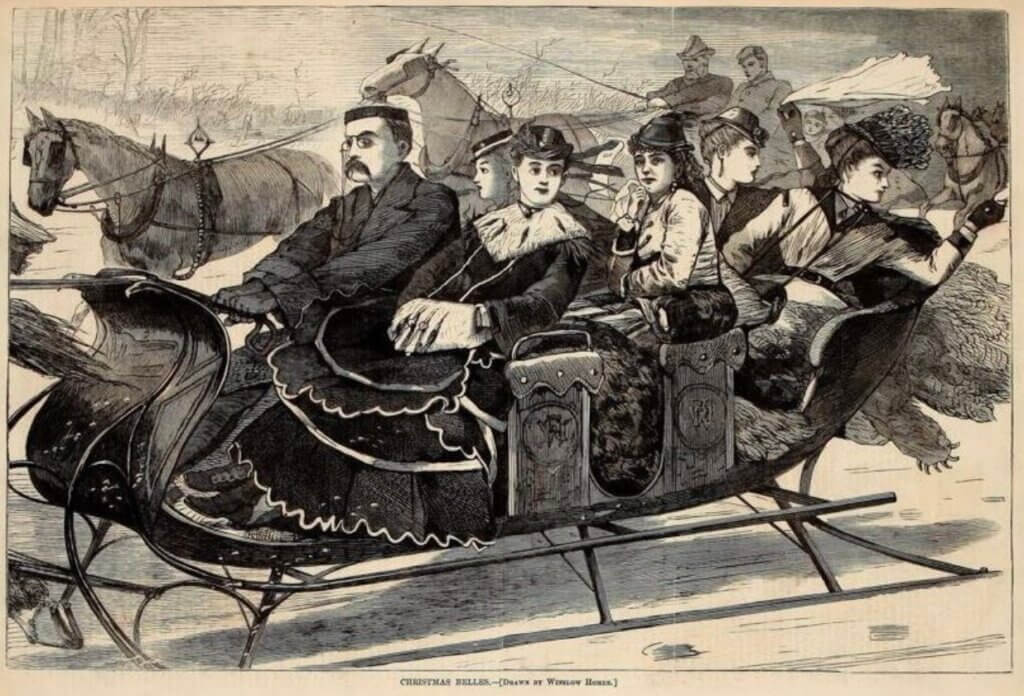

Long before SUVs and all-wheel-drive cars appeared, Nyack’s residents relied on horse-drawn, locally made sleighs to navigate the village’s steep, unplowed winter roads. These 19th-century sleighs looked nothing like the sentimental versions featured in “Sleigh Ride,” “Winter Wonderland,” or “Jingle Bells.” They came in many shapes and sizes.

“Sleigh runners gripped the ice while carriage wheels skated off the road.”

Winter roads were almost never plowed in the 19th century. Sleighs weren’t a luxury. They were survival gear.

By the late 1800s, Nyack factories produced shoes, pianos, and boats. Less known is that two Nyack sleigh makers supplied handmade sleighs—ranging from simple one-horse cutters to ornate European-style models seating eight plus a coachman—to customers nationwide.

Every sleigh was handmade—carved, painted, trimmed, and upholstered by skilled Nyack craftsmen.

What Sleighs Were Used For

Sleighs were more than winter fun; they moved people, goods, and even commuters. Businesses relied on stout, toboggan-like work sleighs called “pungs” to haul baked goods, logs, and blocks of ice. In New York City, large four-horse sleighs even served as winter commuter vehicles along Broadway.

Kids and “Hooking Pungs”

Children turned pungs into games—“hooking pungs” meant grabbing the runners as they passed and hitching a free ride. It was the ultimate Nyack snow-day thrill.

Why Sleighs Beat Carriages

Because few roads were plowed in winter, wheeled carriages often skidded off icy surfaces. Metal runners gripped the ice more reliably, making sleighs the safer and more practical choice for winter travel.

Accessories & Sounds of Winter

Sleigh and carriage makers shared similar skills, so many shops built both and stayed busy year-round. Sleighs often came with accessories—custom paint, decals, colorful plumes, lights, and sleigh bells. East Hampton, CT, known as “BellTown,” supplied most of the bells ringing through Nyack winters. Bells weren’t just decorative; they warned pedestrians and other drivers of a sleigh’s approach.

Dangers on the Road

Warnings mattered. Sleighs were difficult to turn and nearly impossible to stop quickly, and accidents were common. In 1888, runaway horses pulling the Niederhauser Bakery sleigh flipped as they turned from Main Street onto North Broadway, shattering a nearby window.

