The Blizzard of 1888 and the Storm That Stopped New York

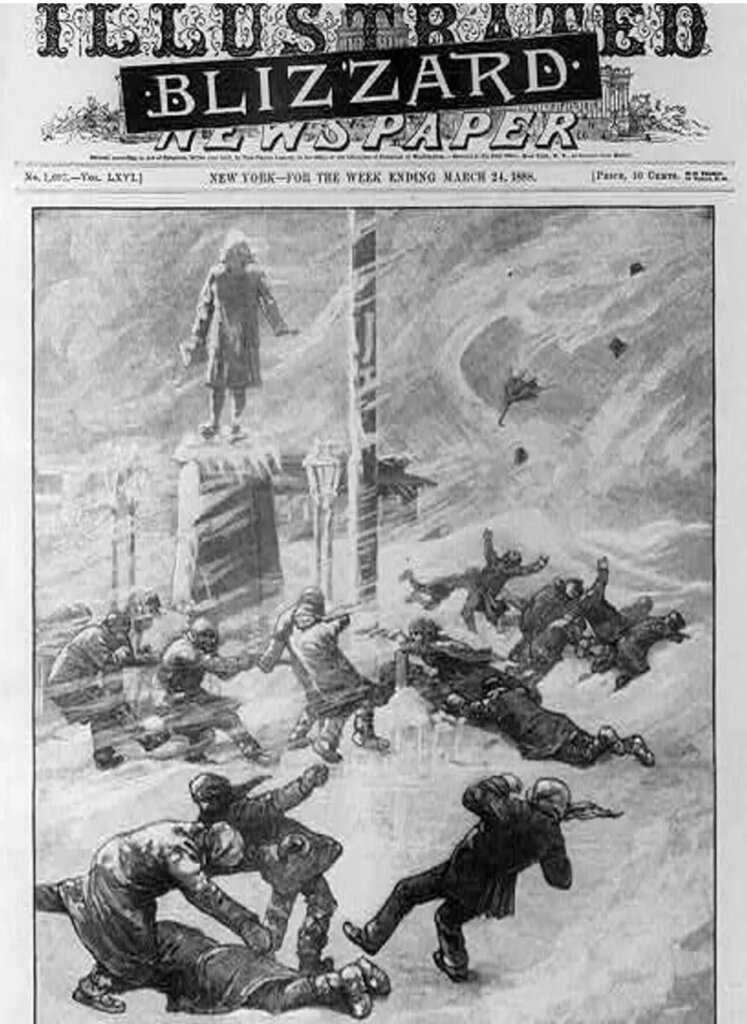

A little after midnight on Monday, March 12, 1888, steady rain turned to sleet and then to heavy, wet snow driven by fierce winds. No forecast warned of what was coming. By dawn, one of the most destructive winter storms in American history had brought daily life to a standstill from Washington D. C. to New England.

Today, terms like bomb cyclone and polar vortex dominate weather coverage. In 1888, people had no such language and little warning. Wall Street financiers, dockworkers, shopkeepers, and a six-year-old Edward Hopper in Nyack all woke to the same reality: the region had disappeared under snow.

