It’s been dry and hot this summer, but it’s been a “sweet” heat. Thanks to beekeepers Dana Harkrider and Suzie Quarrell, villagers have been able to buy honey made in Nyack. Harkrider notes that while the bees struggle to find nectar and pollen right now due to the drought, they have nonetheless made more honey than usual this year. Is there something bees know about saving for the future that we don’t? Perhaps. At least right now our village is a little sweeter because of these two enterprising beekeepers who live but a half-mile apart as the bee flies from each other.

Before we hear from our beekeepers, here are some things you should know about bees.

Sisterhood of Bees

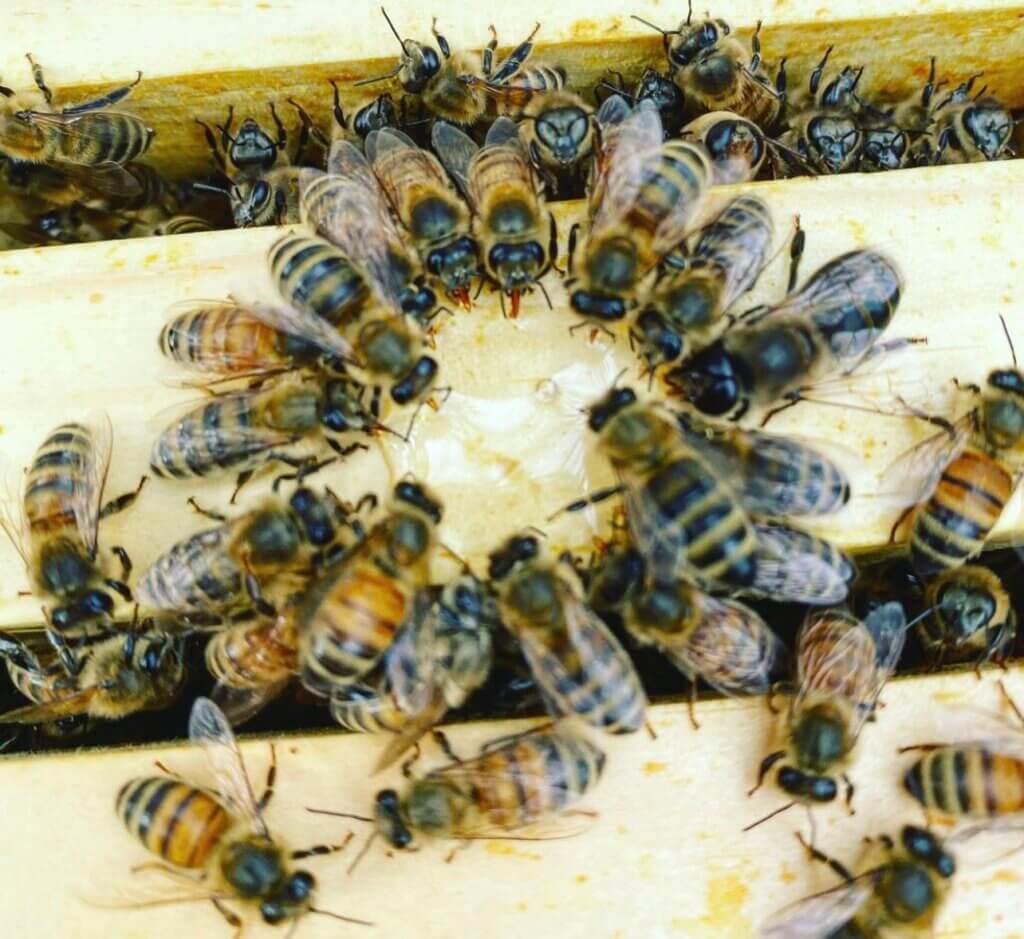

The honeybees here in the US, known scientifically as apis mellifera, are strands of bees originally from Europe. They are different than wild bees. There are tens of thousands of honeybees in a hive but only about 10% to 20% are males. Female bees, appropriately known as worker bees, do all the work in the hive. Each bee has a specific task. They start first as nurse bees, taking care of the baby bees, then slowly graduate as they age to queen consorts, construction workers, cleaners, undertakers, and guards. The last job they take on in their lives is as foragers.