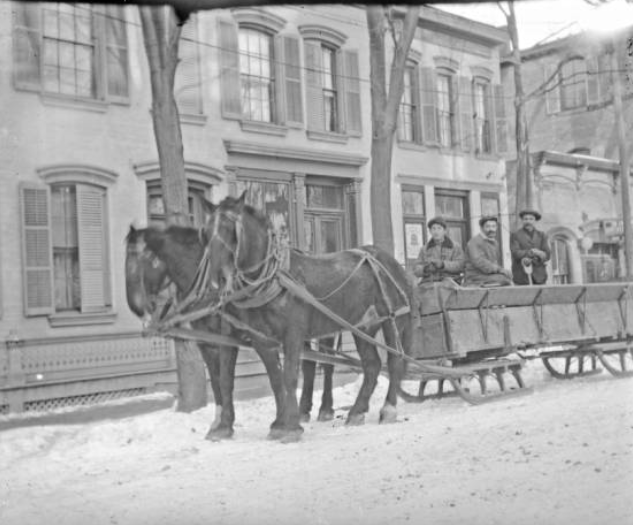

A sleigh halts in front of 287 S. Broadway. Courtesy of the Nyack Library.

Sleigh Styles

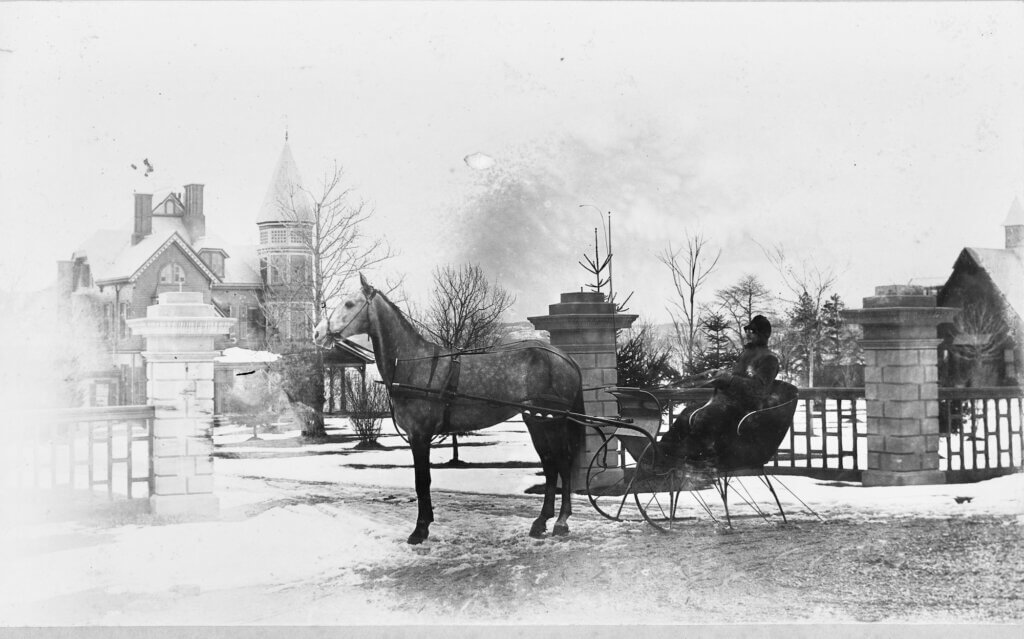

The simplest and cheapest sleighs featured a single seat board. The Portland Cutter—a light, durable design—was the most popular. But as Gilded Age tastes shifted, wealthy clients demanded sleighs that imitated stylish carriage bodies. Designers responded with sleighs modeled on cabriolet, phaeton, and curricle carriages. A second design trend drew on Russian and German styles, with elaborate curves, embossed panels, and luxurious trim.

Nyack’s sleigh makers excelled at custom work. They produced unique models tailored to wealthy buyers across the country. William Hand, owner of the Ross-Hand Mansion on Franklin Street, ordered a grand eight-passenger sleigh from the Christie Brothers for $85.

For most of the 19th century, Nyack’s two sleigh factories turned out models for both local customers and national distributors. Other Nyack firms handled painting, servicing, and repair work.

Ads in the Rockland County Journal for the two Nyack sleigh makers.

