by Mike Hays

Walking/biking path from Nyack Beach today was almost made into a twin auto highway.

“We certainly need it. I don’t see how there can be any opposition. Go to it and do it quickly.” This was Governor Al Smith talking about approving a 1923 plan to remove much of Hook Mountain to build 2 access roads through Upper Nyack for a new recreational park. It wouldn’t cost taxpayers anything since the mined rock from the mountain would be sold to pay for the roads. Intended to alleviate road congestion and crowding at the newly developed Bear Mountain State Park, the plan was developed by Major William A. Welch, chief engineer for the Palisades Interstate Park Commission (PIPC) since 1914. A pair of large one-way roads would connect “North Nyack” with Haverstraw along the shoreline. A shoreline route was an old idea dating back to when a railroad route that was to connect the Northern Railroad terminus in Nyack with points north was touted.

The Palisades

The dramatic riverside ridge that runs from Jersey City to Haverstraw where it turns inland, heading underground after Low Tor Mountain, is made of basalt formed by lava that once extruded through ancient sandstone rock. The Palisades appear on the Mercator map, the first European map of the New World based on a description by Verrazano who thought they looked like a “fence of stakes.” Palisades derives from the Latin word palus, or “stake.” Palisade was used to describe a defensive wooden wall. Native Americans used the term “Wee-Awk-En” to describe them, meaning “rocks that look like rows of trees.”

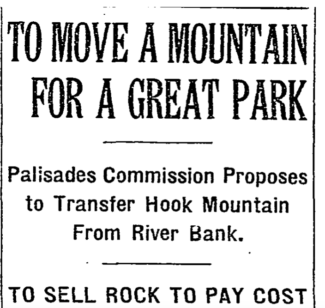

Quarries

The Manhattan Trap Rock quarry at Nyack Beach. The power house is bottom center and the plateau or working face is in the center.

Igneous rock has a number of properties that make it perfect for construction. Trap rock, a term used for small chunks of basalt, was ideal for making railroad beds, roads, and buildings. The term derived from the Swedish word “trappa” for stairway because of how it tends to cleave at right angles. The invention of dynamite provided the means to extract large volumes of rock from the Palisades. The rock face was dynamited, and the chunks of rock were crushed to make trap rock. The rock was loaded onto barges bound for Gotham.

The Palisades were first defaced soon after the Civil War by 20-foot painted signs for patent medicines across from New York City. By the 1890s, large quarries were opened. The famous Indian Head and George Washington rock formations in Fort Lee were removed in 1898. Objections to mining came from wealthy people who could see the defaced ridge from Wave Hill and Westchester mansions and by those who built mansion along the New Jersey ridge top. Faced with mounting threats, mine owners sped up operations to get as much trap rock removed as possible.

Quarries were opened at Rockland Landing (also known as Slaughter’s Landing), Hook Mountain in Upper Nyack, and Tallman Mountain near Piermont. Local millionaire Wilson Foss, a dynamite expert from Upper Nyack, held controlling interests in giant operations of the Manhattan Trap Rock Company at Rockland Landing.

Palisades Interstate Park Commission

Slightly reforested Nyack Beach in the 1930 after the bathhouse was built.

In 1900, the Palisades Interstate Park Commission was formed to preserve the Palisades from further development. J. DuPratt White of Upper Nyack was a founding member and held offices of secretary and president in his 40 years of service. The commission, using its banking and political connections, was able to cajole donations from the 1% of their day led by local billionaire families the Rockefellers, J. P. Morgan, and the Harrimans. Quarry owners fought the purchase of their operations tooth-and-nail, finally agreeing, but also arguing for a premium price. Wilson Foss sold his operation in 1908 and the operation at Nyack Beach was acquired in 1906, although quarrying didn’t cease until 1917.

The destruction caused by the quarries is shocking to today’s eye. The quarries were treeless scars along the entire rock face. At Nyack Beach, a shelf atop sandstone was created to allow for the cliff to be removed. The beautiful Nyack Beach Plateau is located on what was once the mining floor. Large rock chunks were taken by tram to a rock crusher located on the plateau edge. Crushed rock flowed downhill to an elevated tram that delivered rock to waiting barges. It has taken nearly a century for nature to reforest the cliffs and hide the scars.

Bear Mountain State Park: A Model for Hook Mountain

Passengers arriving at Bear Mt. docks on the Highlander.

