by Juliana Roth

by Juliana Roth

As I begin to read Marion Hopper’s 1936 journals, I’m struck by the design. The style of her journal positions a countdown at the top of the page: “143rd Day—223 Days to Follow.” The first time I saw this, in the fall of 2019, the idea of counting down a year made me feel sorrow. Though I date my own journal entries and keep a regular planner for each day of the week, the idea of being reminded daily of how much time I had left in a year felt like an unwelcome reminder that life is finite.

The tallying of days in this way is also something that would have likely caused anxiety for me at other times of my life: an impending thesis deadline for graduate school, the hours left until my next shift at work—or maybe I’m being unfair and the countdown could’ve been towards something delightful such as a trip to visit a friend or a movie release. After having spent the better half of this year in quarantine, the demarcation of time spent and time left in a year takes on a new meaning, opening a window for me to peer in and see Marion Hopper and her daily recording anew.

Marion spent the majority of her days inside 82 N Broadway in Nyack. Her daily routine: send out letters, tend to the home, care for her mother. In her journals, she often refers to her chores, the weather, an occasional social exchange. One moment in particular stands out to me, that in the spring of 1936 she helped to serve ice cream and cake after a recital alongside mothers of the children who’d performed after which she describes herself feeling “down, down, down.”

“In the basement there was a big central hot air furnace, big round tin thing with octopus branches coming out to feed into the registers in the floor, and next to it was an empty coal bin, coal had been delivered and put into the furnace. At the end of her lifetime, there was no coal left, but there were broken chairs, pieces of chairs, that she had fed into her furnace, so she must have been living in what we call genteel poverty here,” says Win Perry, local historian and activist who was a central figure in restoring and saving what largely served as Marion’s home, and who remembers an occasion of entering the home while Marion lived here. This a reality many elderly populations continue to face, compounded by the isolation of quarantine. “I feel I will go crazy worrying about money,” Marion writes.

Her attention is often on money and the condition of the house. She is self-referential about her familiar preoccupations and concerns, noting her own conflicting feelings about having the luck of a house to worry after and the distraction of the worry itself: “I suppose I’ve made too much of an idol of my house. It is a refuge.”

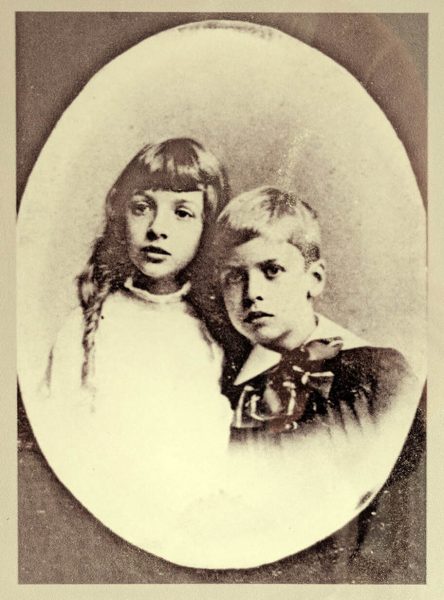

While Edward Hopper is being newly described as the “artist of the quarantine,” others argue that Edward’s work wouldn’t exist without being able to walk freely about Manhattan or traveling with ease for the rural scenes he painted, that the paintings themselves serve more to explore such emotive connections to others and place. Though his works inspire solitary reflection, perhaps the true figure of quarantine in the Hopper family was Marion herself. Afterall, she was the one who modeled the import of the daily log, of recording what feels mundane as time passed, of noticing the small moments and correspondences that make an isolated day worth bearing.

Juliana Roth is a writer from Nyack, NY and serves the Chief Storyteller with EHH.

This series exploring the Edward Hopper archives is a collaboration between Nyack News & Views and Edward Hopper House Museum & Study Center.