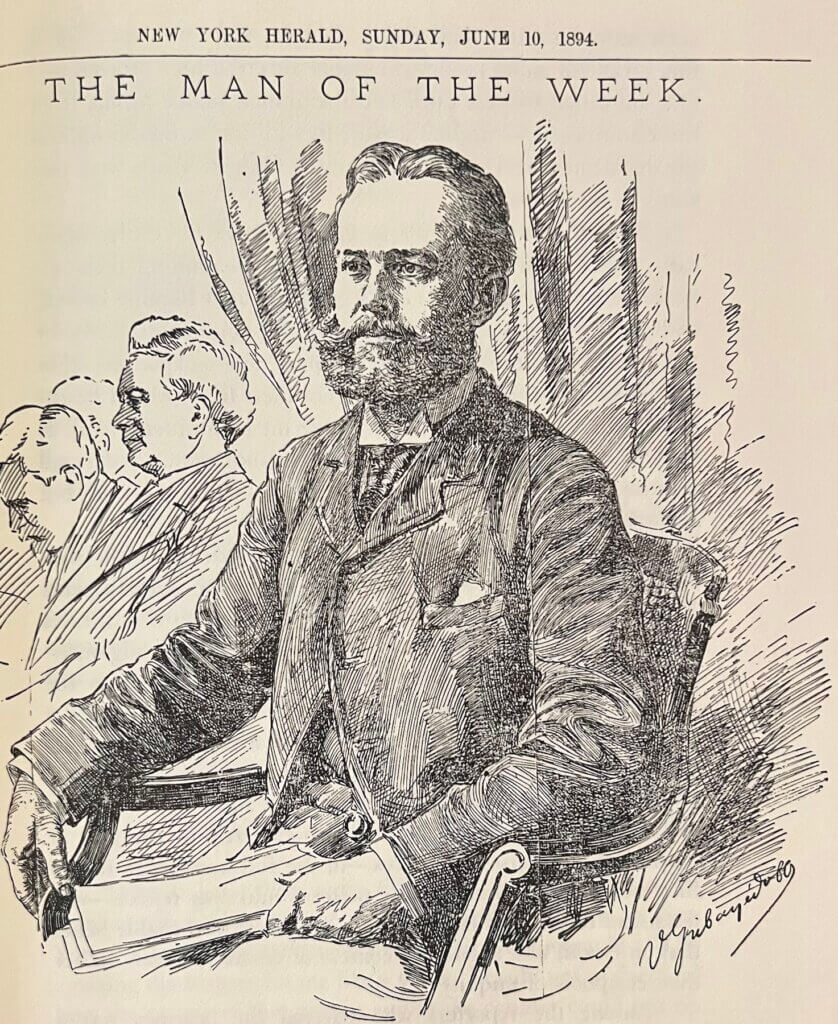

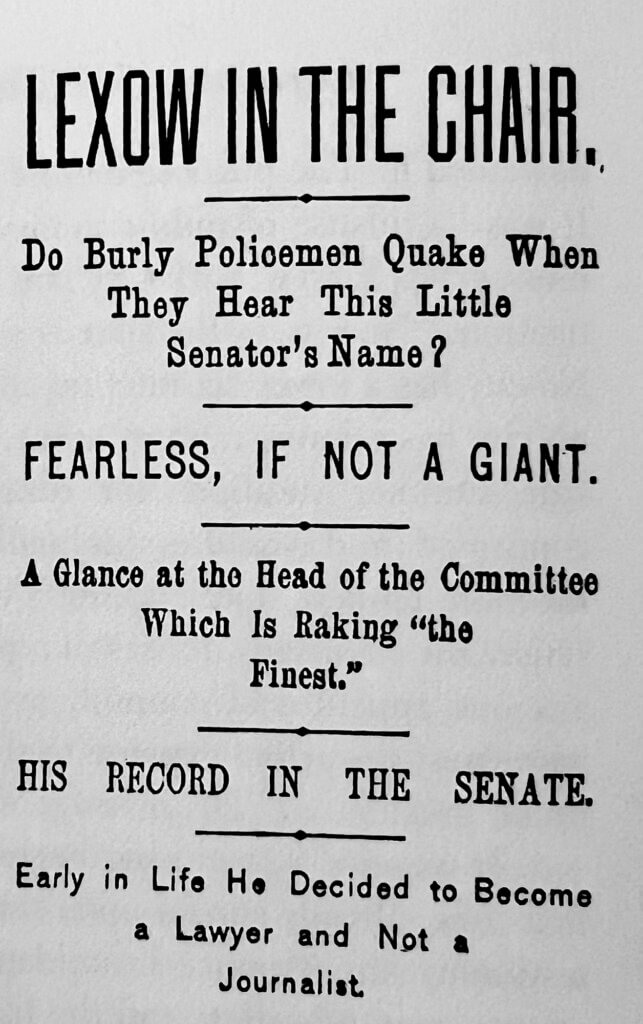

Standing at a mere 5’2”, Clarence Lexow earned the moniker of the “little Nyack Senator with amusing whiskers and a grand top hat.” Nevertheless, from 1894 onward, Lexow rose to national prominence as the head of a committee investigating police corruption within New York City’s Tammany Hall. This committee, later known as the Lexow Committee, played a pivotal role in forcing Boss Croker, the leader of Tammany Hall, to resign and escape to Europe.

This significant moment could be seen as the inception of the progressive movement in the United States. Beyond