As the Hudson River waters warm in April, around the time ospreys return and shadbush blooms, millions of shad once headed upstream to spawn. For thousands of years, the Lenape caught and preserved shad as one of their major food sources. European settlers adopted their methods, and a commercial industry thrived into the 19th century. Slowly, and then all at once, the shad migration collapsed. What happened? No one is sure, but river pollution, overfishing, changing water temperatures, power plants, dams in tributaries, and competition from invasive fish like striped bass all contributed to the decline.

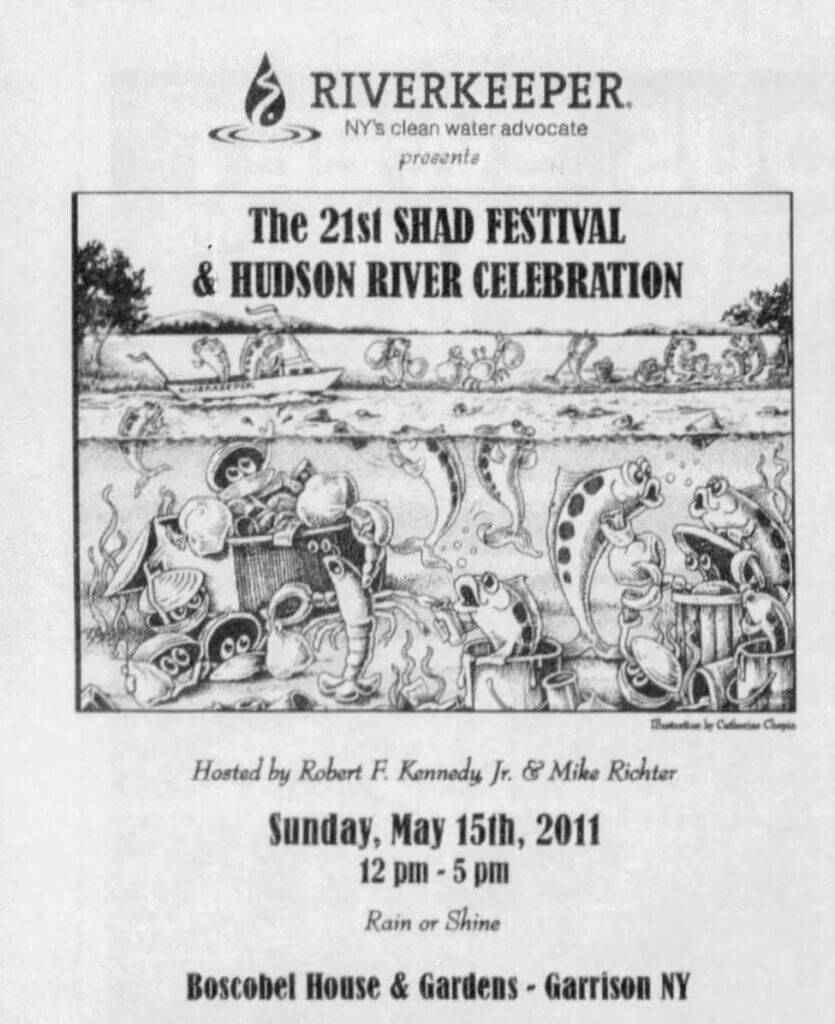

Along with the decline of shad, the tradition of spring shad bakes also faded. Festivals in Sparkill, Garrison, and Nyack, which celebrated shad into the late 20th and early 21st centuries, disappeared by 2011. Today, shad fishing is restricted to catch-and-release only.

Arrival of Shad

Shad return to the freshwater where they were born to spawn. The Hudson River estuary, along with other large rivers like the Delaware, served as major entryways to upstream freshwater streams. The timing of migration remains somewhat of a mystery, but it likely relates to water temperature, as shad do not tolerate cold water. Indigenous people identified the shad migration by the blooming of moss pinks (creeping phlox), marking a period they called the Pink Moon, also known by other Native Americans as the Fish Moon.