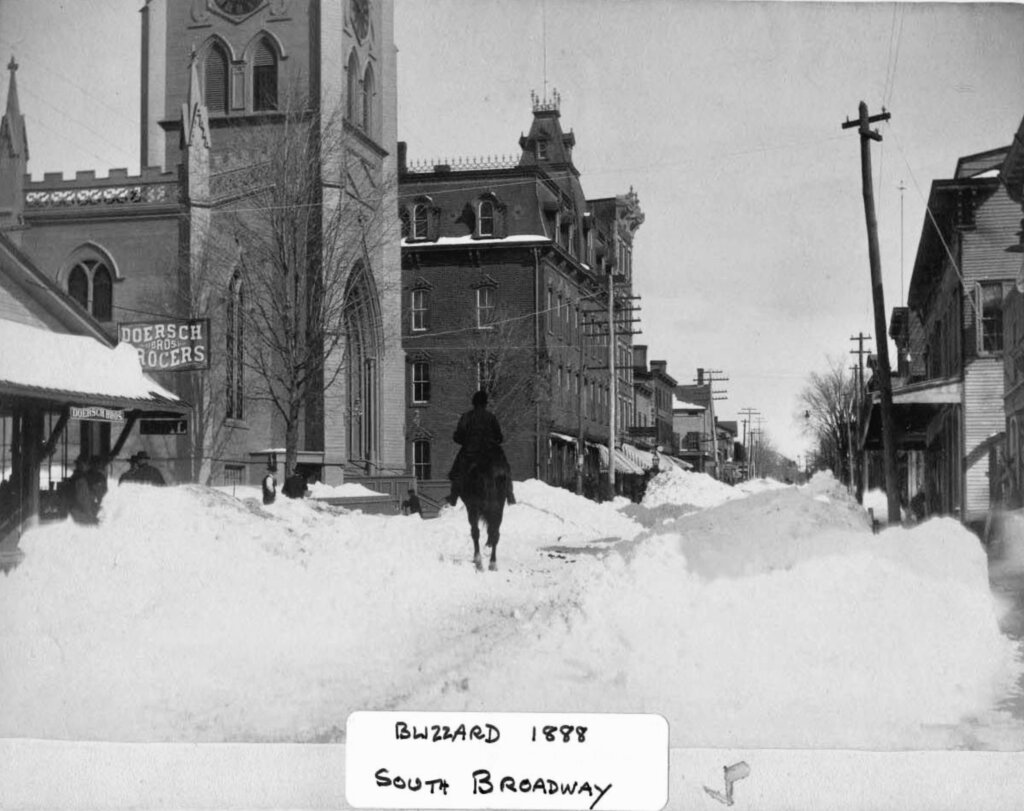

The town pump stands at the center of the street. One of the brick buildings on the left housed the Nyack Post Office. Urban renewal later removed these structures, and the site is now occupied by Tallman Towers. Courtesy of the Nyack Library.

A City and a Village Under Siege

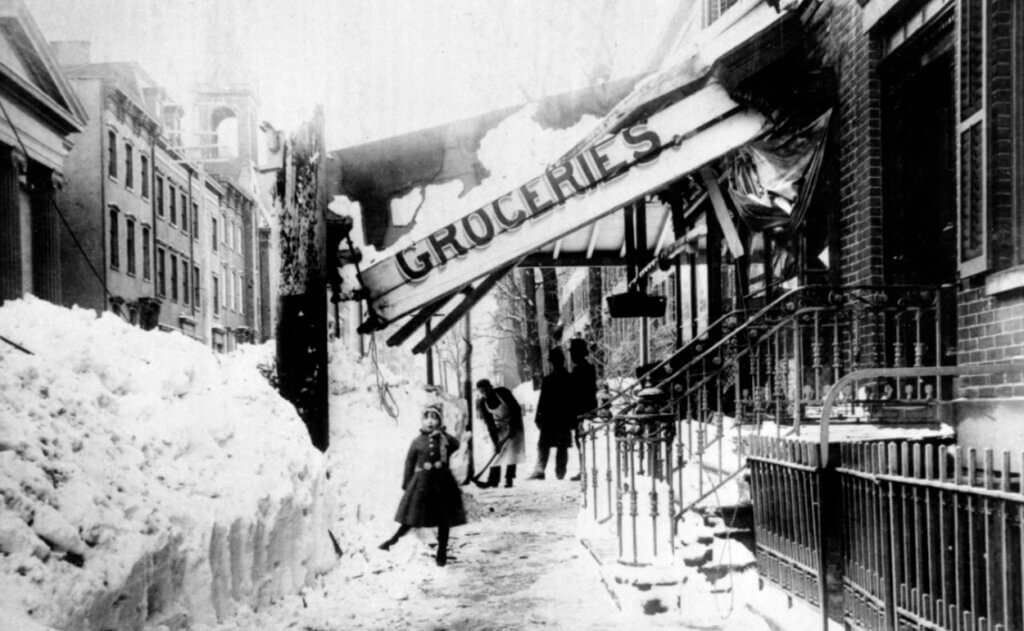

In Nyack, as in New York City, the wind battered doors and froze shutters in place. Snow plastered building facades and packed streets. Walking became dangerous, especially for women weighed down by long skirts. Milk wagons could not move. In a village of about 4,000 people, residents purchased 879 cans of evaporated milk in a single day.

