by Bill Batson

by Bill Batson

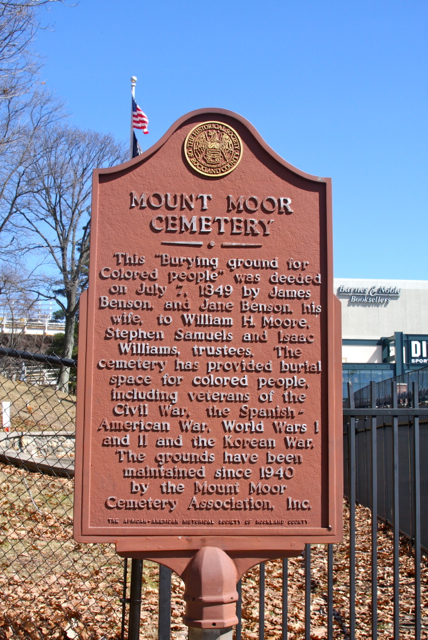

Cemeteries were segregated in America until the mid-20th century. Even black veterans of America’s armed conflicts were dishonored when buried. Today, Mount Moor Cemetery stands as a monument to the twisted logic of racial discrimination. But the cemetery of approximately 90 veterans and civilians also serves as a symbol of perseverance and defiance. The gravestones at Mount Moor endure, despite the initial efforts of the developers of the Palisades Mall to obliterate the burial ground.

(l.-r.) Hezekiah Easter Jr., Ruth Easter, Hezekiah Easter Sr.

A commemoration for African American Civil War veterans will be held at Mount Moor on Saturday, April 12, 2014 at Mount Moor at 1pm. The exploits of men who fought and died to preserve a democracy that did not grant them citizenship is one of the greatest tales of self-sacrifice in American history. Hollywood attempted to tell the story in the 1989 film “Glory,” staring Denzel Washington. However, our monument to this expression of epic heroism, Mount Moor, would not exist if not for a hometown hero, the late Hezekiah Easter, Jr.

United in Battle

Divided in Burial

There are 28 Civil War veterans known to be buried in Mount Moor. They served in the 26th and 45th New York Regiments of Colored Volunteers and the 54th Regiment of Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry. The 54th was the regiment that was recognized for their valor in the assault on Fort Wagner in South Carolina on July 18, 1863, the battle that was depicted in the movie “Glory.”

Daniel Ullman, one of the Union Army officers who convinced President Abraham Lincoln to mobilize African America troops during the Civil War, is buried in Nyack’s Oak Hill Cemetery. He organized five regiments known as the Corps d’Afrique and was elevated to the rank of Brigadier General.

Hezekiah Easter, Jr. became the first African American elected to public office in Rockland County when he won a seat on the Village of Nyack Board of Trustees in 1965. His connection to Mount Moor Cemetery was deeply personal. In 1945, he helped bury his brother Linwood, who died from a ruptured appendix at age 15. His father, Hezekiah Easter, Sr., a World War I veteran who owned a wood yard near the cemetery, was buried there in 1986. If the developers of the Palisades Mall had had their way, Hezekiah Easter, Sr. would have been the last burial at Mount Moor.

A copy of Mount Moor’s successful application for placement on the National Park Service’s Register of Historic Places documents how the cemetery was a significant landmark for a black community that has called Rockland County home for over three hundred years.

The recorded presence of African Americans in Rockland County began at the same time that Europeans arrived in the region. African slaves and free blacks were a part of the Dutch community that settled here in 1687. According to census records from 1723, nearly one fifth of the 1,244 inhabitants of the county were African slaves. Mount Moor was established in 1849, 22 years after the New York State Legislature abolished slavery in 1827 and 13 years before President Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863.

James and Jane Benson deeded the land that became Mount Moor Cemetery to William H. Moore, Stephen Samuels and Isaac Williams on July 7, 1849. The land was purchased for the purpose of creating of a non-denominational final resting place for black families that were excluded from cemeteries where whites were buried. The name of cemetery captures the rugged topography of the location and the language of racial exclusion. The property is a wedge-shaped parcel on a steep hill and the term Moor was commonly used in the 18th and 19th century to described people of African descent.

James and Jane Benson deeded the land that became Mount Moor Cemetery to William H. Moore, Stephen Samuels and Isaac Williams on July 7, 1849. The land was purchased for the purpose of creating of a non-denominational final resting place for black families that were excluded from cemeteries where whites were buried. The name of cemetery captures the rugged topography of the location and the language of racial exclusion. The property is a wedge-shaped parcel on a steep hill and the term Moor was commonly used in the 18th and 19th century to described people of African descent.

The area around the cemetery had been, until recently, undesirable marsh land. So much private and commercial refuse was dumped nearby, the site was eventually dubbed Toxic Alley. Lacking the revenue and resources of traditional cemeteries, and with only a meager budget for maintenance, the grounds became overgrown. A lack of complete records and missing headstones have made determination of the exact population of the cemetery impossible.