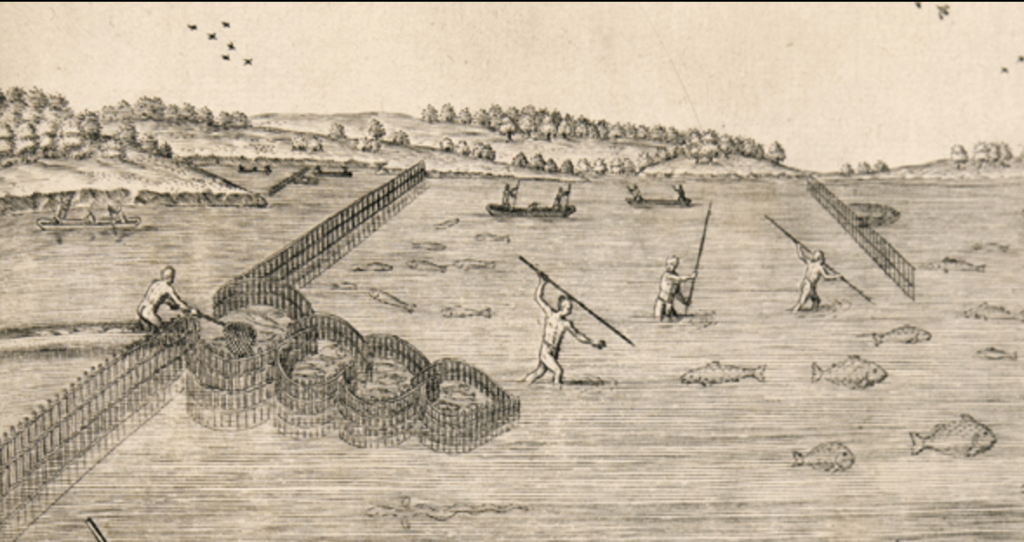

The Pink Moon signaled the time to leave inland winter camps and move to the Hudson River for fishing. V-shaped weirs and nets made from plant fibers trapped the plentiful shad as they swam upstream. People ate shad fresh, dried, or smoked. Shad skeletons, along with oyster shells, have been identified in middens along the river. Dried and smoked fish provided food for months after the spring migration.

American Shad

Shad are known as the fish that fed the founding fathers and their families. Even George Washington managed a fishing enterprise, using enslaved people and laborers to net fish. In 1771, they caught 7,761 shad.

The silvery ocean fish weigh between three and eight pounds. Their flesh has a delicate, sweet flavor and is extremely high in Omega-3 fatty acids. However, shad contain more bones than the human body—about 1,000 in total. Even fillets cut from the side of the fish contain numerous bones. Expert shad deboners are rare. Some recommend baking shad in vinegar to dissolve the bones.

Shad roe, the eggs of the spawning female, is a culinary delicacy similar to sweetbreads. People often sauté it with bacon or butter and lightly season it. Cole Porter’s song Let’s Do It immortalized shad roe in the line, “Why ask if shad do it? Waiter, bring me shad roe.”

While people can catch shad with a line, nets and seines were the traditional method. Fishermen drove posts into shallow waters near shore. As the tide rose, fish would enter the nets and become trapped as the tide receded. Fishermen typically harvested shad twice a day. Commercial boats used purse seines.

