by Mike Hays

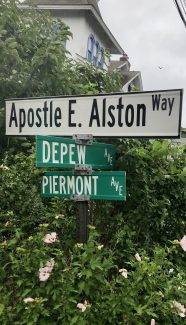

Street sign at the foot of Depew Ave.

Claus, Flas, Dick, Cuff, Pompey, and Dick. Say their names, for they were enslaved people purchased by Orangetown landowners Peter and Tunis DePew from 1795-1810. Of the six, four were purchased after the Gradual Abolition Act of 1799 was passed, a testament to the fact that slavery was more widespread in Orangetown than historians once admitted.

Consider this: History of Rockland County author Frank Green writes that “the slaves were never numerous, and the custom was never popular.” And yet, 45% of homesteads in Orangetown in 1800 owned enslaved people. The average number of the enslaved per slave-owning household was 2.7. While the average does not approach that of the huge southern slave plantations of 1800, slavery was nonetheless widespread in Rockland County, Orangetown, and even in downtown Nyack.

Grim reminders of slavery are found today in several Nyack streets named after wealthy owners of enslaved people: Cornelison, Tallman, and Depew, and Lydecker (not to mention the commemoration of national figures like Washington and Jefferson). Slavery was an accepted way of life in 1800 in Nyack, as it was in much of America. A snapshot of the DePew family, once owning the highest taxable property including the enslaved in Orangetown, gives a glimpse into a Nyack that’s little discussed–but that should be.

Slavery in Orangetown and Nyack in 1800

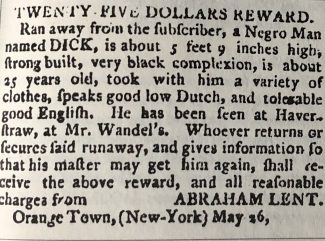

1796 runaway ad for Dick, an enslaved man owned by Abraham Lent.

Orangetown was a sparsely populated rural town in 1800. Nyack was composed of about 10 relatively large farms along with a few houses in what is now downtown Nyack. Slavery would have been visible to everyone because nearly half of all homes owned enslaved people.

Slaves were expensive. Men would sell for $250, about the price of 10 acres of land; women for $65; and children for about $30. With additional land being cleared and labor in short supply, farmers depended upon slavery to work their farms. The expense of those they owned argued for an unwillingness by farmers to part with assets and manumit those they owned.

Most of the leading families of Orangetown owned enslaved people in 1800. Abraham Lent had 10, the most in Orangetown. Lent was sent to the first Congressional Congress in 1775 from Orange County and served as a colonel in the Rockland militia during the Revolutionary War. In 1795, Lent advertised a $25 reward for return of Dick, who had run away. Dick spoke Dutch and tolerable English. Samuel Verbryck, Orangetown Supervisor for many years in the early 1800s, owned 6 in 1800. Most of Nyack’s 10 farms owned enslaved people during the period, including the Cornelisons, DePews, Harts, Lydeckers, Sarvents, Williamsons, and Smiths.

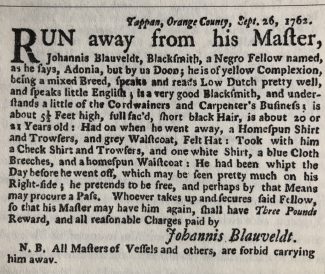

The 19th century historian David Cole states that in Rockland County, “the slaves, [were] never treated with severity, and always attended church with their owners,” albeit seated in a segregated section from which they were lectured to obey their masters. As to severity of their treatment, a 1762 newspaper ad by Johannis Blauvelt seeking the capture of a runaway named Adonia openly states the opposite: “he had been whipt the day before he went off, which pretty much may be seen on the right side.”

DePew’s Nyack Estate

1859 map of Nyack showing the large Depew farm. Nyack Brook is clearly visible with one mill pond still visible. Broadway does not extend beyond Depew Ave. Liberty School and the Presbyterian Church are shown in blue.

Petrus DePew (also spelled “De Puy”) purchased 80 acres of prime Nyack riverfront land in 1791. The property boundaries ran from 1,000 feet offshore on the east to 9W on the west, and from Depew Ave. on the north to Hudson Ave. on the south. Nyack Brook ran through the eastern part of the bucolic property and a grove of trees populated the western side. A couple mill ponds on either side of Broadway drove a grist mill located where the brook meets the Hudson River in Memorial Park. The DePew family also owned a grist mill on their Hackensack River property. Tunis bought more property to the north and south. The southern boundary eventually reached to what is now Division Ave., where it bordered the Voorhis estate.