Male bees, known as drones, have only a single function, which is to mate with new queens. Since there are no new queens being born in winter, there is no need for drones in the hive during winter. Their sister bees therefore slowly starve their brothers during the autumn and kick them out of the hive.

Bees communicate through a complex set of dances, as well as through touch and pheromones. They beat their wings inside the hive to dry out nectar to turn it into honey. Bees cluster together and shiver their wing muscles to warm the hive during the winter. They keep themselves quite toasty throughout the winter—the center of their cluster can reach 92 degrees, the outer fringes 70 degrees.

Swarming versus Absconding

Half of a colony of bees “swarm” or leave the hive with the old queen to establish a new colony. Swarming is a natural biological form of colony reproduction and usually happens in spring when food is abundant and honeybee populations are rising. Several new baby queens (one of which will kill the other queens and assume the single queen role) are left behind in the original colony so that those bees can continue to thrive. Before swarming, scout bees will search for potential locations for their new home. Their dance upon returning to the hive communicates the location they found. More scout bees will go check out the location, ultimately “voting” on which location they like best, and eventually the swarm moves. It looks like chaos, yet the swarm can decide using “swarm intelligence” about where to set up a new colony.

Occasionally bees will leave the hive entirely, a process called absconding. While swarming is a form of reproduction, absconding usually occurs when something is wrong, for instance, the colony is overcome by pests, parasites, disease, predators, or a lack of forage.

There is no “i” in Bees

A honeybee colony is a great example of a ‘superorganism,’ a group of individual organisms that all function together as if they were one organism. In everything they do, honeybees are always singularly focused on the survival of their colony, not on their needs as individuals.

Harkrider Hives

Dana Harkrider (@HarkriderHoney on Instagram) became interested in keeping bees about 15 years ago in 2006 when she read an article about colony collapse disorder, a strange phenomenon that was killing honeybees at the time. She thought, if we don’t do something about this, it will be a big problem for bees and humans alike! For her, one practical solution was to become a backyard beekeeper. After she and her husband moved to Nyack in 2010, Harkrider took a year-long class at the Stone Barns Center for Food and Agriculture in Westchester, spending time in the apiary mirroring what she was doing with her own bees. Later, she completed advanced training in the Cornell University Masters Beekeeping Program earning a master beekeeper degree.

“From the first time I went into an apiary and worked with bees flying around me, I was hooked. These little beings are magical, the way they work together and communicate with each other.”

Dana Harkrider

Location, Location, Location

Harkrider started beekeeping with her friend Yvonna Kopacz-Wright on Wright’s six-acre farm in Palisades, NY. Like the way bees share tasks to support their family, the two beekeepers work together to care for their bees. Under the name Lomar Farms, Wright makes and sells beautiful hand-poured beeswax candles. Soon after setting up the hives in Palisades, Harkrider added a single hive behind her house at the corner of N. Franklin St. and 5th Ave. and started planting her whole property with native flowering species. While bees will extract nectar from their immediate surroundings, they will travel up to three miles in all directions to find the best sources of pollen and nectar. But Harkrider advises that keeping bees means planting flowers. “I tell my clients that even though your property is not your bees’ only source of forage, you should plant your property as if it is.”

Master Beekeeper

In addition to raising her own bees, Harkrider helps clients set up apiaries on their own properties. Her clients are individuals or families with the space and desire to have honeybees but simply need help caring for them. Clients can be as involved with their bees as they prefer… some want assistance for the first few years until they learn to manage their bees themselves whereas others leave all the beekeeping to Harkrider. In total, she handles 30 hives throughout Nyack, Upper Nyack, and Palisades.

Additionally, Harkrider tends the bees at Closter Farm and Livestock, an organic farming venture in Closter, NJ. She also teaches two classes there, Beekeeping 101, an intro to beekeeping class for adults ages 12 and up, and Beekeeping for Kids, a one-hour class for children ages 6-12 about the amazing lives of bees.

