The Story of the Tragic Van Houten Livery Fire

The winter of 1893 was bitterly cold. By January 18, the Hudson River had long since formed its ice bridge, deep snow blanketed the village, and a biting wind made it seem even colder. Hidden away at the corner of Church and Liberty Streets, a fire broke out shortly after midnight at the Van Houten Livery. The youthful night watchman immediately sounded the alarm. Firemen rushed to the scene, but despite their heroic efforts, eighteen of twenty-one horses perished.

Not only did the uninsured Van Houten brothers lose their handsome stable, but they and the villagers also lost true animal companions.

“Horses were not only valuable property, but also held in sentimental regard, so that Nyack was almost as shocked by the loss as if human lives had been involved.”

Virginia Parkhurst, Nyack Fire Department, 125th Celebration, 1988

Undeterred by the devastating loss, the Van Houten brothers rebuilt an even larger livery, which was soon consumed by the rise of the automobile. The tragedy at the Van Houten Livery stood at the crossroads of history and change.

Gilded Age Liveries

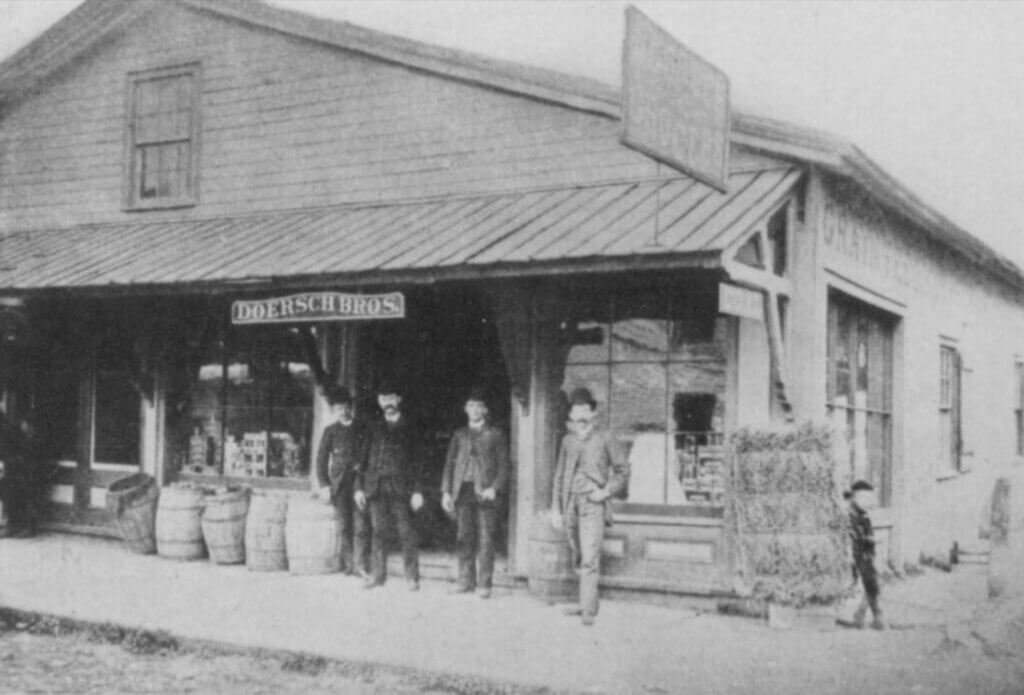

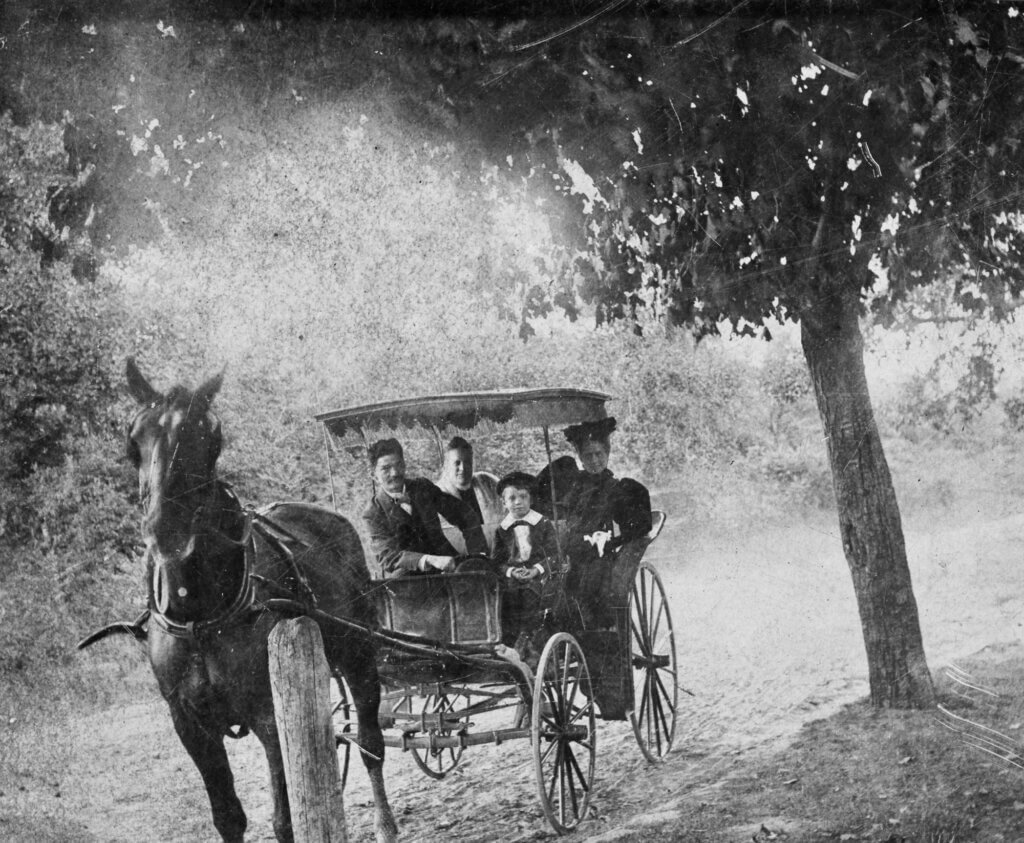

Livery stables in Nyack, New York, were integral to the community during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. They provided essential services such as horse boarding, rentals, and transportation. Travelers arrived in carriages or on horseback to stay at Nyack’s resort