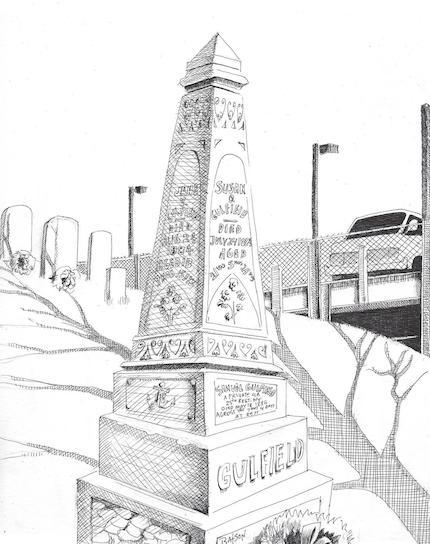

The Gulfields

The cast zinc obelisk monument that is the subject of this week’s sketch is an example of the funerary arts that helped secure Mount Moor a place on the National Register of Historic Places. Also called a catalogue monument, the ornate marker elegantly records evidence of life, death and tragedy. Two of the people buried under the tall metal sculpture died as children, one as a young adult. This is also the resting place of one of the Civil War veterans, Samuel Gulfield, Private Corporal in the 26th Regiment and his wife, Christina.

- Gulfield, Charles P.

4/18/1873 – 8/26/1877 - Gulfield, Christina

1/29/1841 – 3/1/1907 - Gulfield, Jane F

12/9/1870 – 8/24/1884 - Gulfield, Samuel

10/14/1831 – 5/18/1886 - Gulfield, Susan O

2/4/1863 – 7/28/1884

In 1940, a group of leading African American Rocklanders established the Mount Moor Cemetery Association to maintain the burial ground. The first president was Rev. William Clyde Taylor, pastor of Pilgrim Baptist Church. Hezekiah Easter, Jr., who had been elected to the Rockland County Legislature in 1970, became President of the Association in 1977.

Easter’s tenure as President of the Mount Moor Association coincided with the beginning of the battle against over-development chronicled in the documentary film Mega Mall. A Syracuse, New York based developer, the Pyramid Companies, announced their plan to build the second largest shopping mall in America next door to the cemetery in 1985. Using his extensive experience in public office, Easter sought to secure local, state and federal recognition of the historic importance of the site. As a World War II vet, Easter helped coalesce support of his brothers-in-arms to protect and maintain the site. Veterans from every major American conflict are buried in Mount Moor including the Civil War, the Spanish American War, World War I and II and the Korean War.

Even though the Pyramid Companies had amassed their own army of lawyers and public relations specialists to overcome community opposition to the mall, Easter did not relent. Joined by his colleagues Jacqueline L. Holland, Leonard Cooke, Wilbur Folkes, Charlene Dunbar, Bea Fountain and their attorney Alicia Crowe, they group stood their ground, even when confronted by bulldozers and belligerent security guards.

“The families told me they did not want the Pyramid Companies to dig up their ancestors,” said Attorney Crowe. Proposals from the company included burying the plots under 100 feet of soil or disinterring the bodies for reburial elsewhere. “We were not going to allow them to disturb these rightful resting places in order to accommodate more parking spaces,” Crowe recalled.

At a meeting at Depew Manor in 1994, a representative of the Pyramid company surrendered to the group’s demands. Once it was granted a place on the Federal Register, the cemetery could not be buried or dug up. The Pyramid company agreed to construct a fence around the original wedge-shaped survey lines from the 1849 deed, and also agreed to maintain the grounds of the cemetery.

At a meeting at Depew Manor in 1994, a representative of the Pyramid company surrendered to the group’s demands. Once it was granted a place on the Federal Register, the cemetery could not be buried or dug up. The Pyramid company agreed to construct a fence around the original wedge-shaped survey lines from the 1849 deed, and also agreed to maintain the grounds of the cemetery.

There would also be one final tombstone.

On March 13, 2007, Hezekiah Easter, Jr. was laid to rest beside his brother and his father. The man who saved the cemetery is the last man buried at Mount Moor. A parking structure and the facades of box stores loom in the distance, held at bay by a solider and statesman who will forever keep his silent and solemn vigil over these hallowed grounds.

There will be an event in observance of the 150th anniversary of the Civil War at Mount Moor Cemetery on Saturday, April 12 at 1p. Participating organizations include the Sons of Union Veterans of the Civil War, Ellis Camp 124 Department of New York, and the African American Historical Society of Rockland (AAHS) Captain David Smith and representatives of the 26th USCT organization will make remarks. For information contact James Meaney at 917-453-8573

Color photos by Jennifer Rothschild

Special thanks to Brian Jennings, the newly appointed Local History Librarian at New City Library.

An activist, artist and writer, Bill Batson lives in Nyack, NY. Nyack Sketch Log: “Nyack Sketch Log: Our Segregated Cemetery” © 2014 Bill Batson. Visit billbatsonarts.com to see more.