by Bill Batson

The first president of post-apartheid South Africa, Nelson Mandela, died in his Johannesburg home on Thursday of complications from a lung infection. He was 95.

The first president of post-apartheid South Africa, Nelson Mandela, died in his Johannesburg home on Thursday of complications from a lung infection. He was 95.

After 27 years as a political prisoner and 5 years as the African nation’s first democratically elected president, Mandela had withdrawn from public life in recent years.

U.S. President Barack Obama said the world had lost “one of the most influential, courageous and profoundly good human beings that any of us will share time with on this earth”.

According to a somber South African President Jacob Zuma, Mandela will receive a state funeral. Mandela’s service will be on the scale of the late British statesman Winston Churchill and Pope John Paul. As many as five kings, six queens, over 70 presidents and prime ministers and over 2 million faithful are expected to bid the internationally respected leader farewell. President Barack Obama and all living American Presidents that are healthy enough to attend will join the US delegation. This global full house of heads of state is a fitting tribute for a person of Nelson Mandela’s impact and stature.

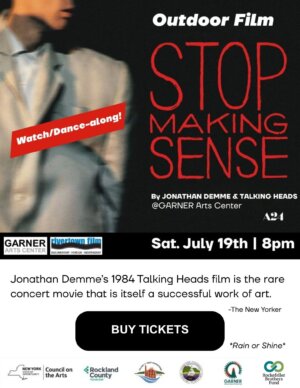

This Nyack Sketch Log was posted in June 2013 in honor of Mandela’s 95th birthday.

In his 1994 autobiography, Long Walk to Freedom, Nelson Mandela chronicles how a black prisoner of a racist white apartheid government became the president of a multiracial nation. But the story of how the book was produced is worthy of its own chapter.

Sketch Log author Bill Batson meeting Walter Sisulu on Robben Island,1994

During my time in South Africa, I got to visit Robben Island, where Mandela was held as a political prisoner from 1963 until 1982 (He spent 82’-88’ at Pollsmoor and 88’–90′ at Victor Verster). On that day, I met two of his former cellmates and leaders in the African National Congress, Walter Sisulu and Ahmed Kathrada. Kathrada described to me the collective process by which portions of the book were written, concealed and smuggled off Robben Island.

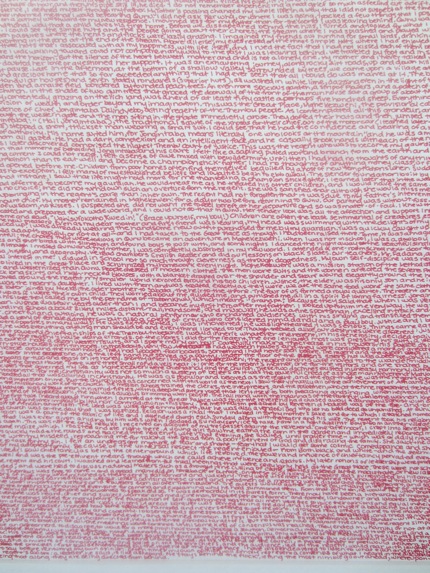

“As the president wrote, he passed on the pages to me for my comments. I then read them to Tata Sisulu; I wrote both our comments and handed them back to the President. He then wrote the final version. This was then handed over to Mac Maharaj (currently the official spokesperson for South African President Jacob Zuma) and Laloo Chiba (who served as a member of Parliament.) These two fellow prisoners then wrote the manuscript in tiny handwriting. I think the 500-600 pages were reduced to 50. These pages were concealed in the covers of an “album” which was constructed by Chiba. Maharaj who was released after twelve years, in 1976, carried the album out of Robben Island and sent it abroad.”

When the original text of the autobiography was discovered by prison authorities in a garden on Robben Island, the punishment was swift and cruel. Mandela, Sisulu and Kathrada lost their access to paper and ballpoints for a period of approximately four years.

Tiny Writing by Alexis Swerdloff

On Mandela’s 80th birthday, I conducted a workshop with students from NYC who reduced the pages of Long Walk to Freedom back into the smallest script possible. Even without the hardships of incarceration, the students struggled to legibly reduce the text to the 10 to 1 ratio that the prisoners accomplished. We mailed our “Tiny Writing Project” to Mandela as a birthday present.