hotels, including the downtown Hotel St. George and South Nyack’s Prospect House. Businesspeople and visitors arriving by steamboat or train relied on liveries for transport. Villagers who could afford a horse, like Dr. J. E. Giles, boarded their animals there, confident in the quality of care they would receive.

1890s photo showing the Nyack docks with carriages being loaded with summer guests bound for Mont Lawn. The steamboat appears to be the Chrystenah. The Nyack Rowing Association clubhouse is on the right. Courtesy of the Nyack Library.

Livery fires were common in Nyack and beyond. These stables stored vast amounts of hay, oats, straw, and other highly combustible materials. Although Nyack had electricity at the time, most lighting consisted of gas lamps, and heating relied on wood or coal stoves. Adding to the danger, rumors circulated that an arsonist haunted the village, a claim fueled by persistent gossip. Following the fire, the village board voted to hire a fire marshal to investigate.

The Van Houten Brothers

Edward G. Van Houten (1836-1894) and his brother Erastus (1837-1899) came from an old Rockland County Dutch family. Both were born on their parent’s New City farm. Edward began working in a Haverstraw hardware store at an early age and later delivered mail, like his father. He moved to Nyack in 1861 and partnered with M. H. Jersey to open a butcher shop on Broadway near Burd Street. He also worked in real estate and served as the village Justice of the Peace until his death.