In 1908, New York State acquired land near Bear Mountain with the intention of relocating Sing Sing Prison there. Work commenced. Meanwhile, PIPC was working with the Harriman family on a bequest of some 10,000 acres and $1M for the creation of a state park. The Harrimans demanded that a prison not be built, and work was ended. Steamship docks were built for easy access for day trippers. Facilities for picnics, hiking, and amusements attracted thousands. When automobiles became ubiquitous, day trippers overwhelmed the roads. 9W was still in its infancy, meandering through the villages of Rockland Lake Landing and Congers before getting to Haverstraw. The Nyack Ferry was jammed with car traffic even after the Bear Mountain Bridge was opened in 1924, built as the first Hudson River crossing to alleviate traffic jams at Bear Mountain.

The Hook Mountain Plan

There’s a long history of ideas for developing Hook Mountain. In 1870, the Boss Tweed “gang” once had a plan to build a hotel atop the mountain along with a large boulevard that was partially built to speed vacationers from New Jersey to the mountain top. In 1914, an early park planner proposed to drill a huge tunnel from Rockland Lake through the mountain to create a 160-foot waterfall. That idea didn’t get far, but it was an indication of things to come.

Schematic of the plan for Hook Mountain Beach.

The euphoria of potential riverside parkland that would create new park revenues at no cost drew Major William A. Welch’s attention. Welch was already busy building new lakes, roads, and children’s camps on the Harriman tract. Welch stated that another “playground” like Bear Mountain was needed. In the first half of 1923, 2 million visitors came to Bear Mountain via steamship and an average of 4,000 cars a day, 60% from New Jersey. New Yorkers avoided coming by car because of the congestion of the roads, “the cars just creep along,” Welch said. A couple one-way roads would be built through Upper Nyack along the river to Haverstraw.

In order to build roads, Hook Mountain’s edges would be “smoothed” out and space would be created by removing the mountain back to the deepest quarry excavations, thus recreating its former “natural state.” Welch calculated that some 10 million cubic feet of rock would need to be removed. The 10-year project would generate some $5 million worth of trap rock and therefore the project would pay for itself.

A Political Hudson River Cruise

Governor Al Smith ran twice for the US Presidency.

A decision regarding the project wasn’t made in a smoke-filled back room but in a large steamship liner, the Onteora. Some 350 dignitaries departed from New York City to tour the Palisades. Governors Smith for New York and Silzer of New Jersey were accompanied by State Senators and Assemblymen and the Park Commissioners on July 10, 1923. They stopped at the Bear Mountain Inn for lunch after which they went on a 70-mile trip in buses. They visited a Boy Scout camp at Lake Kanawauke where 2,500 boy scouts stood at attention for the governors. They visited Lake Stahahe, Storm King, and went onto West Point where they reviewed cadets.

Back on board the ship, Welch made his pitch using a plaster model to show how the new park would look. The Governors wholeheartedly approved the plan. Smith made the comment that, “The way to get those fellows to dig for nothing is to tell them King Tut is buried there.”

The governors saw a political plum. Hook Mountain was badly defaced, people wanted to be outdoors, and the project would pay for itself. Brooklyn congressmen pledged support; William Love promised to introduce the legislation in the next session.

Park Commission Comes Under Fire

The story of the proposed park broke in every newspaper in the region on July 11 with headlines like “Will Move Hook Mountain to Make Way for Palisade Park” and “Eager to Move Hook Mountain.” Reaction was not what the politicians thought it would be. Even the Park Commissioners took the heat. A letter was sent to the Park Commission by Joseph D. Holmes on July 16, to which DuPratt White responded the next day, claiming the park commission “cannot be held responsible for the what the newspapers talk about.”

The story of the proposed park broke in every newspaper in the region on July 11 with headlines like “Will Move Hook Mountain to Make Way for Palisade Park” and “Eager to Move Hook Mountain.” Reaction was not what the politicians thought it would be. Even the Park Commissioners took the heat. A letter was sent to the Park Commission by Joseph D. Holmes on July 16, to which DuPratt White responded the next day, claiming the park commission “cannot be held responsible for the what the newspapers talk about.”

He went on to explain that the commission “does not and never did intend to undertake quarry operations for the removal of Hook Mountain.” He explained that the plan would add accessible large playgrounds similar to Bear Mountain by “removal of the sharp contours and the softening of the scars left by the quarry.” And by the way, the crushed rock would pay for the park. White states that a plan had been around for years to build a highway along the river. The new development plan only amplified the original idea. White justified the plan by saying they would only remove part of the mountain.

