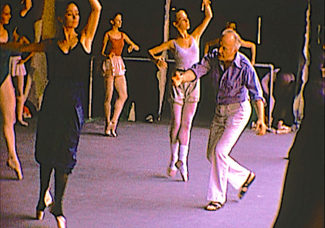

“The classroom was where he went to see how far he could make his dancers go,” says a former student in the opening of In Balachine’s Classroom. She is among a chorus of voices contextualizing the perspectives and choreography of George Balanchine at a critical juncture in American ballet. The rise of Balanchine’s New York City Ballet is chonicled in a new documentary streaming with Rivertown Film Society online starting February 4th.

From here, the film—loaded with sweeping takes of ballerinas and never before seen footage of Balanchine—creates a collective dream of the vocabulary developed in Balanchine’s daily work with dancers and what he believed the body to be capable of, approaches to movement that others had yet to imagine. For him, success was when a dancer broke through, when they were in the moment rather than simply performing rehearsed gestures (but it took lots of rehearsal to get there).

From here, the film—loaded with sweeping takes of ballerinas and never before seen footage of Balanchine—creates a collective dream of the vocabulary developed in Balanchine’s daily work with dancers and what he believed the body to be capable of, approaches to movement that others had yet to imagine. For him, success was when a dancer broke through, when they were in the moment rather than simply performing rehearsed gestures (but it took lots of rehearsal to get there).

Many of the female dancers reflect on the idea of beauty and the time they took into molding to what that they believed would get them the attention and approval of their beloved instructor. “We wanted so badly to be exactly what he wanted us to be,” says performer Lisa de Ribere. Balanchine’s dedication to teaching also raises the question, one that director Connie Hochman herself had in making the film, why was such an incredibly talented choreographer in a classroom? Why did he teach? What was in it for him?

This is something a lot of artists who teach asks themselves, and other than the easy answer of teaching paying rent, which for many it does, the classroom is also an experimental, even transgressive space, one where the risk of an idea can take shape for both student and instructor without an audience. This seemed to be the philosophy of Balanchine, whose former students describe his classroom as a space where they were told impossibilities like, “ballerinas do not belong on this earth.” He warned his dancers against marriage, saying he didn’t want dancers who wanted to dance, but needed to. Those who gave their life. Teaching was inseparable from Balanchine’s art.

Mondays in his classroom were packed, but by the end of the week the room would be down to fifteen. His focus was on breaking through their individual thresholds, of helping them uncover their own genius. This might feel like a familiar trope, reminiscent of the demonic bandleader in Whiplash or have tinges of countless abusers in the art world, but the students of Balanchine remember their time with him as reaching a spiritual dimension. Now, his former students are teachers themselves and question their impact, if everything they do to pass down his lessons only further waters them down.

Rivertown Film Society’s virtual panel discussion on February 16th at 6 PM EST welcomes former New York City Ballet dancers Antonia Franceschi, Jean Pierre Frohlich and Christine Redpath and former New York City Ballet musician Cameron Grant to discuss George Balanchine’s vision, training method, his dances, and why we still talk about his life today. Robert Gottlieb, author of George Balanchine: The Ballet Maker, shared that “Balanchine knew and assimilated everything about ballet that preceded him and led the way to everything that would follow. He is, without question, the greatest figure in the history of the art form.”

“The way he moved, it was magical,” reflects Edward in the film, a former student and now an instructor himself. The images accompanying the claim show Balanchine in flight, arms spread like wings, feet bent in difficult angles. “The real life, the real reality…it’s not on earth, it’s not what we can explain with words,” Balanchine says in a recording that plays throughout the film. “Music is the basis, or a floor that we walk on.” He saw dancers in service to the time constructed by a composer, and movements as a way to express that time.

And his life is a lesson in time—and patience. Tried under different names and compositions, it took Balanchine 15 years to found New York City Ballet in 1948 at New York City Center: wooden floors, no mirrors, chairs used instead of ballet bars. They couldn’t draw an audience until their second season. The success led to Balanchine having his own theater at Lincoln Center: the New York State Theater. Here, Balanchine worked on three or four ballets at a time, making use of the resources finally at his disposal until his death.

The moderator of Rivertown Film Society’s discussion, Diana Byer, is the founder, president, and artistic director of New York Theatre Ballet and its training school, New York Theatre Ballet School. She performed as a principal with the company and as a guest artist with ballet companies throughout the U.S. She will be joined by Jean Pierre Frohlich, Repertory Director for the New York City Ballet and former student and Soloist; Christine Redpath, a Ballet Master at the New York City Ballet and former Soloist; Antonia Franceschi, an alumnus of the New York City Ballet; and Cameron Grant, a pianist for the New York City Ballet for 37 years. All of the participants have worked with George Balanchine.

Get your tickets for In Balanchine’s Classroom and register for the discussion at www.rivertownfilm.org.