Erastus arrived in Nyack as a young man and, like his brother, worked as a butcher, possibly at Edward’s shop. In 1871, the two brothers partnered to build the Van Houten Livery. Erastus’ first wife died young, and he later remarried. His family lived on Franklin Street before moving to a home on Spear Street, not far from the Nyack Rowing Association clubhouse.

Both brothers are buried in Oak Hill Cemetery.

A Brief History of the Location

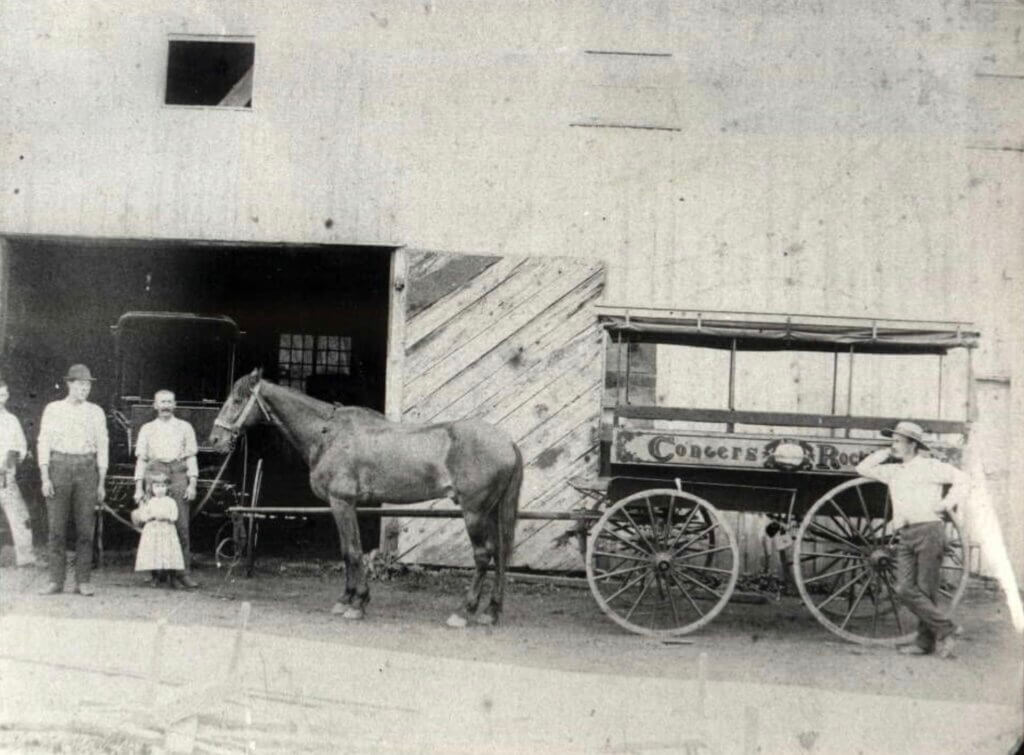

The site of the Van Houten Livery holds a remarkable place in Nyack’s history. The lot became a place of business in 1852 when D. D. Demarest partnered with Tunis to operate a lumber yard and dry goods store. In 1868, A.L. Christie absorbed much of this business when he created the Wigwam, a meeting hall with a grocery facing Broadway. In 1871, Erastus and Edward G. Van Houten opened their livery at the rear of the Wigwam just across Liberty Street from Christie’s Sleigh and Carriage Shop. The corner of Church and Liberty became a one-stop location for horses, carriages, sleighs, and related services.

Later, the Broadway Theater opened at the front of the old Wigwam and eventually expanded to absorb the livery. In the 1940s, the Tappan Zee Playhouse replaced the closed Broadway Theater. The theater’s backstage and dressing room occupied the old livery space. By 2004, the theater complex had disappeared, and urban renewal absorbed the once-busy intersection of Liberty and Church Streets.