The Wright Factory

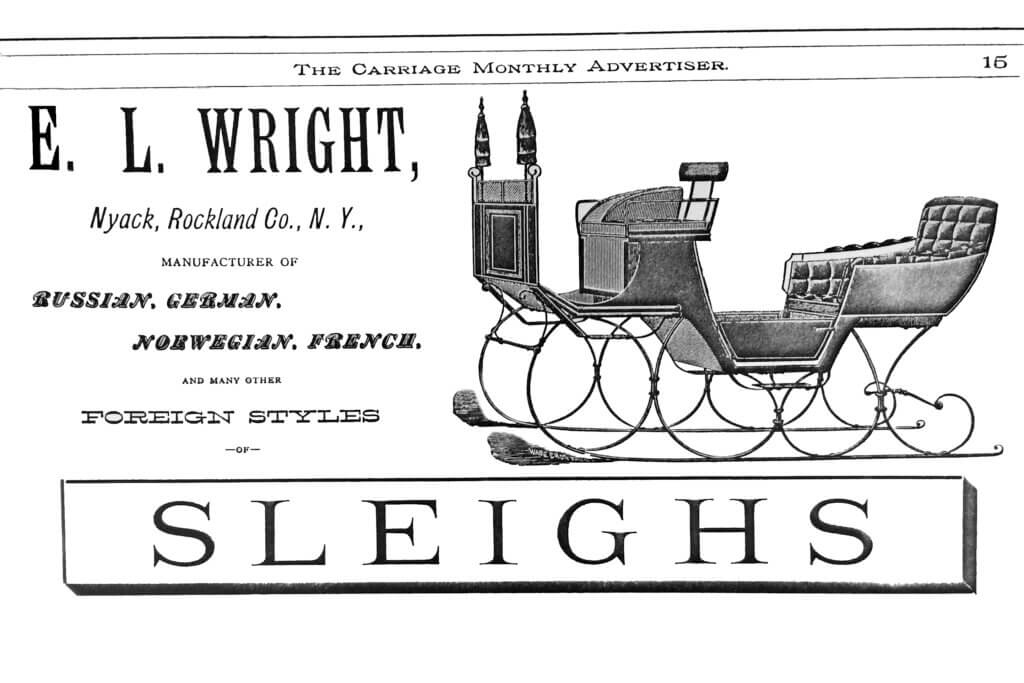

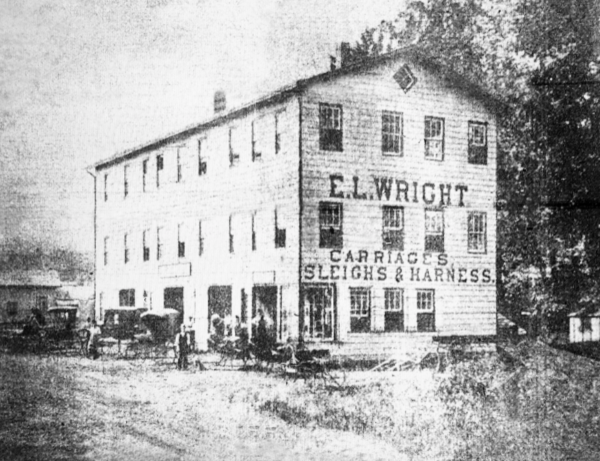

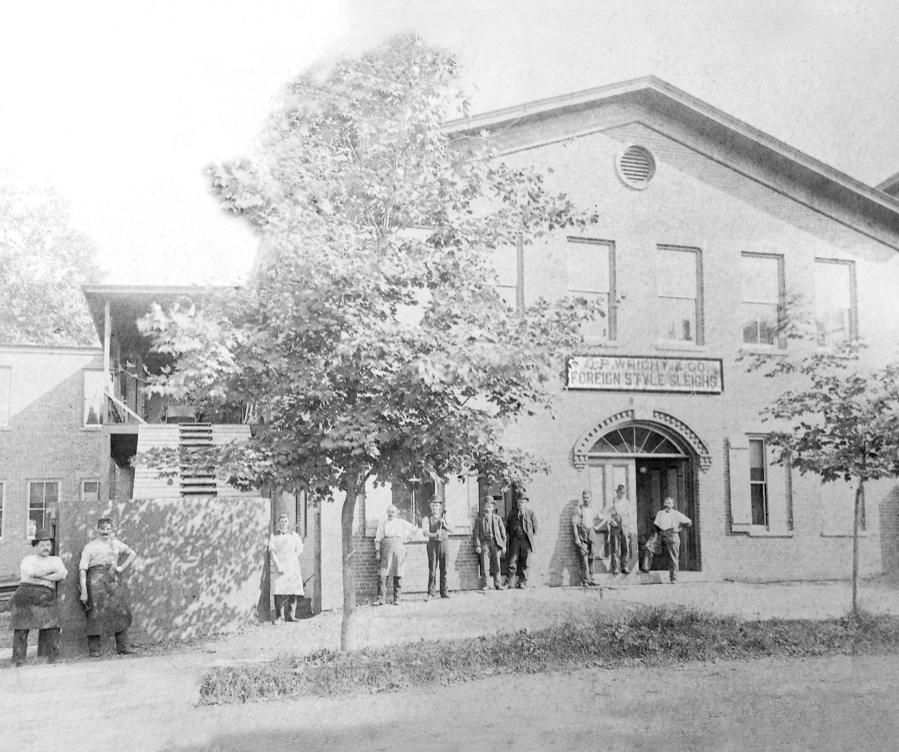

E.L. Wright began producing carriages, wagons, harnesses, and more than 27 sleigh varieties in 1843. He built a three-story wood-frame shop at Hudson and Railroad Avenues (now Depot Place), next to Nyack Brook.

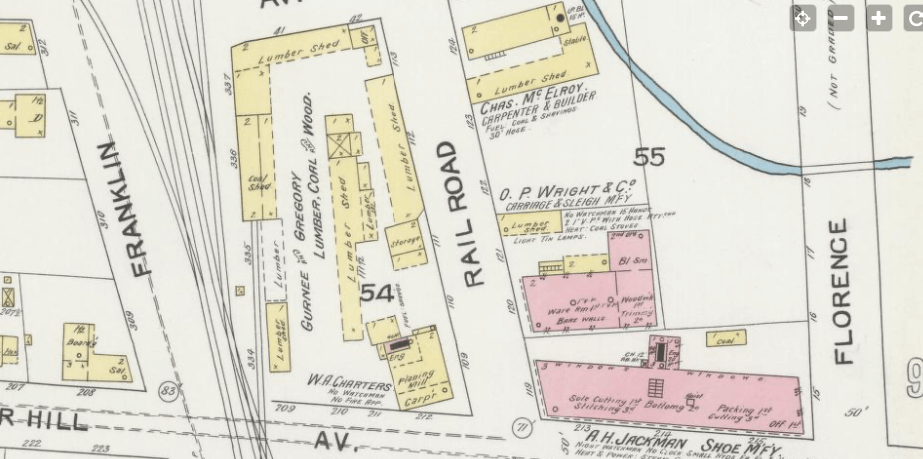

Its location across from the train station made shipping sleighs easy. The original shop burned in the 1880s. Wright’s son, Ornan P. Wright, replaced it with a new brick factory in 1887.

The Wright factory location in 1896 across from the Gregory & Sherman lumber company and between a shoe factory and McElroy’s carpentry shop. The entire area is now the site of Pavion apartments.

O.P. Wright’s designs frequently appeared in Carriage Monthly, a national trade magazine. One of his most admired creations was a Russian six-seat vis-à-vis sleigh with carved tiger-head panels, ultramarine-blue paint striped in light blue, plush blue cloth trim, diamond-plaited cushions with fancy buttons, and rugs of blue wool with red stripes.

In 1877, the Rockland County Journal visited the shop and found five new pony sleighs ready for a Brewster, NY, customer. The reporter praised their design, paintwork, and fine trimming.

