially from the Pacific Islands, I came to understand a deep connection to the living earth, and all that is on it—knowledge that has been understood by indigenous peoples from the beginning—but I had not experienced it or taken it in, as much as I did the years I lived and taught at the University of Hawaii. I became much more aware of non-Western ways of thinking, realizing how my own perspective was from a Western point of view, from Western based education central to my view of the world. I saw first hand what damage colonization had done in Hawaii and the complicated history of that place, still burdened by tourist stereotypes of “paradise” and needing to believe a place like Hawaii exists. I learned a lot by living there.

Over several summers, I taught workshops in Alaska at the University of AK Fairbanks. For the San Francisco Craft & Folk Art Museum, I guest curated an exhibition “Innerskins/Outerskins: Gut and Fishskin”, borrowing objects from provincial museums in AK. Through my research for that exhibit and catalogue, I gained a keen sense of respect Native Alaskans have for other animals, for example when seals gave their lives to a community, Yup’iks saved and inflated the bladders from those animals and ceremoniously offered them back to the sea as a thank you for those animals who had given their lives to sustain the life of the community.

Over several summers, I taught workshops in Alaska at the University of AK Fairbanks. For the San Francisco Craft & Folk Art Museum, I guest curated an exhibition “Innerskins/Outerskins: Gut and Fishskin”, borrowing objects from provincial museums in AK. Through my research for that exhibit and catalogue, I gained a keen sense of respect Native Alaskans have for other animals, for example when seals gave their lives to a community, Yup’iks saved and inflated the bladders from those animals and ceremoniously offered them back to the sea as a thank you for those animals who had given their lives to sustain the life of the community.

I am fortunate to have lived in Turkey for seven years, going there originally to teach in a Turkish Girl’s school. I became very interested in the language of communication, silent communication among women, understood from the edging on their headscarves—needlelace edging in tiny shapes—which conveyed innermost feelings of the wearer. For example, edging a woman wore could say that she was pregnant, that she was arguing with her husband, that her son was going to the army, etc. Meaning could be communicated through barely visible 3 dimensional minuscule net-like structures.

I am fortunate to have lived in Turkey for seven years, going there originally to teach in a Turkish Girl’s school. I became very interested in the language of communication, silent communication among women, understood from the edging on their headscarves—needlelace edging in tiny shapes—which conveyed innermost feelings of the wearer. For example, edging a woman wore could say that she was pregnant, that she was arguing with her husband, that her son was going to the army, etc. Meaning could be communicated through barely visible 3 dimensional minuscule net-like structures.

I have taught textile history and world textiles, believing that to be the core foundation for any program in Art in the Fiber Medium. There are cultures in so many places in the world that I/we learned from. Through their textiles and what was conveyed in others’ making and the role their work played in their own lives, I believe there are strong connections to the present.

I have taught textile history and world textiles, believing that to be the core foundation for any program in Art in the Fiber Medium. There are cultures in so many places in the world that I/we learned from. Through their textiles and what was conveyed in others’ making and the role their work played in their own lives, I believe there are strong connections to the present.

What are some of the things on your current to do list?

I am a list maker, have daily lists, things that get checked off, things that get moved to the next day’s list. I actually have saved and used those lists as art materials. I still save them. The black crossed off lines remind me of running stitches, lists become almost like a daily log, a diary of comings and goings throughout a day—a plan of what “to do”. Not always urgent, just how I think through what I might do each day. It’s a mark making habit—black/white pattern on a little notepad, pages then tucked away, for something that might come in the future. Mostly to anyone else, these appear as scraps of paper to be thrown away. I see them as “pure potential”, waiting to see what’s next. This phase of my  life is about seeing what I can do with my time in my artwork, in the studio, in relationships with family and friends, finding my way in a place that still seems new to me, traveling, going into the City as an adventure, experiencing new things, new places, new people. Even though those don’t get put down on a “to do” list, that’s what is there, unwritten.

life is about seeing what I can do with my time in my artwork, in the studio, in relationships with family and friends, finding my way in a place that still seems new to me, traveling, going into the City as an adventure, experiencing new things, new places, new people. Even though those don’t get put down on a “to do” list, that’s what is there, unwritten.

Are there more peoples and places that you wish to learn from?

Yes, always, wherever I go, whenever I have the opportunity to experience something new.

What’s next?

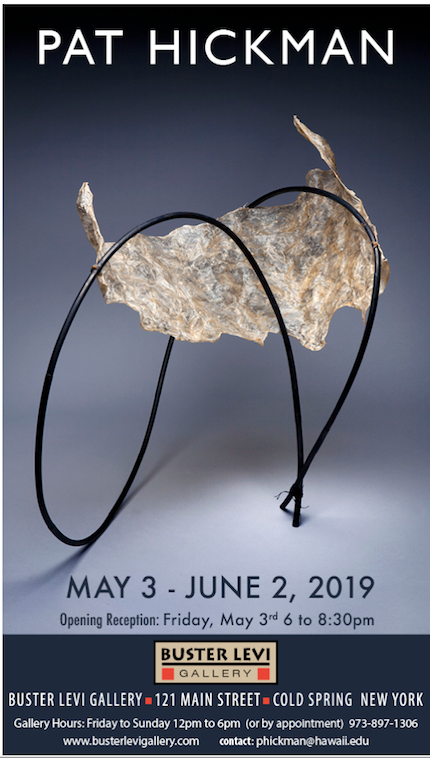

I have a solo exhibit opening May 3 at Buster Levi Gallery in Cold Spring.I have a residency scheduled for two weeks in July in Monson, Maine. I’m going, not knowing what I’ll do there but want to use that time to find the next direction, possibly new materials, just to see what will happen when I have uninterrupted time, without the distractions of daily life. Even though that’s a bit scary, I trust something will happen with this gift of time.

Pat Hickman: Floodlines: Water Rises is on display at the Lagstein Gallery until May 13. Founded by painter Ray Lagstein in 2014, the contemporary art gallery is located at 85 South Broadway. For more information visit lagsteingallery.com

To learn more about Pat Hickman visit pathickman,com

Bill Batson is an activist, artist and writer who lives and sketch logs in Nyack, NY. Nyack Sketch Log: “Pat Hickman’s River Teeth” © 2019 Bill Batson. To see more, visit billbatsonarts.com