The Livery

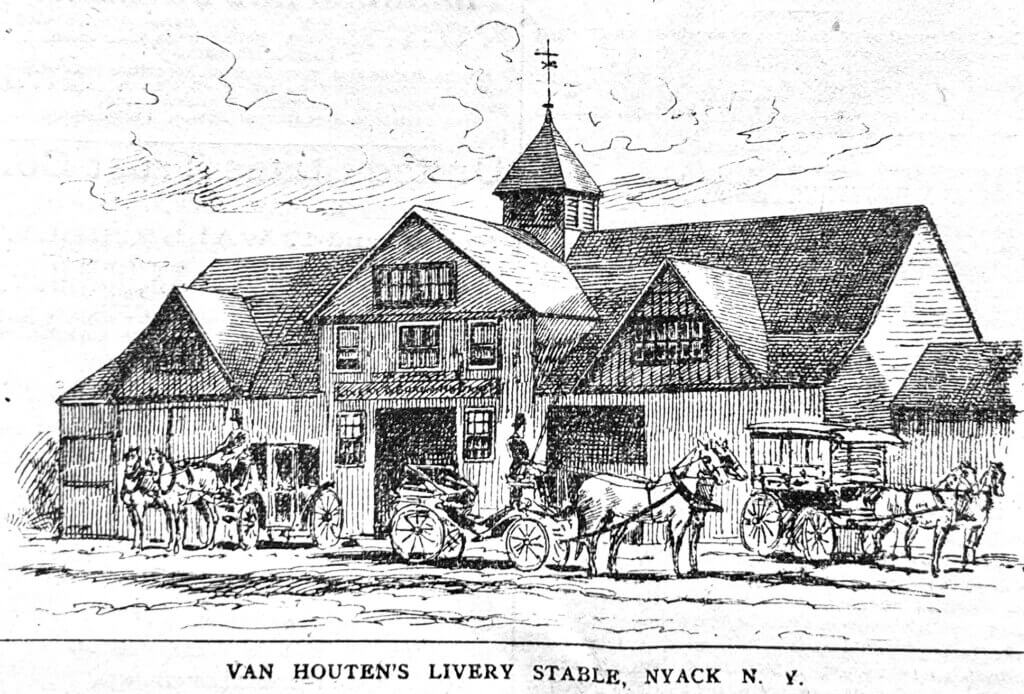

The Van Houten Livery was a handsome two-story structure with a peaked ventilator topped by a weathervane. Horses occupied stalls on the ground floor alongside carriages and buggies. A single door fronting Church Street provided access.

The livery was such an architectural landmark that a July 2, 1889, Daily Graphic article titled “Nyack—The Naples of America” highlighted it as one of Nyack’s most important buildings. Established in 1871, it was by far the largest livery in town. Known for their expertise, the Van Houtens served patrons with promptness and reasonable rates.

Livery Arson?

Villagers suspected an arsonist at work due to the frequency of fires. Although only one case of arson was ever proven—when a firefighter started a blaze at the Old Village Hall (now the Hudson House restaurant)—Nyack experienced four livery fires in four years. Just twelve days before the Van Houten Livery fire, flames engulfed David Kessler’s stable on Bridge Street.

On January 11, 1893, Kessler’s night watchman awoke to the sound of horses stamping. Smoke filled the stable. Instead of immediately sounding the alarm, he ran to Kessler’s house in South Nyack, delaying the firefighters’ response. By the time Nyack’s night watchman, Police Officer Tobias Justrich, discovered the fire and raised the alarm, the structure was fully ablaze.