The Christie Factory

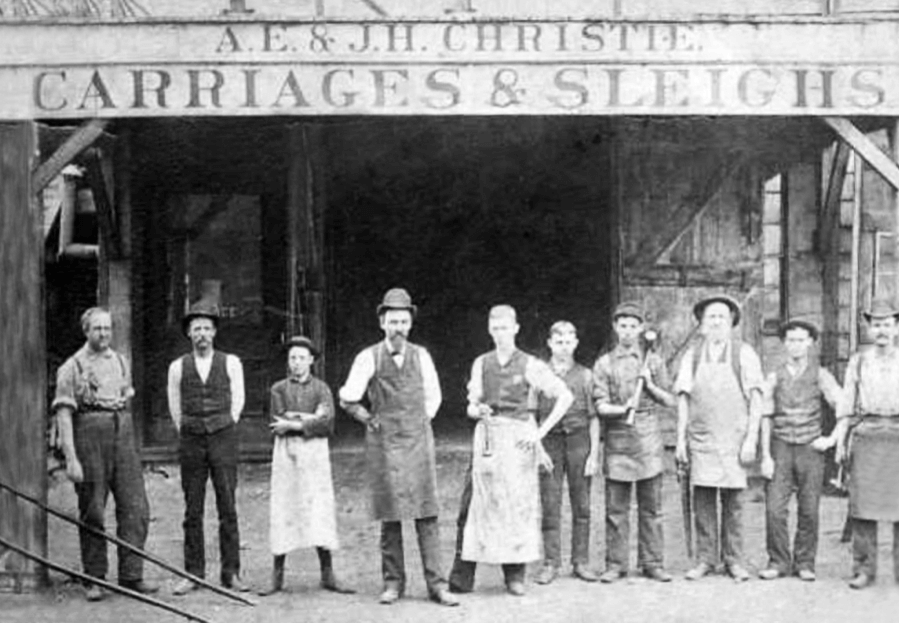

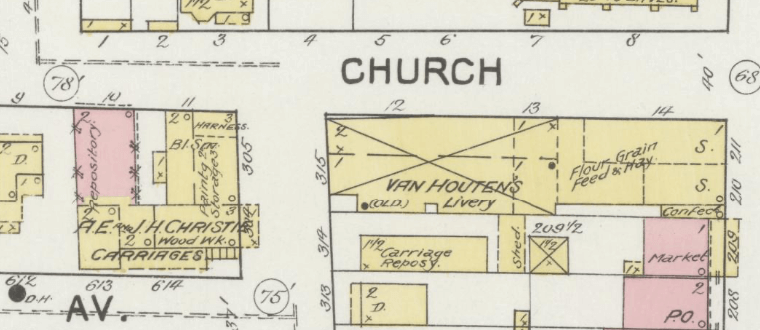

Aaron Christie opened Nyack’s first carriage and sleigh shop in 1835 at Liberty and Church Streets. He lived nearby on Broadway next to the First Presbyterian Church (now the Nyack Center). A town water pump—known locally as the Christie Pump—stood in front of his house. Several trades clustered at the Christie works: a harness maker, carriage trimmer, blacksmith, wheelwright, and painters.

Christie’s sleigh and carriage factory once filled an entire block on Liberty Street.

Christie’s sons, Augustus E. and James H., expanded the operation in 1871, forming A.E. & J.H. Christie, makers of fine carriages and sleighs. They, too, sold nationally and advertised in Carriage Monthly, offering elaborate six-passenger Russian sleighs

The End of the Sleigh Era

The need for sleighs faded quickly once automobiles appeared on Nyack’s streets. By 1903, the Wright factory on Depot Place had already become a box-making plant. The Christie carriage works on Liberty Street lasted a few more years but closed around 1910 after seventy-five years in business. Their buildings took on new purposes as the tools and patterns that once shaped winter travel disappeared from daily use.

For more than half a century, Nyack’s sleigh makers served both local customers and a national market, sending custom models as far as New England and the Midwest. At home, their sleighs defined winter life—gliding down North Broadway, hauling goods from the riverfront, and filling snowy streets with the sound of bells.

The arrival of the motor age changed everything. But for a remarkable era, Nyack’s craftsmen shaped how people moved through winter, creating a small but memorable industry that blended practicality, ingenuity, and local skill.

Mike Hays has lived in the Nyacks for 38 years. A former executive at McGraw-Hill Education in New York City, he now serves as Treasurer and past President of the Historical Society of the Nyacks, Vice President and Trustee of the Edward Hopper House Museum & Study Center, and Historian for the Village of Upper Nyack.

Since 2017, he has written the popular Nyack People & Places column for Nyack News & Views, chronicling the rich history, architecture, and personalities of the lower Hudson Valley. As part of his work with the Historical Society, Mike has researched and developed exhibitions, written interpretive materials, and leads well-attended walking tours that bring Nyack’s layered history to life.

Married to Bernie Richey, he enjoys cycling, history walks, and winters in Florida. You can follow him on Instagram as @UpperNyackMike.

Editor’s note: This article is sponsored by Sun River Health and Ellis Sotheby’s International Realty. Sun River Health is a network of 43 Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHCs) providing primary, dental, pediatric, OB-GYN, and behavioral health care to over 245,000 patients annually. Ellis Sotheby’s International Realty is the lower Hudson Valley’s Leader in Luxury. Located in the charming Hudson River village of Nyack, approximately 22 miles from New York City. Our agents are passionate about listing and selling extraordinary properties in the Lower Hudson Valley, including Rockland and Orange Counties, New York.