The Zombie Road

The response must have been mirrored elsewhere as the public realized that one didn’t create a nature park by first destroying it. A letter to the editor in the August 23, 1923 New York Times addressing the issue of “improving” Hook Mountain suggested that the commissioners, while adept at land acquisition and management, knew little about landscape architecture and art, noting the problems with roads dynamited around Storm King and along Henry Hudson Drive in New Jersey. While the legislation for the Commission’s quarry does not appear to ever have been introduced, the idea of a road from “North Nyack” was a zombie idea, it kept coming back. In 1926, when development plans were announced for picnicking, camping, bathing and other amusements, there was still talk of building a riverside highway under the “frowning cliff of Verdrietege Hook.” Again in 1927, the zombie road plan was still afoot according to the New York Times. It is not even clear that the legislation was ever introduced.

The response must have been mirrored elsewhere as the public realized that one didn’t create a nature park by first destroying it. A letter to the editor in the August 23, 1923 New York Times addressing the issue of “improving” Hook Mountain suggested that the commissioners, while adept at land acquisition and management, knew little about landscape architecture and art, noting the problems with roads dynamited around Storm King and along Henry Hudson Drive in New Jersey. While the legislation for the Commission’s quarry does not appear to ever have been introduced, the idea of a road from “North Nyack” was a zombie idea, it kept coming back. In 1926, when development plans were announced for picnicking, camping, bathing and other amusements, there was still talk of building a riverside highway under the “frowning cliff of Verdrietege Hook.” Again in 1927, the zombie road plan was still afoot according to the New York Times. It is not even clear that the legislation was ever introduced.

Hook Mountain and Nyack Beach State Parks

Hook Mountain Beach in the 1940s showing a natural sand beach, wading pool, and children’s playground.

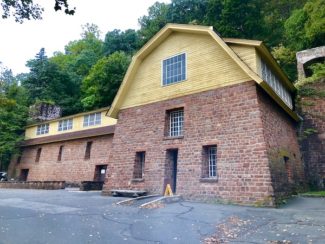

A revised $100,000 park plan was announced in 1928. At Hook Mountain Beach, a steamboat dock would be built out to where the river was 14 feet deep. A large luncheon pavilion would be built on the pier. A large bathhouse was to be built fronting a natural sand beach. A cafeteria, dance hall, and amusement rides were added along the shoreline. The plateaus were cleared of rock and made into ballfields, running tracks, picnic facilities, and tennis courts. The zombie road through Upper Nyack was gone from the plan, instead the steep road down the cliff alongside the old ice train track, was to be improved.

Much of the work was completed through 1930s government-fundied work relief programs including refacing the concrete powerhouse into a sandstone-faced bathhouse at Nyack Beach. The park at Hook Mountain Beach was completed with dancehall, amusement rides, beach-side playground, a new road from Rockland Lake, and a cafeteria-hotel. Both parks were severely damaged by a major storm in 1950, Hook Mountain Beach was never restored. Attention was diverted from the beaches to acquiring and developing Rockland Lake State Park from 1958 to 1964. Today, an attentive hiker might find the remnants of Hook Mountain beach buildings and the plateau ballfields.

One shudders at the thought of a divided highway passing through Upper Nyack along with a diminished Hook Mountain. It was a near miss from the governor’s backing and pronouncement to “go to it and do it quickly.”

See Also:

- Nyack People & Places: Barons of Broadway–Under Elms

- Nyack People & Places: James Lyon, Hudson River’s Oldest River Captain

- Nyack People & Places: Why No Sidewalks on N. Midland?

- Nyack People & Places: Long Lost Hook Mountain Beach

- Nyack People & Places: When Nyack Beach Was A Beach

Michael Hays is a 35-year resident of the Nyacks. He grew up the son of a professor and nurse in Champaign, Illinois. He has recently retired from a long career in educational publishing with Prentice-Hall and McGraw-Hill. He is an avid cyclist, amateur historian and photographer, gardener, and dog walker. He has enjoyed more years than he cares to count with his beautiful companion, Bernie Richey. You can follow him on Instagram as UpperNyackMike.

Nyack People & Places, a weekly series that features photos and profiles of citizens and scenes near Nyack, NY, is brought to you by Sun River Health, and Weld Realty.

Nyack People & Places, a weekly series that features photos and profiles of citizens and scenes near Nyack, NY, is brought to you by Sun River Health, and Weld Realty.