by Juliana Roth

by Juliana Roth

“Oh it’s a wonderful painting. People in New York know it very well because it was on the cover of the New York phone book,” says Edward Hopper’s biographer, Gail Levin, in reference to his 1930 painting Early Sunday Morning. “We have the feeling that we’re looking down on the street scene from maybe a second story window across the street and what might have inspired him was in fact he saved his ticket stubs from Elmer Rice’s play Street Scene that he saw in December 1929.” Rice often wrote about the intersecting lives of New Yorkers through linked vignettes. Street Scene is set entirely on the stoop of a brownstone.

“Trees look like theater at night,” Hopper said of his landscape compositions. The trees in the backyard of the Edward Hopper House often cast shadows on the film screen that’s been out of use now for months.

Ideas of staging, performance, and cinematic tension were observed by Hopper in the rare moments he spoke about his work. “Being very frugal, which Hopper and his wife were probably due to their long years of struggle, they sat in the second balcony and they looked down on Joe Mielziner’s set for Street Scene,” Levin continues. Edward and Jo, watching. Observing what the playwright constructed, what the designer imagined, the familiar landscape of their city. What did it feel like to see their watching performed on stage? What did it mean for them to now be in the audience? Was that much different than the time spent in Washington Square Park glancing up from newspapers or driving through towns on their way up the coast?

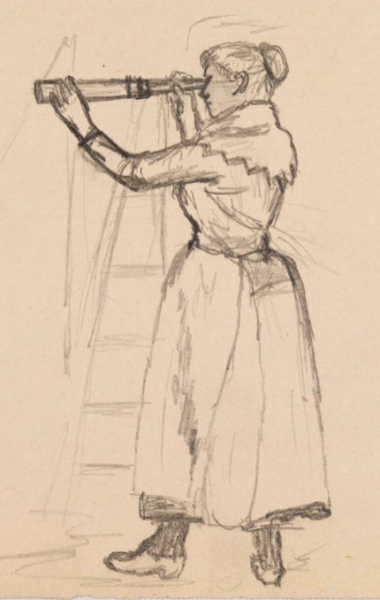

Jo kept Edward’s records, making notes about his paintings and his process. They often cycled through names, color schemes, and other essentials of the visual storytelling in these notes. They even, at times, named the painting’s characters. The woman in Intermission was called Nora.

Many of Edward’s paintings feel as though they are characters waiting for something to happen, or hiding from, or recovering after. As Tom Waits describes Nighthawks in his album written after the painting, they depict “a melodramatic nocturnal scene.” Perhaps that’s why so many artists, along with Waits, bring Edward Hopper into their own creative processes.

Lawrence Block edited an entire anthology of work inspired by Edward Hopper, In Sunlight Or in Shadow, commissioning fiction from Craig Ferguson, Megan Abott, Joyce Carol Oates, and Stephen King, among many others. King is one of several artists who deal with horror, surrealism, and paranoia to write directly about Edward Hopper. There’s a well supported rumor that Hitchcock’s Psycho was inspired by The House by the Railroad.

While Hitchcock didn’t state this directly, he was known to collect art (Picasso, Klee, Rouault) and collaborate on other films with painters, like Dalí. At the very least, the painting was likely used, or in the dream of, the Bates Motel and house made by set designers Joseph Hurley and Robert Clatworthy, which later inspired a Cornelia Parker exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Other directors, like Jim Jarmusch and David Lynch, cite Edward Hopper as an influence.

Most recently, Wim Wenders, installed a 3D film at the Fondation Beyeler in Basel, Two or Three Things I Know About Edward Hopper. Wenders notes that The American Friend, The End of Violence, and Don’t Come Knocking were inspired by a study of Hopper’s work. All reverberations from a single moment. From what one eye saw of a life, reported on, read, drew, recreated, then made again anew.