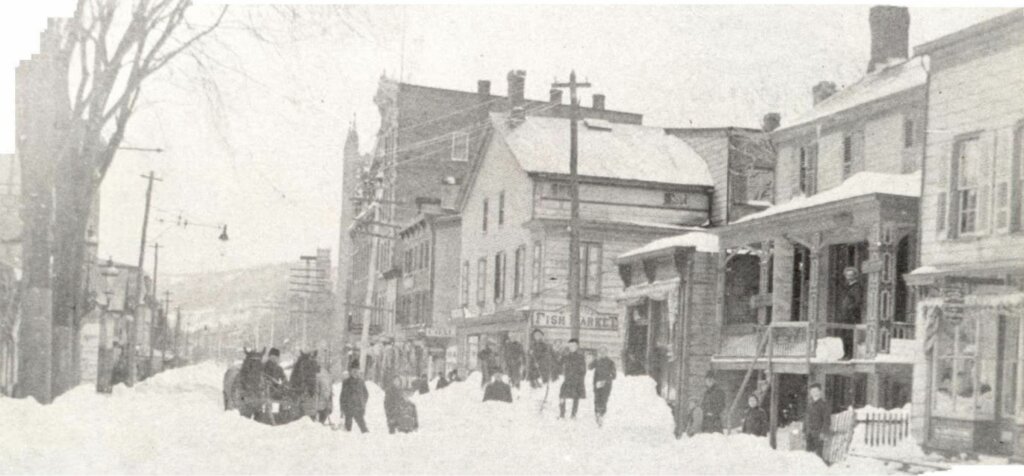

Unplowed streets in Nyack following the Blizzard of 1888.

Hotel St. George appears on the left, while Piermont Avenue is shown on the right at its intersection with Remsen Avenue. Deep snow and the absence of organized clearing equipment brought travel to a halt. Courtesy of the Nyack Library.

The storm’s scale made it unforgettable. Later generations would rank the Great Blizzard of 1888 as the worst winter storm in U.S. history, not only for snowfall but for how much of the population it affected. Surface transportation collapsed in Boston and New York. That failure directly accelerated the push for underground subways and buried utility lines. It also became the first large disaster extensively documented by photography. The images leave little doubt about the storm’s severity.

The Blizzard That Changed American Cities

The Blizzard of 1888 shut down transportation and communication across much of the Northeast. Railroads stopped, ferries froze in place, and telegraph lines failed. In New York and Boston, the breakdown of surface transit led directly to the construction of underground subways and the burial of utility lines. The storm also marked the first time a natural disaster was widely documented through photography, shaping how Americans understood weather related risk and urban vulnerability.

The “Great White Hurricane”

Meteorologically, the storm behaved unlike anything people had experienced. A warm, moisture-laden system from the south collided with an Arctic front from Canada, forming a powerful nor’easter. As it passed New York, the storm stalled, looped back on itself, and intensified.

Temperatures dropped fast. Two days before the storm, readings reached the 50s. Snow began falling around 1 a.m. on March 12. By morning, winds reached 50 miles per hour. The temperature fell to 24 degrees that day and dropped to 6 overnight, still a record for March 12. Snow ended Monday evening, but the wind did not.