this, Lexow initiated crucial legislation, prospered as a South Nyack family man, accumulated wealth, and played vital roles in several Nyack businesses and utilities. Here unfolds the tale of Nyack’s Little Giant.

Early Life

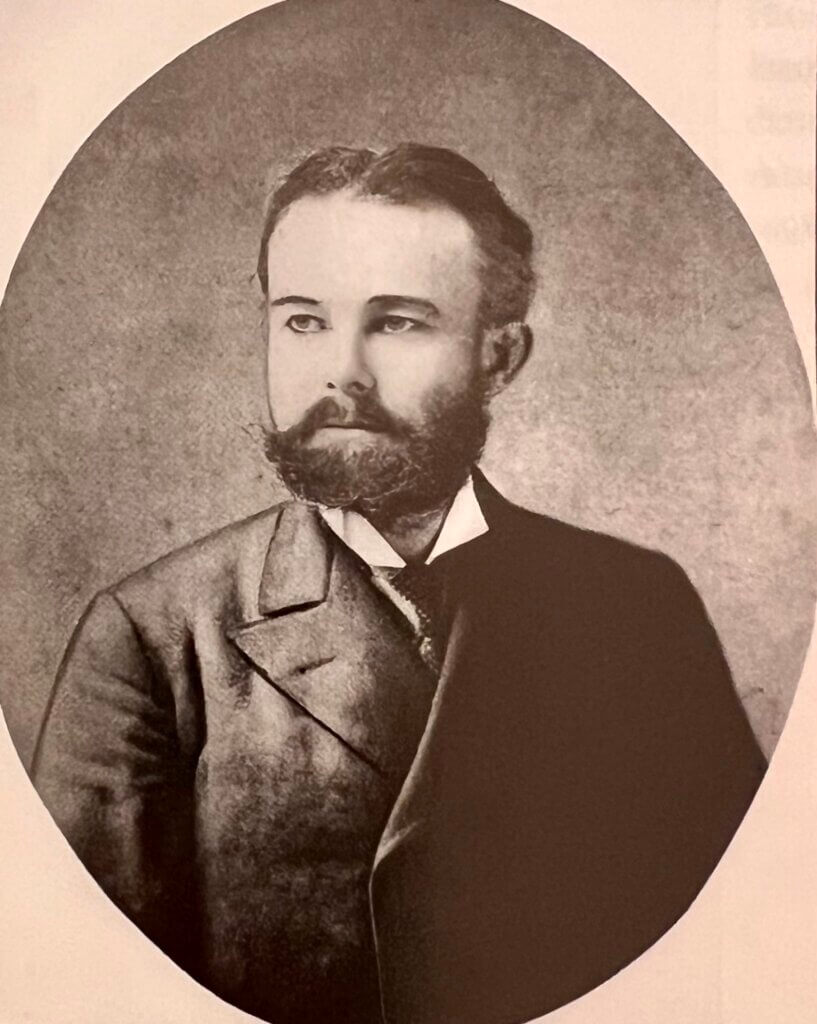

Born in 1852, Clarence was the second son of Rudolph Lexow, a German businessman intellectual who had to emigrate to America due to his involvement on the opposing side of the German Rebellion of 1848. Rudolph’s serendipitous meeting with Caroline King, Clarence’s mother, occurred in Hull, England, during his journey to America. The two eloped, leaving their former betrotheds behind.

