The Bomb Cyclone That Changed New York

by Mike Hays

Looking north on S. Broadway toward Main Street. In the foreground is the Christie town pump and a block of buildings known as the Post Office Block. The snow in the street is as tall as the people walking on the sidewalk.

A little after midnight on Monday morning, March 12, 1888, heavy rain changed to sleet and then to a heavy, wet snow driven by howling winds. Today, phrases like bomb cyclone, polar vortex, thunder snow, and Siberian express are touted by weathermen in advance of many potential winter storms sending everyone to the store for bread and milk. Back in the day, warnings were less conspicuous. No one predicted a major snowstorm let alone a blizzard on March 12, 1888. From Wall Street financiers to six-year-old Edward Hopper in Nyack, life stopped the day the northeast corridor was buried in snow.

In Nyack, as in Gotham, winds swirled, banged, and roared. It was hard to open doors, shutters were frozen shut, sides of buildings were plastered in wind-driven wet snow. Walking was hazardous especially for women in petticoats. Without fresh milk delivery, households bought some 879 cans of evaporated milk in a village of 4,000.

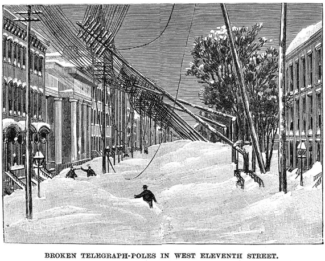

Many sources rate the Blizzard of 1888 as the worst winter storm, in part because it affected such a large percentage of the U.S. population. The experience was so shocking that people never forgot what they were doing that day. The shutdown of surface transportation in Boston and NYC resulted in the building of subways that were more protected from winter storms. Telegraph and electric wires were buried underground in some places. It was also the first large-scale disaster to be photographed. If you think the hoopla about the storm was hyperbole, just look at the photos.

The Great White Hurricane

Headline in the New York Sun.

The storm that barreled up the Atlantic coast on March 12 was unusual. A wet low traveling from the south met an incoming Canadian cold front. The swirling winds resulted in a classic nor’easter. Just as the storm was passing New York, it made a 360-degree loop before heading north. While snow abated, winds did not. Some 200 ships were grounded in a stretch from the Chesapeake Bay to the eastern shores of Canada. Boats as far south as Delaware were sunk even in safe harbors.

Before the storm on March 10, the temperature was in the 50s. Rain turned to snow at 1a on March 12, 1888. By morning, the winds were 50 mph. The temperature was 24 on Monday and fell to 6 on Monday night (still a record for that date.) Winds were still 40 mph on Monday night. Snow stopped at end of day on Monday. Snowfall was tough to measure because it was so uneven. Central Park measured 21”, parts of Brooklyn and Queens measured 36”. The further inland and the further upstate, the snowfall was worse. Saratoga Springs topped out at 56”. Wind was so strong that the ground was bare in some places and in other places huge drifts were piled. A 40-ft drift was measured in Duchess County.

New York City

Some 200 people lost their lives in NYC including the president of the ASPCA, Henry Bergh, who was buried in snow. Roscoe Conkling, America’s leading Republican and a Wall Street financier tried to walk home from his office but was overcome, ended up in a hospital and died a week later. Trains, streetcars, mail delivery, ferries, telegraph, horse cabs, and carriages ground to a halt. Normal deliveries of milk and newspapers stopped. Suddenly, all communication stopped. It was like what would happen today if the Internet suddenly didn’t work.

Some 200 people lost their lives in NYC including the president of the ASPCA, Henry Bergh, who was buried in snow. Roscoe Conkling, America’s leading Republican and a Wall Street financier tried to walk home from his office but was overcome, ended up in a hospital and died a week later. Trains, streetcars, mail delivery, ferries, telegraph, horse cabs, and carriages ground to a halt. Normal deliveries of milk and newspapers stopped. Suddenly, all communication stopped. It was like what would happen today if the Internet suddenly didn’t work.

Hotels were overflowing. Astor Place added 200 cots to accommodate stranded travlers. One woman was given a chair in the lobby and later moved to a bathroom. The Hanover Bank had fifteen employees in a single room. People were stranded on trains. Passenger cars had wood stoves to keep people warm, but as wood ran out, card tables and seats were chopped up for fuel. Stores tried to keep their sidewalks clear, but few customers and clerks reached shops. “L” (elevated) train stations were kept warm by stranded station managers offering some refuge for those trying to walk. Most theaters were closed but Daly’s put on A Midsummer Night’s Dream to an audience of 150 people, although many stand-ins were used for actors who couldn’t make it. The Barnum circus went on as planned at Madison Square Garden but only 100 people attended. By contrast, bars bucked the trend. They were packed.

Winds were fierce on Wall Street.

Pedestrian traffic was stopped over the Brooklyn Bridge at 6a and then trains stopped running. Ferries stopped running. Thousands crowded the banks of the Hudson River looking for some way to get home. Ice jammed the piers and some of the more adventurous tried to cross. Many made it but at some point, the ice split up and many were stranded on ice floes. Six tugboats went to rescue them, five getting stuck themselves. The sixth pushed a floe with the largest number of people to the wharf and then gradually picked up people on the smaller floes. Crowds of stranded travelers on shore cheered.

The only things that moved were sleighs. Cutters, Russian sledges, and sleighs of all sorts sent plumes of snow in the air as they went up and down Broadway above rail tracks laid to eliminate the need for sleighs. Alexander Powell, a meat distributor found a solution to get 250 barrels of meat and poultry to a steamer in the harbor by building an improvised sleigh.

Sidewalks cleared in New York City.