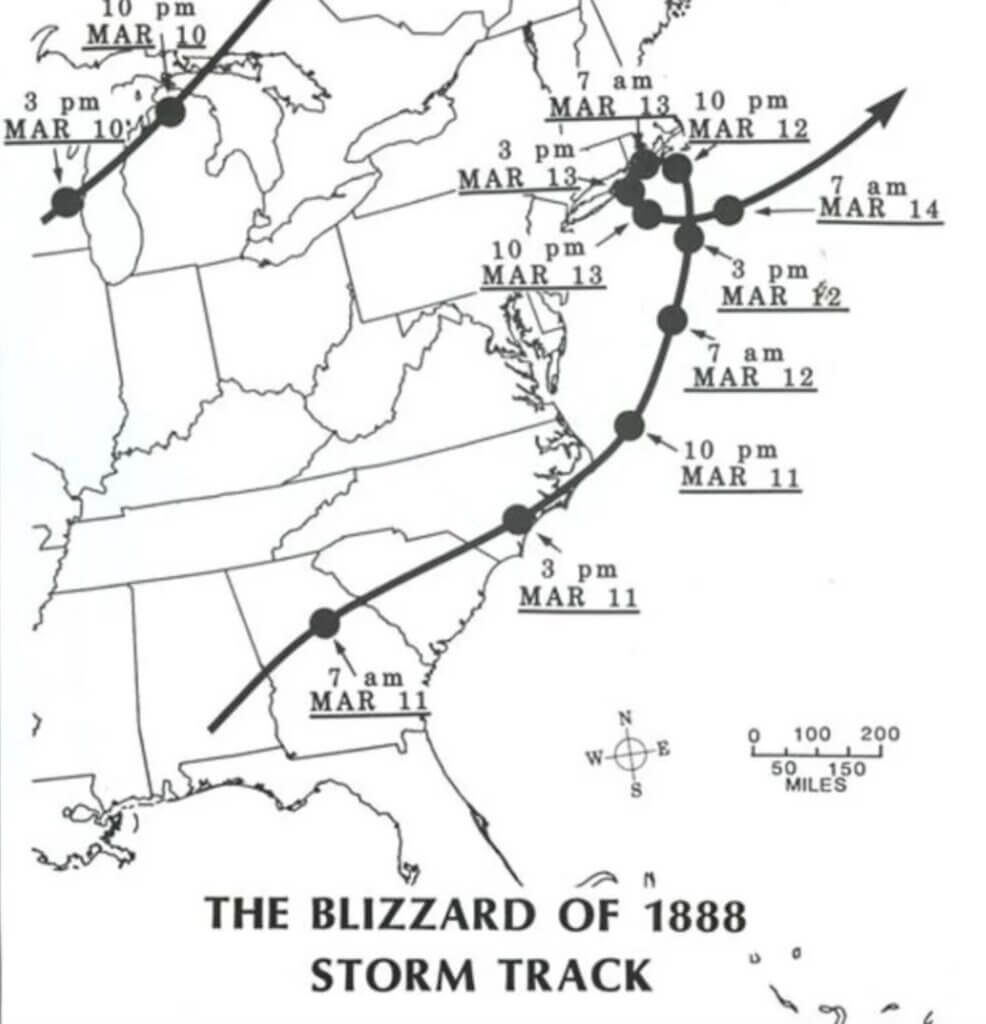

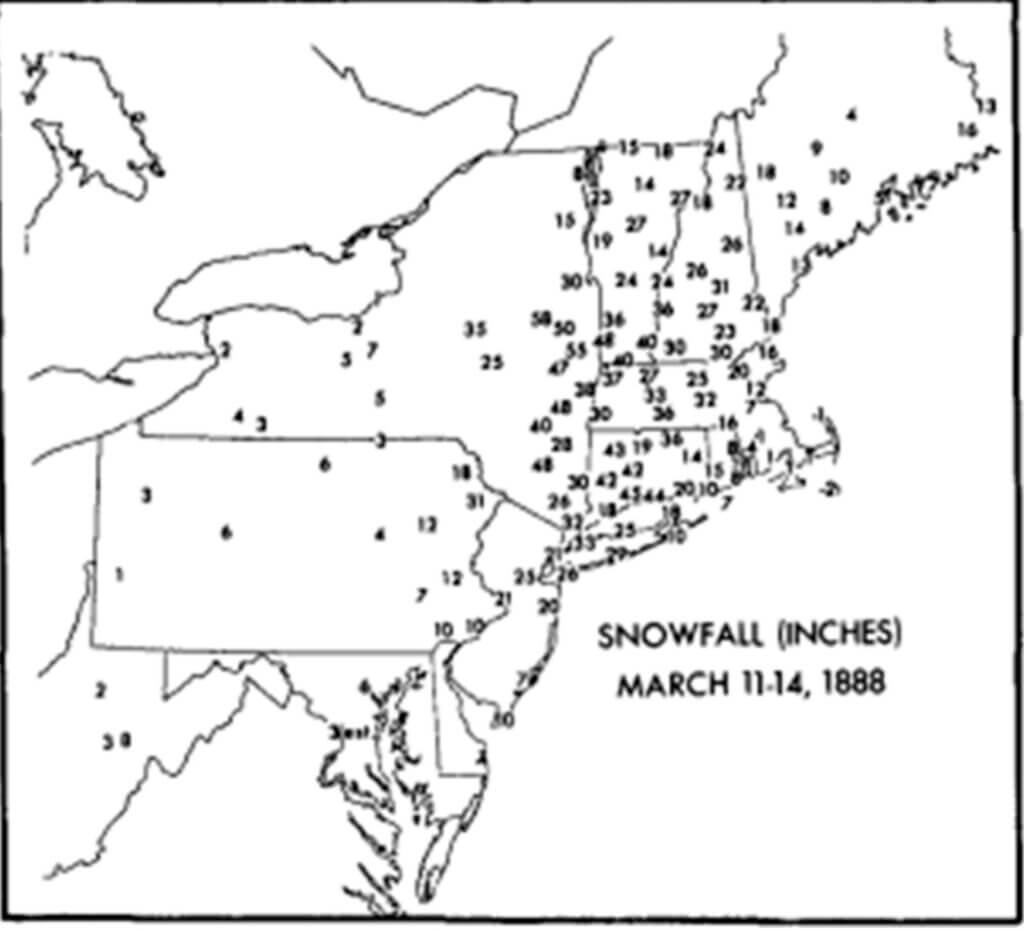

Maps of the Blizzard of 1888 track and snowfall totals.

The storm followed an unusual looping path along the Atlantic coast, while extreme snowfall accumulated across the Hudson Valley and interior regions.

Snowfall totals varied wildly. Central Park recorded 21 inches. Parts of Brooklyn and Queens measured three feet. Saratoga Springs reported 56 inches. In some locations, the wind scoured streets bare. Elsewhere, it built drifts as high as forty feet, including one measured in Dutchess County.

Along the coast, the storm proved just as deadly. Rough seas wrecked or grounded roughly 200 ships between the Chesapeake Bay and Canada. Even sheltered harbors saw vessels sink.

New York City Shuts Down

Roughly 200 people died in New York City. Among them were Henry Bergh, president of the ASPCA, and Roscoe Conkling, one of the nation’s most prominent Republican leaders. Conkling attempted to walk home from Wall Street, collapsed in the snow, and died a week later.

Transportation failed across the city. Trains, streetcars, ferries, cabs, and mail service all stopped. Telegraph lines went down. Communication with other cities vanished. The disruption felt absolute, much like a modern city losing the internet overnight.