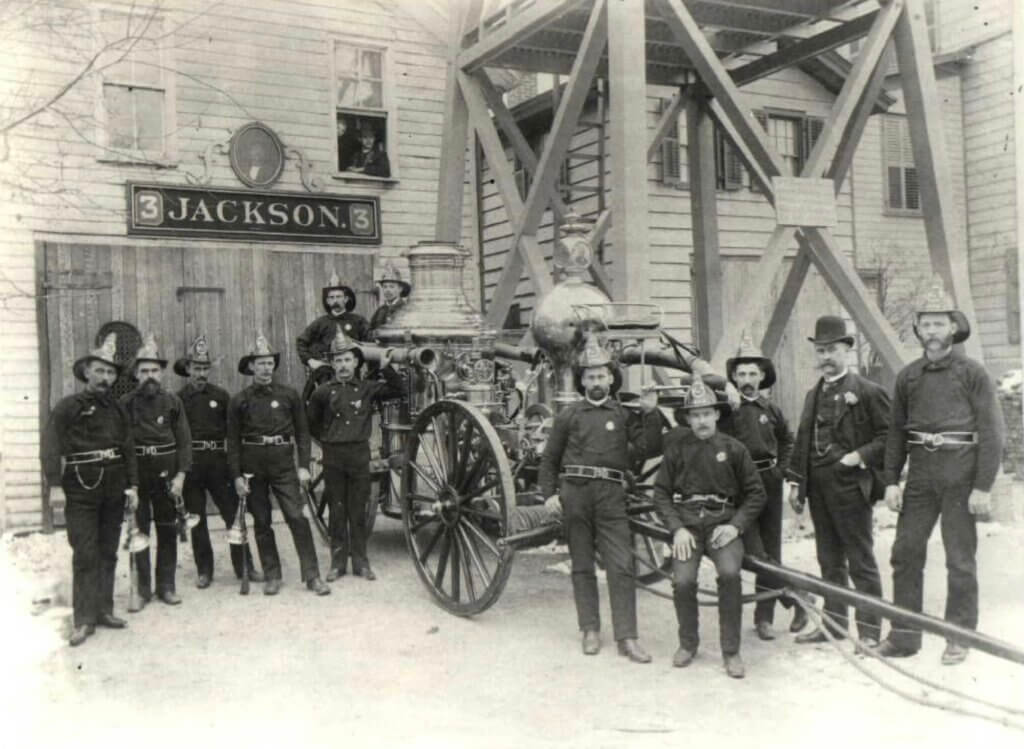

Arriving firemen from Jackson No. 3 watched in horror as terrified horses ran through the burning building. None could be coaxed outside. Four horses died, but one white horse miraculously survived in its stall, wild with fright.

After the fourth fire, the Rockland County Journal reported that a “firebug” might have been responsible for the recent stable fires.

The Van Houten Fire

Erastus Van Houten left the stable at 10 p.m. on the night of the fire. Charlie Vanderbilt, a young boy who slept in the stables as a watchman, sat by the office stove waiting for a late-arriving horse to cool down before watering him. At 12:30 a.m., he walked to the rear of the stables and was startled to see flames rising from bags of feed and hay.

He tried to douse the fire with buckets of water, but it spread too quickly. He ran to the nearby telephone building to raise the alarm. Nyack’s infamous “mockingbird” fire alarm shrieked into the night. Firefighters from Jackson Hose Company, Mazeppa, Upper Nyack Empire Hook and Ladder, and Chelsea Company battled sub-zero temperatures, fierce winds, and deep snow. Streams of water from steam-driven pumps fought the blaze while the agonized cries of dying horses echoed through the night.

Of the twenty-one horses in the stable, only three survived. Sixteen died in their stalls. The next morning, the scene was apocalyptic—gutters frozen with water, charred ruins draped in icicles, and the grim sight of dead horses. Hundreds of villagers gathered to mourn the loss. Even the stable dog wandered among the ruins in grief.