Clarence’s birthplace was Brooklyn, in 1852. Lacking a middle name, Clarence sparked Republican comments when he ventured into politics, becoming a man “who doesn’t split his name in two.” After moving to Nanuet and a large farm known as Rock Manor, he began attending a one-room school. Nonetheless, his father, a well-educated individual fluent in eleven languages, aspired for a more elevated path for his son. Thus, Clarence pursued studies at the German American Institute in Brooklyn, concluding his academic journey at the University of Bonn and Leipzig, focusing on philosophy and literature.

Ironically, at the University of Bonn, one of Clarence’s peers was the offspring of Chancellor Bismarck – the very figure whom Rudolph’s articles during the 1848 rebellion had incensed.

During his schooling, Clarence adhered to liberal and socialist doctrines. His participation in protests led to three arrests. Amidst this, he composed romantic poetry, mirroring his father’s penchant for progressive politics and intellectual pursuits. Rudolph anticipated Clarence’s involvement in the family publishing business; however, the decision to enroll at Columbia Law School upon his return to America left Rudolph astounded. Graduating at the age of 22 in 1874, Clarence embarked on a different path.

Marriage

While practicing law in New York City, Clarence met Katharine Morton Ferris, a member of a prominent New York City family, during a Long Island vacation. Her father worked as a stockbroker, and their residence was on 42nd street near the now-iconic Bryant Park and New York City Library. The couple married in 1881, relocating to Nyack the following year, just as their first child, Caroline, was born – a daughter who would later achieve fame as a national suffragette.

Interestingly, Clarence had an unusual fondness for shooting and frequently embarked on hunting trips during his adult years. He also enjoyed bowling, pool, and even participated in a charitable living whist game at the Nyack Kirmess. His travels were extensive; he even journeyed to Honduras with his brother Allan, who later became president of the Cab and Maxi Company, one of the largest cab companies in New York City. Clarence also owned one of the first automobiles in Nyack, a 1903 single-seat, one-cylinder, bright red Cadillac. His son, Morton, frequently drove it around Rockland County.