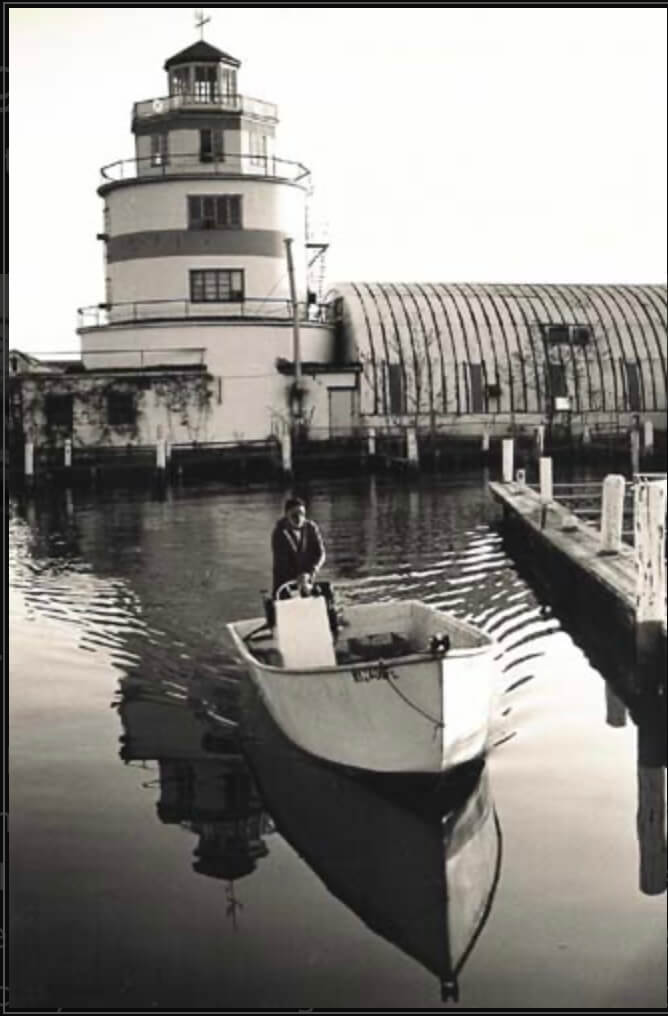

Shad Fishing in Nyack

Shad nets were set in the shallow waters off South Nyack, near where the Tappan Zee Bridge now spans the river. The arrival of shad was noted each year in the local newspaper, though the timing varied widely. The season lasted until May, around the time lilacs bloomed. Even as late as World War II, fishermen took millions of pounds of shad from the Hudson. The fish were baked, pickled, and smoked, while the roe was sautéed.

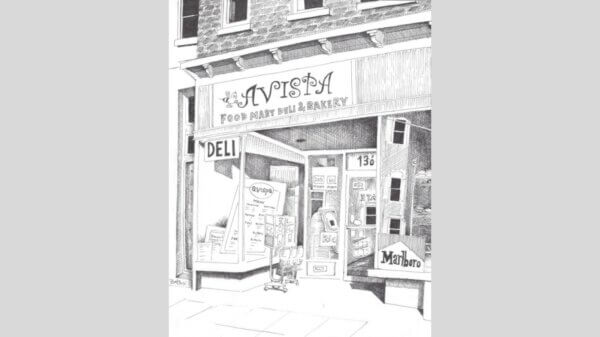

By the late 19th century, shad populations had already begun declining due to dams built on freshwater streams. In response, New York State began raising millions of shad fingerlings to repopulate the Hudson River in 1890, a practice that continued for years. In Nyack, people could buy fresh and live shad at the North River Shad Depot on Main Street. Salted shad was also available, and some customers received deliveries by wagon.

Shad populations fluctuated, with the last major migration occurring in the 1980s. In 1975, cancer-causing PCBs were discovered in the Hudson River. While PCBs affected resident fish more than migratory species like shad, New York State banned the harvesting of resident striped bass, causing their population to explode. Larger and more aggressive than shad, striped bass preyed on shad and their fingerlings, hastening their decline. Invasive zebra mussels eat the plankton upon which shad feed. At the same time, power plants sucked juvenile shad through intake screens, further reducing their numbers.