When first published, Long Walk to Freedom revealed previously unknown details about Mandela the lawyer, boxer, military leader and diplomat, but to the surprise of some, he was also an actor.

Robben Island, with Cape Town and Table Mountain in the distance.

“Our amateur drama society made its yearly offering at Christmas. Our productions were what might now be called minimalist: no stage, no scenery, and no costumes. All we had was the text of the play,” Mandela wrote in his autobiography of how he and his colleagues passed their time on Robben Island. “I performed in only a few dramas, but I had one memorable role: that of Creon, the king of Thebes, in Sophocles’ Antigone.”

Apparently, Mandela found the work of Greek playwrights “enormously elevating.” “What I took out of them was that character was measured by facing up to difficult situations and that a hero was a man who would not break down even under the most trying circumstances.”

In the play, King Creon must decide whether or not to give a proper burial to one of his sons, Polynices, who had been killed during a rebellion against his father’s throne. Antigone, Creon’s daughter, rejects her father’s decision and buries her brother. Creon’s response was merciless.

“At the outset, Creon is sincere and patriotic, and there is wisdom in the early speeches when he suggests that experience is the foundation of leadership and the obligations to the people take precedence over loyalty to an individual,” Mandela wrote.

But ultimately, Mandela sided with Antigone. “Creon’s inflexibility and blindness ill become a leader, for a leader must temper justice with mercy. It was Antigone who symbolized our struggle; she was, in her own way, a freedom fighter, for she defied the law on the grounds that it was unjust.”

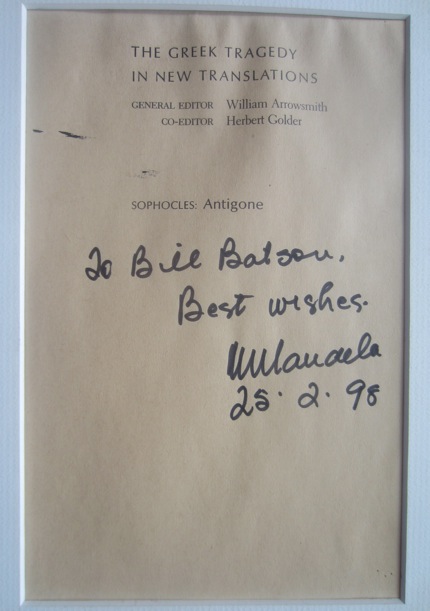

In 1998, on a return trip to South Africa, I shook hands with Mandela on a rope line, but was unable to ask him to sign the copy of Antigone that I had brought with me. The manner in which I eventually got his autograph demonstrates the profound sweep of South Africa’s transformation.

In 1998, on a return trip to South Africa, I shook hands with Mandela on a rope line, but was unable to ask him to sign the copy of Antigone that I had brought with me. The manner in which I eventually got his autograph demonstrates the profound sweep of South Africa’s transformation.

A member of the President’s security team saw the book in my hand and asked me if I wanted Mandela’s signature. The towering bodyguard could have been a body double for Dolph Lundgren. He had the bearing of a seasoned member of the South African Defense Force, which meant that a few short years before he was assigned to protect President Mandela, he was part of a government determined to hold him captive, and extinguish his dream of South African multiracial democracy. He may have even served as a guard on Robben Island.

Three months after the anonymous security official made his unsolicited and magnanimous offer, I received Mandela’s autograph on my copy of Antigone in the mail.

A friend who lives in South Africa held her breath each time she saw or heard Mandela’s name on the news in recent months. Another friend, who met Mandela in New York during his 1990 visit, which included an incredible Yankee Stadium rally and a ticker tape parade, is bracing for the loss of his leadership in the world. “He gives us our moral center,” she declared.

Bill Batson is an activist, artist and writer who lives and sketches in Nyack, NY. Nyack Sketch Log: Nelson Mandela 1918-2013: Full House of Kings, Queens and Presidents to Attend Funeral ” ©: 2013 Bill Batson.

The Nyack Sketch Log is sponsored by The Corner Frame Shop at 40 South Franklin Street in Nyack, NY.