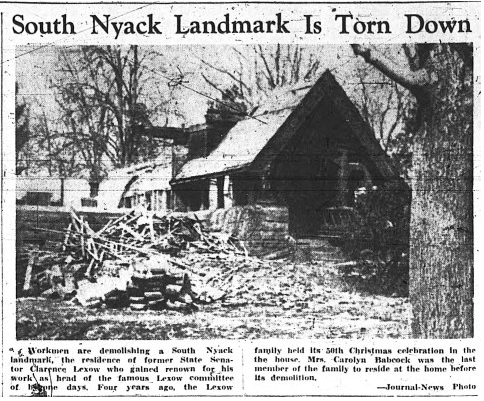

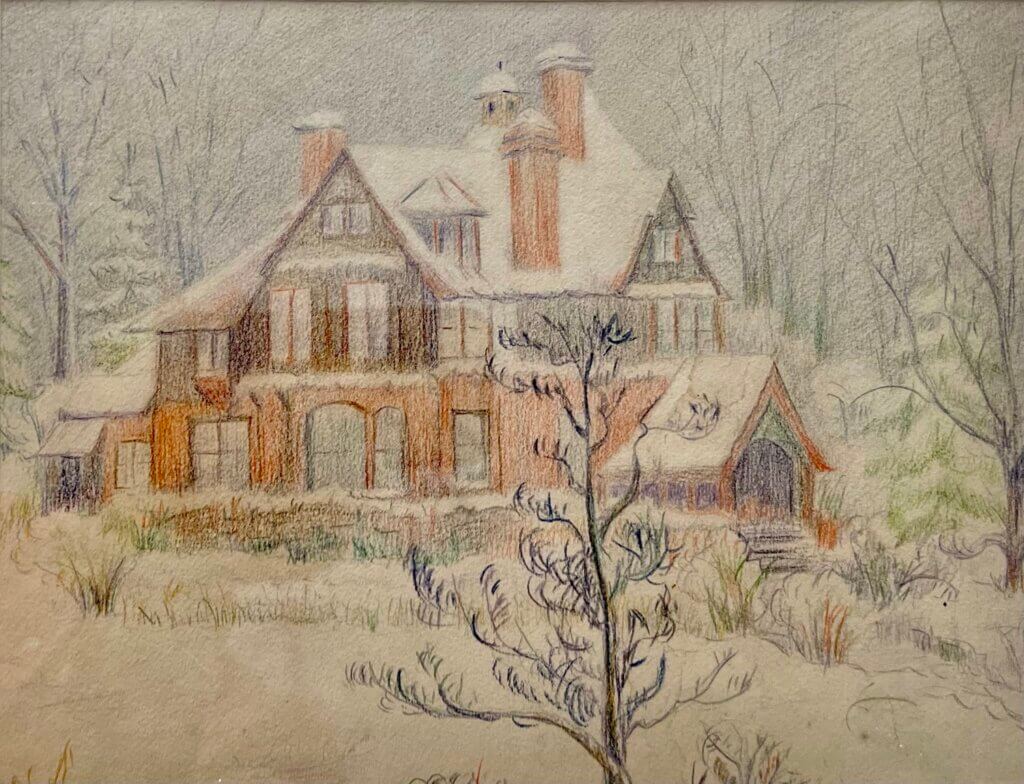

Lexow Home on Piermont Avenue

In 1884, the family settled into their newly built residence, crafted by DeBaun contractors at 298 Piermont Avenue facing the corner of Smith and Piermont Avenues. The lot stretched through the entire block with Cornelison Avenue on the north and Broadway on the west.

Although described as a “cottage” by the newspaper, the house rivaled Clarence’s own stature. Designed in a modified Queen Anne style, it boasted a plethora of architectural features. The stone-clad first floor, shingled second floor with half-timbers, and third floor featuring turrets with distinctive window designs exhibited an array of architectural elements. The wraparound porch with a gabled entrance, alongside prominent chimneys in front and back, further marked the distinctive residence. The house, much like its owner, became a focal point for political activities, not only for traditional Republicans but also suffragette gatherings.

The house was demolished in 1940, and the entire area much changed after construction of the New York State Thruway.

Clarence in Nyack

Following his marriage, Clarence pursued law in New York City while actively participating in the Nyack community. His trajectory had diverged from his socialist European phase and the days when he penned romantic verses to Katherine, one of which appeared in the Rockland County Journal. His progressive politics aligned with wealth accumulation, and his influence grew.

In 1887, he organized the Nyack Electric Light and Power Company, celebrating Nyack’s electrification at the Tappan Zee House, an establishment he would later own. The Nyack Building Cooperative Savings and Loan emerged under his leadership in 1888. His roles expanded as he became the president of the village of South Nyack and the Nyack Boat Club. Active in the Nyack Rowing Association, he also achieved the highest annual bowling score, a feat achieved in the club’s Spear Street bowling alley. His involvement extended to the founding of Nyack Hospital. Reflecting his father’s influence, Clarence acquired the Nyack Evening Star in 1903, a local newspaper, perhaps to engage his political adversaries through print media.

New York State Senator

Clarence’s interest in local politics flourished in his thirties. In 1886, he assumed leadership of the Rockland County Republican Party. Despite an unsuccessful bid for the New York State Senate in 1890 and a failed attempt to become the Republican candidate for Rockland County Judge, Clarence persevered. In 1893, he triumphed, securing election for District 16 of the New York Senate, covering Rockland, Orange, and Duchess counties, with a decisive 4,000-vote lead over Tammany Hall’s Democrat Nelson.