Wall St. closed at noon since few traders were able to get there and communication with other cities was lost. Roscoe Conkling left Wall Street at 6p refusing to pay a cab $50 for a ride. He headed up Broadway to his home. He described the walk, “I had an ugly tramp in the dark — the lights out, from Wall Street up, over drifts so high that my head bumped against the signs, and dug-outs opposite the store doors suddenly letting a wayfarer down a foot or two over snarled telegraph wires and slippery places, with a blizzard in front not easy to stand against, and so cold as to close the eyes with ice, and drifts were not packed enough to bear up, in which one sank to the waist.” He made it to Union Square where he got stuck in a snow drift for 20 minutes his hands and face freezing. He made his way out until he made it to the New York Club at 25th Street and was later hospitalized. He died a week later.

Train Wreck

In Nyack, a lone horseman on Broadway heads past the Doersch grocery toward Main St.

At 7:43 Monday morning, a serious train wreck occurred on the 3rd Street elevated resulting in the death of one engineer. Trains were crowded that morning, and many didn’t stop at crowded train stations. The 76th St. station was at the bottom of a steep grade between 84th and 67th Streets. As the rails were slippery, many conductors just kept going through the 76th St. station to maintain momentum. One train stopped after 7a. It was already a full train, so it pulled through the station so that only the last car platformed. The train remained there for 20 minutes because of traffic ahead. Meanwhile a packed train at 84th St. decided to go full steam ahead to clear the grade after 76th. The engineer and conductor jumped from the train when they saw it would hit the standing train. Miraculously only the engineer of the forward train was killed.

Blizzard in Nyack

The Rockland County Journal was a weekly newspaper. This rather tame headline appeared on March 17, five days after the storm.

By noon, blowing snow made travel difficult. Businesses began to close, and school children were sent home from Liberty Street School early. Some places were blown free of snow by the wind. In other places snow accumulated in drifts ranging from 5 to 25 feet. Trains stopped moving on the Northern Line. Mail that came by rail was not delivered. The telegraph went out on Monday and didn’t come back online until later Tuesday. Nyack was essentially cut off from the outside world.

Tuesday Snow Shoveling

N. Broadway in Nyack looking toward Main Street. The tall brick building in the background still stands and houses Pickwick Books. Villagers seem to be posing for the photo. A carriage with two horses struggles up the street.

Villagers ventured out on Tuesday after the snow stopped. In downtown Nyack a pyramid of snow stood in the intersection of Main and Broadway. News reports stated that along Broadway, some shops were totally clear, but others were covered. The crossing at Broadway and Burd St. was impassable. It took the janitor of the Reformed Church at Church Street most of the day to dig a tunnel into to the church. A snow bank in the front of the post office (then located where Nyack Plaza is now), the Doersch grocery, and Van Houten’s market made it nearly impossible to see the Nyack National Bank across the street.

A similar snowbank some six feet high blocked the businesses on the west side of DePew Place, the three-story brick buildings that today stretch south from Hudson Ave. No fancy snowplows seemed to be at work in Nyack. Storeowners, clerk, and the staff of the Rockland County Journal cleared the sidewalks. At the corner of Main and Franklin, passageways were dug at right angles to navigate the intersection.

Horse travel was impossible for the most part although a few got out their sleighs, mostly put away for the winter, and took a joy ride. Many sleight riders ended up pitched into deep drifts.

Wednesday Train Arrivals

Photo taken in front of the Dutch Reformed Church at Church St.

Communication with the outside world finally started to reopen on Wednesday. A train agent made it to the West Shore Railway station on foot in West Nyack some 2 miles away. Two train engines pushed through deep snow on the Northern Line into Nyack from Sparkill late Tuesday night. Engineers stated they encountered drifts that reached to the top of the engine cabs.

On Wednesday night, trains started arriving from Jersey City bringing home those who had been stranded on Monday. Some slept in the Erie Station in Jersey City or in the waiting cars. Those with friends in the city stayed with them or at hotels. Prices went up for hotel rooms. Someone reported that an outrageous 25 cents were charged for a hard-boiled egg.

Wedding Postponed

Piermont Ave. looking toward Main St. Maloney’s Ale Vault on the left looks closed but two empty carriages stand in front of the Nyack House, a favorite watering hole. The three-story building on the left is a hotel.

On Monday, Hannah Hoffman realized that her Wednesday wedding to Herman Levy of Tarrytown that was scheduled for the Nyack Opera House would not be possible. It was postponed for a week until the day before spring. On a rainy March 20, the 2 were married. In 1938, the Journal News reported their 50th wedding celebration.

Blizzard Memories

It was said that in some places the snow remained until June. The Great Blizzard of 1888 may not hold the record for the area’s deepest snowfall, but it was such a memorable event that it registered with people for their entire lives and was noted every year in newspapers and as recently as 2017 by Robert Brum in the Journal News. Brum reported that it took weeks to clear away the snow since the only snow clearing equipment was a horse-drawn plow. It was more than a snow day; it turned out to be a snow week.

Michael Hays is a 35-year resident of the Nyacks. Hays grew up the son of a professor and nurse in Champaign, Illinois. He has recently retired from a long career in educational publishing with Prentice-Hall and McGraw-Hill. Hays is an avid cyclist, amateur historian and photographer, gardener, and dog walker. He has enjoyed many wonderful years with his beautiful companion, Bernie Richey. You can follow him on Instagram as UpperNyackMike.

Nyack People & Places, a weekly series that features photos and profiles of citizens and scenes near Nyack, NY, is brought to you by HRHCare and Weld Realty.

Nyack People & Places, a weekly series that features photos and profiles of citizens and scenes near Nyack, NY, is brought to you by HRHCare and Weld Realty.