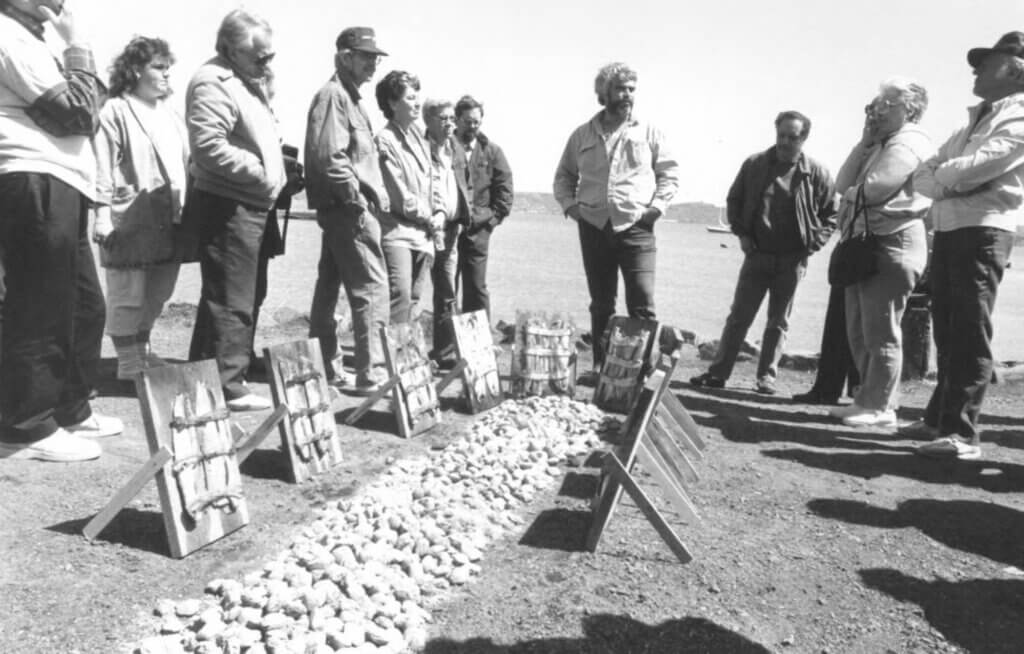

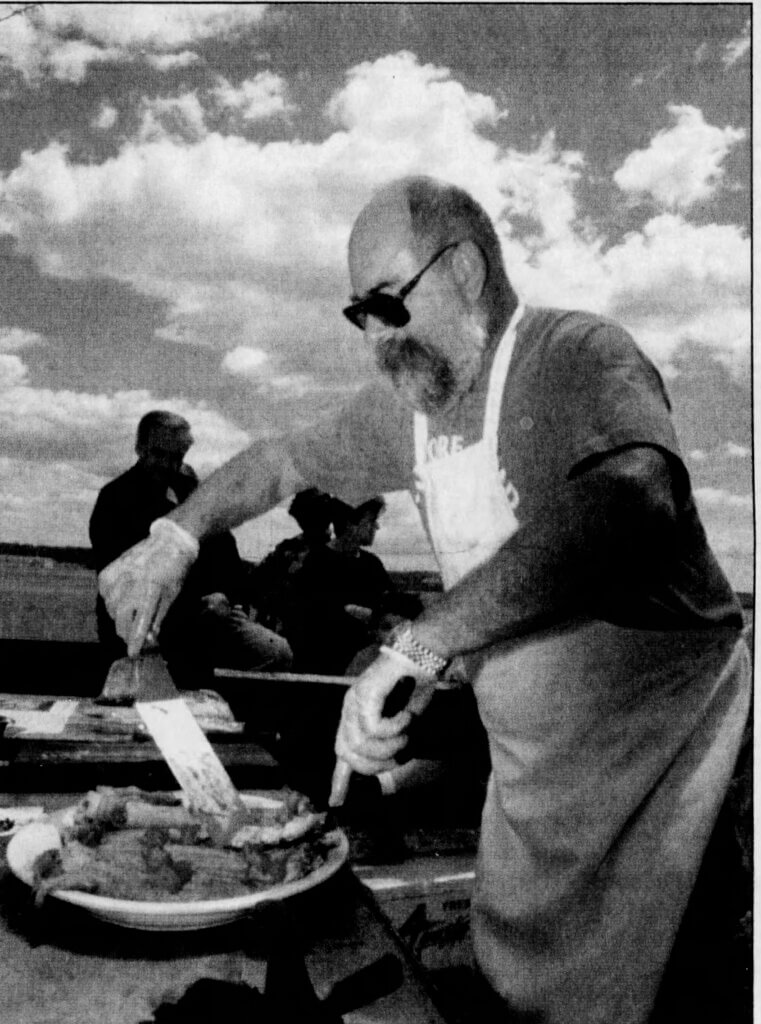

Shad Festivals

Beginning in the 1980s, Nyack hosted shad festivals at Memorial Park or the nearby docks. Fishermen showcased their craft, and visitors tasted plank-smoked shad cooked over wood fires. Folk singers—including, at times, Pete Seeger—and the Riverkeeper organization participated in the events. However, as shad disappeared, so did the festivals.

In 2010, with the population in steep decline, New York State banned shad fishing. The fish, the fishermen, and the festivals all faded away. The last local commercial shad fisherman, Bob Gabrielson—often profiled in the media and featured in the film The Last Rivermen—died in 2009.

The Future of Shad Migrations

Some shad still return to spawn. Whether they will ever return in the numbers they once did will be a slow process depending on habitat restoration. Until then, the sweet taste of shad and shad roe will remain a mystery to future generations.

Mike Hays lived in the Nyacks for 38-years. He worked for McGraw-Hill Education in New York City for many years. Hays serves as President of the Historical Society of the Nyacks, Vice-President of the Edward Hopper House Museum & Study Center, and Upper Nyack Historian. . Married to Bernie Richey, he enjoys cycling and winters in Florida. You can follow him on Instagram as UpperNyackMike.

Editor’s note: This article is sponsored by Sun River Health and Ellis Sotheby’s International Realty. Sun River Health is a network of 43 Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHCs) providing primary, dental, pediatric, OB-GYN, and behavioral health care to over 245,000 patients annually. Ellis Sotheby’s International Realty is the lower Hudson Valley’s Leader in Luxury. Located in the charming Hudson River village of Nyack, approximately 22 miles from New York City. Our agents are passionate about listing and selling extraordinary properties in the Lower Hudson Valley, including Rockland and Orange Counties, New York.