The Lexow Commission

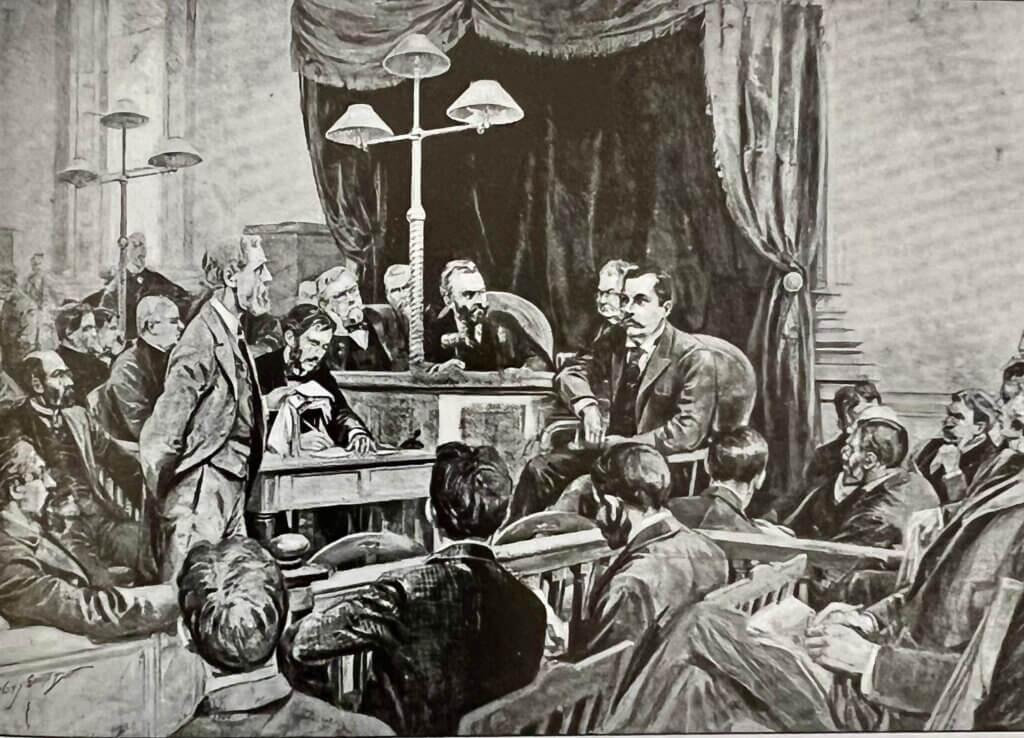

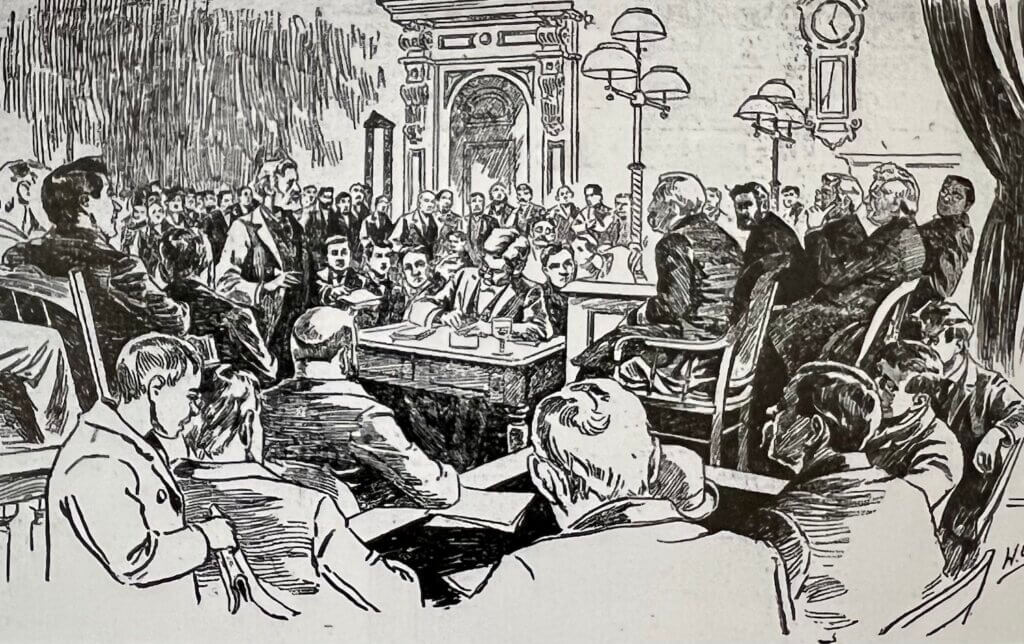

Upon entering the Senate, Clarence promptly introduced legislation to probe the New York Police Department, subsequently heading that Committee. How he attained this prestigious role as a newcomer remains unclear. Perhaps his leadership acumen or absence of apparent political connections played a part. Recognized for his meticulous approach and reputation for integrity and efficiency, his strong ties within the city’s German community, fostered by his father, likely contributed. The Lexow Committee, renowned as the first legislative body to conduct public investigations endowed with subpoena power, soon emerged, promptly referred to as the Lexow Committee