Hotels filled beyond capacity. Astor Place laid out 200 cots. Banks housed employees overnight in single rooms. Passengers stranded on trains burned wood from seats and card tables to keep warm. Most theaters closed, though Daly’s Theater staged A Midsummer Night’s Dream for a small audience using stand-ins for missing actors. Barnum’s circus performed at Madison Square Garden for just 100 people. Saloon owners, by contrast, stayed busy.

The Brooklyn Bridge closed to foot traffic by early morning. Ferries soon followed. Thousands gathered along the Hudson River searching for any way home. Ice clogged the river. Some people tried to cross on foot. When the ice broke, many drifted away on floes. Tugboats rescued them one by one as crowds on shore cheered.

Only sleighs moved with any reliability. Cutters and sledges raced along Broadway, throwing snow into the air above rails designed to eliminate sleigh travel. One meat distributor even built a custom sleigh to haul 250 barrels of meat to a waiting steamer.

Disaster Reaches Nyack

Nyack did not escape the chaos. By noon on Monday, blowing snow forced businesses to close and sent schoolchildren home early from Liberty Street School. Drifts reached heights of five to twenty-five feet. Trains on the Northern Line stopped. Telegraph service failed and did not resume until Tuesday night. For nearly two days, Nyack stood cut off from the outside world.