Suzie Quarrell, Beekeeper

Suzie Quarrell (@thehumblebeeshoney on IG), an adjunct lecturer in literature, has always been interested in honeybees. Several years ago, she saw Harkrider’s “Honey-for-sale” sign at her house on Franklin and 5th. While buying honey, Harkrider told Quarrell about her work with bees. When Quarrell heard, “I would be happy to mentor you,” she was hooked. She received her first package of bees in 2019. Now she has four hives.

“I fell madly in love with bees, the hive mind, the way the bees interact with each other. It’s so fascinating.”

Suzie Quarrell

Quarrell said she read a lot of books on bees, watched many YouTube videos about beekeeping, and joined local beekeeping Facebook groups. There are many different opinions about beekeeping says Quarrell, but Harkrider is the best teacher, “She has a wonderful way with bees, very Zen, calm, and slow. If you are calm around bees, they are calm especially during the inspection process.”

There is a steep learning curve to beekeeping, she says. All bees look the same at first. It took her awhile to identify the queen and the eggs with her bee equipment on. In addition to raising bees, she is a participant in the Pollinator Pathway initiative and has added many native species to her existing collection of native trees and flowers.

Her first big challenge occurred when she accidentally banged on one of the hives without her bee suit on. A thousand bees chased her around, stinging her several times. Quarrell says that “the only time I get stung is when I don’t have my gloves on.”

A Taste of Honey

Harkrider likens local honey to single vineyard wine. Winemakers call this “terroir” or the special character that a given place imparts to the fruit, a combination of climate, topography, soil, and weather. The taste of honey has a similar sense of “terrior”. The taste varies by season and types of flowers. Some beekeepers will produce a specific flavor by taking hives to a monocultural area, say a field of clover, to impart a specific flavor. Wildflower honey has more layers of flavor.

Quarrell note how much the taste varies by season. She finds spring honey to be lemony, fall to be richer and heavier. Quarrell currently focuses on raw single origin honey and makes a hot and spicy honey that is very popular. This winter she plans to experiment with smoked honey.

Are Bees Going Extinct?

A common misconception in the media is that honeybees are going extinct. Honeybees are indeed suffering major challenges from parasites like the varroa mite, pesticides, climate change, and loss of natural habitat to development, but honeybee populations are managed by beekeepers. Honeybees are essentially livestock. If beekeepers lose honeybee colonies over winter or because of disease or parasites, beekeepers can regrow their apiary populations. Because honeybee colonies are managed, they are in no danger of going extinct. It’s native bees—the wild species of bees that are also suffering from our degraded natural environment but who have no keepers caring for their welfare—that are facing extinction.

Nyack Pollinator Pathway Project

Just when you think that the extinction of native bees is a fait accompli, a local solution has appeared. Harkrider cofounded Nyack Pollinator Pathway with Lorien Barlow in 2019 with the goal of providing habitat in urban spaces for pollinators like bees, hummingbirds, and butterflies. With the backing of the Village of Nyack, the Nyack Pollinator Pathway has planted multiple pollinator spaces in underutilized natural areas along Main St., in Memorial Park, by the bus stop at Artopee & Franklin, and outside the gate of the Nyack Community Garden.

More plantings are planned and the Pathway is growing… to get involved, visit here to learn how to start your own pollinator garden, join the Pathway’s mailing list, or to make a tax-deductible donation (any amount is welcome!).

You Gotta Be Quick

Both beekeepers offer their honey for sale. It doesn’t take much more than the signs in their yards and word of mouth to sell their honey. Quarrell sells raw, single origin honey and is already sold out for the year. Harkrider currently has three different honeys made from her hives at Lomar Farms, her own hive at her house on the corner of N. Franklin and Fifth Ave, and from hives she keeps on Lexow Ave, but she predicts she’ll easily run out of honey by the fall. So, get in line. You can’t get more local or more natural than this, making Nyack honey the best you will ever taste.

Michael Hays is a 35-year resident of the Nyacks. Hays grew up the son of a professor and nurse in Champaign, Illinois. He has recently retired from a long career in educational publishing with Prentice-Hall and McGraw-Hill. Hays is an avid cyclist, amateur historian and photographer, gardener, and dog walker. He has enjoyed more years than he cares to count with his beautiful companion, Bernie Richey. You can follow him on Instagram as UpperNyackMike.