Local newspaper headlines on January 18, 1893

A New Livery

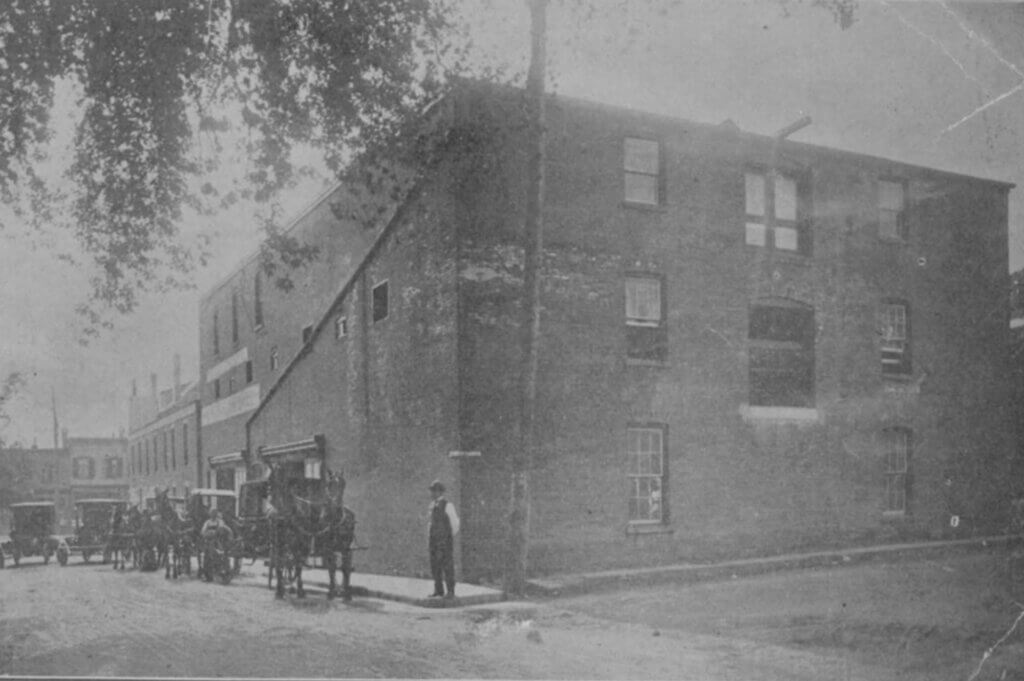

Despite the devastating loss, the Van Houten brothers rebuilt almost immediately, reopening on July 15, 1893. Their new three-story, 80-by-50-foot livery housed horses on the second floor, accessed by a grooved ramp. An elevator transported carriages to long-term storage on the third floor. They opened with twenty-nine horses and room for more.

Though neither brother lived to see the turn of the century and the advent of the automobile, their legacy endured. Villagers never forgot the terror of that night of ice and fire or the tragic loss of such loyal and dependable animals.

Mike Hays has lived in the Nyacks for 38 years. A former executive at McGraw-Hill Education in New York City, he now serves as Treasurer and past President of the Historical Society of the Nyacks, Trustee of the Edward Hopper House Museum & Study Center, and Historian for the Village of Upper Nyack.

Since 2017, he has written the popular Nyack People & Places column for Nyack News & Views, chronicling the rich history, architecture, and personalities of the lower Hudson Valley. As part of his work with the Historical Society, Mike has researched and developed exhibitions, written interpretive materials, and leads well-attended walking tours that bring Nyack’s layered history to life.

Married to Bernie Richey, he enjoys cycling, history walks, and winters in Florida. You can follow him on Instagram as @UpperNyackMike.

Editor’s note: This article is sponsored by Sun River Health and Ellis Sotheby’s International Realty. Sun River Health is a network of 43 Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHCs) providing primary, dental, pediatric, OB-GYN, and behavioral health care to over 245,000 patients annually. Ellis Sotheby’s International Realty is the lower Hudson Valley’s Leader in Luxury. Located in the charming Hudson River village of Nyack, approximately 22 miles from New York City. Our agents are passionate about listing and selling extraordinary properties in the Lower Hudson Valley, including Rockland and Orange Counties, New York.