Nyack Cut Off by Snow

In Nyack, the blizzard halted train service on the Northern Line and silenced the telegraph for nearly two days. With roads unplowed and drifts reaching more than twenty feet in places, residents relied on foot travel and sleighs to move through the village. Businesses closed, deliveries stopped, and Nyack functioned in isolation until rail and communication links slowly reopened.

A woman and child walk beside towering drifts that dwarf pedestrians and vehicles alike. The pharmacy visible here disappeared in the early twentieth century. Courtesy of the Nyack Library.

When residents emerged on Tuesday, they found a transformed village. A pyramid of snow blocked the intersection of Main Street and Broadway. Some storefronts stood clear while others disappeared behind drifts. The crossing at Broadway and Burd Street became impassable. At the Reformed Church on Church Street, the janitor spent most of the day digging a tunnel just to reach the building. Storeowners, clerks, and newspaper staff cleared sidewalks by hand. At Main and Franklin Streets, workers carved right-angled passageways through the snow. Horses rarely moved, though a few sleighs ventured out for short rides. Several riders ended those trips buried in drifts.

On the left stands the Doersch grocery, located in front of the Wigwam building. To its right, the Reformed Church and the Commercial Building appear clearly through the snow. Courtesy of the Nyack Library.

Trains Return and Life Resumes

On Wednesday, communication slowly resumed. A train agent walked two miles to the West Shore Railway station in West Nyack. Late Tuesday night, two engines forced their way into Nyack from Sparkill, pushing through drifts as high as the locomotive cabs.

With no mechanical plows available, crews relied on shovels to clear tracks and restore rail service after the storm. Courtesy of the Nyack Library.

By Wednesday night, trains from Jersey City finally brought stranded residents home. Many had slept in stations or rail cars. Others stayed with friends or paid inflated hotel prices. One traveler complained of paying a shocking twenty-five cents for a hard-boiled egg.

A Wedding Delayed and a Storm Remembered

Not every consequence involved commerce or travel. In Nyack, Hannah Hoffman postponed her Wednesday wedding to Herman Levy of Tarrytown when guests could not reach town. The ceremony took place a week later, just before spring. Fifty years on, the couple still remembered the storm that nearly canceled their marriage.

Snow lingered in shaded places well into the spring. Clearing it took weeks, using little more than shovels and horse-drawn plows. The Blizzard of 1888 did not produce the deepest snowfall on record, but it left the deepest mark on memory. For those who lived through it, the storm never faded. It did not bring a snow day. It delivered a snow week.

The intersection with Main Street lies just beyond the two-and-a-half-story building on the right, identifiable by the Fish Market sign. Courtesy of the Nyack Library.

Mike Hays has lived in the Nyacks for 38 years. A former executive at McGraw-Hill Education in New York City, he now serves as Treasurer and past President of the Historical Society of the Nyacks, Trustee of the Edward Hopper House Museum & Study Center, and Historian for the Village of Upper Nyack.

Since 2017, he has written the popular Nyack People & Places column for Nyack News & Views, chronicling the rich history, architecture, and personalities of the lower Hudson Valley. As part of his work with the Historical Society, Mike has researched and developed exhibitions, written interpretive materials, and leads well-attended walking tours that bring Nyack’s layered history to life.

Married to Bernie Richey, he enjoys cycling, history walks, and winters in Florida. You can follow him on Instagram as @UpperNyackMike

Editor’s note: This article is sponsored by Sun River Health and Ellis Sotheby’s International Realty. Sun River Health is a network of 43 Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHCs) providing primary, dental, pediatric, OB-GYN, and behavioral health care to over 245,000 patients annually. Ellis Sotheby’s International Realty is the lower Hudson Valley’s Leader in Luxury. Located in the charming Hudson River village of Nyack, approximately 22 miles from New York City. Our agents are passionate about listing and selling extraordinary properties in the Lower Hudson Valley, including Rockland and Orange Counties, New York.