by Bill Batson

by Bill Batson

Yesterday, people of all races and religions gathered for the observance of Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s birthday at Pilgrim Baptist Church. Our annual gathering, in its 32nd year, is a testament to the beloved community that Dr. King gave his life to establish. We should be proud that Nyack in 2019 embraces pluralism because a century and a half ago, no house of worship would open their doors to such diversity.

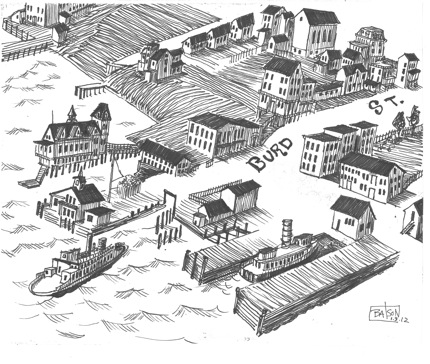

In 1884, Nyack, NY was a bustling river community and the commercial heart of Rockland County. This sketch is from a widely circulated map made by L. R. Burleigh. The bird’s-eye view rendering depicts a jumble of homes, businesses and churches. When you take a closer look at this historical document you’ll discover that our 19th century republic on the Hudson was not as indivisible as the promise made in our pledge of allegiance.

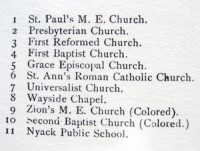

The 1884 map has a legend that designated 42 places of interest including ten churches. Eight of the churches are identified by denomination; the last two are listed by sect and by race. When I noticed this detail for the first time, it took my breath away. St. Philip’s African Methodist Episcopal Church, which stands today on the corner of North Mill and Burd Street, was listed in the legend as “Zion’s M.E. Church (Colored).” The church now known as Pilgrim Baptist and located at the corner of High Avenue and Franklin Street was identified as “Second Baptist Church (Colored).”

The 1884 map has a legend that designated 42 places of interest including ten churches. Eight of the churches are identified by denomination; the last two are listed by sect and by race. When I noticed this detail for the first time, it took my breath away. St. Philip’s African Methodist Episcopal Church, which stands today on the corner of North Mill and Burd Street, was listed in the legend as “Zion’s M.E. Church (Colored).” The church now known as Pilgrim Baptist and located at the corner of High Avenue and Franklin Street was identified as “Second Baptist Church (Colored).”

Twenty Five years ago, I travelled to rural Georgia to help a legal team exonerate a death row inmate named Curfew Davis. Needing the exact street address of a Baptist Church where we were expected for a meeting, I called information. When I asked the operator for the listing, in a deadpan drawl, she surprised me with her own question: she wanted to know which Baptist Church I sought. I said I didn’t

Twenty Five years ago, I travelled to rural Georgia to help a legal team exonerate a death row inmate named Curfew Davis. Needing the exact street address of a Baptist Church where we were expected for a meeting, I called information. When I asked the operator for the listing, in a deadpan drawl, she surprised me with her own question: she wanted to know which Baptist Church I sought. I said I didn’t

Bitter background of a sweet bag

Tote bag modeled by Bonnie Timm

My drawing of the L.R. Burleigh map adorns one of my first pieces of Nyack merchandise. Every time I see the tote bag, I experience a kind of cognitive dissonance. I loved this map, was pleased with my drawing of it, and the tote it inspired, but I can’t shake the ice-water-in-my-veins-feeling I got when I saw that the map’s legend constrained the religious choices of the people of Nyack in 1884 by race. Sometimes I see a sweet drawing. Sometimes I see the old Jim Crow.

know. She asked again and I got her drift. Even though it was 1990, the ghost of Jim Crow ran through the phone and down my spine. When I replied, “the black one,” she gave me the phone number.

I felt the same chill when I noticed the legend of the 1884 map. Was the distinction “colored” made as a boast; a proud assertion that the village accommodated two black churches? Was it a warning to prevent someone from walking into a congregation of clashing complexion: or something more ominous?

I was more saddened than shocked when I confronted the legacy of segregation in the South in the 1990’s. I knew that the removal of overt signs of discrimination, like those posted on water fountains and bathrooms in the 1960’s hadn’t ended racism, but it was sobering to consider that members of the same religious denomination still required separate houses of worship for each race.

When I observed a Jim Crow distinction on a map of Nyack, it was the geography that stunned me. I adopted the hubris of many Northerners, believing that the sins of human bondage were relegated to the South. Nyack should feel proud of our role in the 1800’s Underground Railroad network that helped slaves escape to the North. But if we believe that our landscape is not stained by slavery and segregation, we would be wrong.

As you uncover the more sordid aspects of a particularly contentious period of history, it is easy to think of the people of that era as characters in a period movie. But when the events took place where you live and the characters that navigated the social turbulence were your ancestors, each new detail is like a faint body blow.

My great-grandfather, George T. Avery, was a spokesperson for the black community and a member of Zion’s M.E. church at the time this map was drawn. From our vantage point today, the notation “colored” is an awkward relic of past discrimination. For the members of these two churches, the fact that the distinction was made in such a public fashion was of enormous social and material consequence.

My great grandfather, George T. Avery

A more noble aspect of our democracy is that we keep these ugly details of our evolution in our documents. We do not pretend that the abhorrent customs of American apartheid never existed. We resist the temptation to destroy the evidence of our troubled past.

You do not need to read far into the Constitution to be reminded that when apportioning congressional seats, black people were counted as three fifths of a person. It would be a profound injustice if some well-meaning printer sanitized copies of the Constitution, or the map of 1884 and removed these examples of racial discord. We honor the progress our society has made, the burdens of people like my great-grandfather and the members of St. Philip’s and Pilgrim, when we publish the unvarnished map of 1884, warts and all.

Bill Batson is an activist, artist and writer who lives and sketch logs in Nyack, NY. Nyack Sketch Log: “warts and all“ © 2019 Bill Batson. To see more, visit billbatsonarts.com