Throughout the year, the committee amassed testimonies from 678 witnesses during 74 sessions. A staggering 10,000 pages of transcripts documented the testimony, and their conclusive report spanned six extensive volumes, totaling nearly 6,000 pages. Captains, commissioners, and inspectors were summoned to address bribes paid by the public and individuals to secure positions as police officers and officials. For instance, becoming a sergeant entailed a $2,500 payment, while captain rank bribes could amount to over $10,000. These appointments yielded Tammany Hall a staggering $7 million annually. Furthermore, collusion among police officers to cast fraudulent votes emerged, alongside evidence of payments, like $30,000 yearly for disorderly house protection, and $300 monthly for pool rooms. Public uproar followed, magnifying the commission’s and Lexow’s nationwide prominence.

Lexow Commission Outcomes

The Lexow Commission’s actions compelled Boss Croker’s resignation and flight to Europe, consequentially leading to Tammany Hall’s electoral defeat and a Republican mayor’s ascendancy in New York City. Theodore Roosevelt’s appointment as police chief, prompted by the commission’s efforts, catalyzed the reform movement that eventually paved the way for his presidency. While numerous committee proposals remained unrealized, the city regrettably reverted to past practices once the headlines waned.

Throughout his tenure as chairman, Lexow weathered invectives from Tammany Hall and opposing media. He was dubbed the “little whipper snapper from Nyack,” the “Grand Inquisitor,” and “the tool of the hayseeds from upstate.” The Evening Post even cast doubt on the generation of thoughts in Lexow’s mind.

Instrumental in Forming the Greater City of New York

Had Lexow’s accomplishments ended with his inaugural year of national prominence and Tammany Hall’s curbing, his legacy would still be substantial. Nonetheless, spanning his initial and reconfigured second term in a different district, Lexow instigated additional consequential legislation. In 1896, he played a pivotal role in uniting three cities and 40 villages, culminating in the establishment of the Greater City of New York.

The same year witnessed the introduction of new antitrust laws, including measures against American Telephone & Telegraph. His initiatives extended to primary voting reform legislation, which successfully passed.

Champion of Local Interests

Lexow’s interests extended beyond the realm of city and state affairs. He championed the bill that led to the creation of the Palisades Interstate Park Commission, orchestrated the acquisition of Stony Point Battlefield for preservation as a park, and promoted the safeguarding of the site where Major Andre met his fate as a spy in Tappan during the Revolutionary War.

Returning to Private Practice

For a two-term senator, this legislative record was remarkable. In 1898, he received an offer to become the floor leader of the Republican Party in the senate and even garnered potential gubernatorial candidacy mentions. Yet, for reasons undisclosed, Lexow chose to forgo reelection, opting to return to private practice.

His tenure at the helm of the Lexow, Mackellar & Wells law firm in New York City spanned his retirement from the senate until his demise. During this period, he undertook significant cases, including the defense of the American Sugar Refining Corporation in a fraud case.

Simultaneously, he held directorships in three companies: Aetna Indemnity, Title and Guaranty Company of Rochester, and the South Shore Traction Company (street cars), solidifying his status as a wealthy figure.

Lexow’s Enduring Impact

Notably, he did not rally behind the suffrage movement, leading to a rift with his daughter Caroline, who left home due to his lack of support. Evidently, his progressive ideals did not extend to women. At the age of 58, Clarence Lexow succumbed to severe pneumonia, leaving behind a legacy that reached beyond his years. His final resting place lay beside his father in Oak Hill Cemetery, an unassuming conclusion to an extraordinary life.

Although largely obscured from Nyack’s modern memory, Clarence Lexow remains a towering figure in the town’s history. Curious minds might ponder the origin of Lexow Avenue in Upper Nyack, an homage to the influential individual behind the appellation. His indelible mark not only on Nyack but also on the state and city of New York remains undeniable. In the Gilded Age, Clarence had an indomitable presence in virtually every civic and social facet of Nyack. His legacy persists as Nyack’s Little Giant.

Michael Hays is a 35-year resident of the Nyacks. Hays grew up the son of a professor and nurse in Champaign, Illinois. He has retired from a long career in educational publishing with Prentice-Hall and McGraw-Hill. Hays is an avid cyclist, amateur historian and photographer, gardener, and dog walker. He has enjoyed more years than he cares to count with his beautiful companion, Bernie Richey. You can follow him on Instagram as UpperNyackMike