The DePew Family

The DePew family history reads like a classic American success saga. Two Huguenot brothers from Normandy immigrated to America in the 1660s. Willem, from the second generation, owned a farm at Verplanck’s Point in Westchester. Pieter, from the third generation, being the youngest son of Willem and not inheriting much, acquired a farm near Hackensack Creek in an area then called Schreclaw, now Orangeburg. Pieter, born in 1703, lived to experience British marauders in the Revolutionary War, escaping once by hiding in the chimney of his mill.

The Depew house built in the 1850s by Peter Depew, son of Tunis, the original land owner.

One of Pieter’s sons, Petrus DePew, born in 1723, took over the farm and served in the Revolutionary War. Among his children were two sons, Peter (every generation seems to have a son named Peter) and Theunis (usually spelled today as “Tunis”). Peter took over the family farm along the Hackensack, and Tunis Van Dolsen DePew, as he was known, settled on the Nyack property. In addition to the grist mill, Tunis started a quarry on the property, built the first dock in Nyack (presumably at the foot of Depew Ave.), and deeded the land for a Presbyterian church (now the Nyack Center) in 1816.

Tunis’ son, Peter Depew, was able to expand on Tunis’ successes into a shipping business and a nursery business growing grapevine stock. He deeded some of his land for Liberty School in 1852, was active in management of the Rockland Female Institute, and was instrumental in bringing the railroad to Nyack, deeding part of the grove of trees on his property for the Nyack train station. To confuse matters further, one of his sons was named Tunis, and he took over the family estate after his father’s death and was also prominent in Nyack business and real estate development.

The Enslaved

Runaway ad seeking the return of Adonia owned by Johannis Blauvelt. He had good reasons to run, he was badly whipped the day before.

The original deeds

for six enslaved people purchased by brothers Tunis and Peter were given to the Association of Blauvelt Descendants passing through several curatorial hands. According to a record of the deeds:

- Peter DePew purchased

- Pompey for 80 pounds in 1795 from Jacob van Wagner of Bergen to serve a term of 80 years.

- Dick, age 23, for $275 in 1806 from Peter Van Orden in Clarkstown.

- Claus, age 42, for 100 pounds in 1802 from David Boget (Bogart?). Flas, a “negro wench” was an add-on “gift.”

- Tunis DePew purchased

- Dick, age 8, for $135 in 1806 from Andries (Aury?) Smith, Clarkstown.

- Cuff, age 48, for $165 in 1810 from Robert Stephens, Clarkstown.

In New York State, 1799’s Gradual Abolition Act meant that those enslaved born before 1799 were to remain enslaved for life and that those born after would serve 28 years. Total emancipation occurred in 1827. No record exists of the post-abolition lives of those enslaved by DePew.

After abolition, most of those freed left Orangetown. According to Carl Nordstrom’s Nyack in Black and White, the total number of African-Americans declined in the 1830s: 35% of those who remained worked and lived in white households. Few former enslaved people found independent ways to earn a living in Nyack, although there were some exceptions: Peter Williamson, a shop keeper in Upper Nyack; Samuel Freeman, a basket maker; and John Sarvent, a ship’s carpenter.

Nyack Street Names

Street marker for Hesdra Way on Piermont Ave. at Hudson Ave. near the Depew house.

The Black Lives Matter movement has brought founders’ slave holding to the fore. Some even suggest changing the name of the Jefferson Memorial. As with our country’s founders, so with Nyack’s founders. What are we to make of streets named after slave owners? How do we reckon with the fact that many of our farms, quarries, mills, ships, and fields thrived as a result of slave labor?

In part, an answer exists at the foot of Depew Ave. Above the street sign is a marker identifying Apostle E. Alston Way. Apostle Dorain Elizabeth Alston, who passed in 2019, was the African-American founder of the St. John Deliverance Tabernacle located nearby in 1965. The marker replaces that of Cynthia Hesdra Way that has moved to a more correct historical location a block away, Hesdra being an African-American land holder and probable manager of the Underground Railway in Nyack.

We can’t change the cultural life of 1800 but it is important that we recognize the time for what it was, a stain on our founding creed that all men are created equal. We can do better. And celebrating the lives of African-Americans then and now is one small forward step.

See Also

- Nyack People & Places: The Last Living Person Born into Bondage in Rockland County

- Nyack People & Places: Was Nyack Brook a Landmark on the Underground Railroad?

Sources

Nyack In Black & White, Carl Nordstrom, 2005

Slavery in New York, Berlin & Harris, eds, 2005

The Depew Family, unattributed and undated, The Nyack Library

Michael Hays is a 30-year resident of the Nyacks. Hays grew up the son of a professor and nurse in Champaign, Illinois. He has recently retired from a long career in educational publishing with Prentice-Hall and McGraw-Hill. Hays is an avid cyclist, amateur historian and photographer, gardener, and dog walker. He has enjoyed more years than he cares to count with his beautiful companion, Bernie Richey. You can follow him on Instagram as UpperNyackMike.

Nyack People & Places, a weekly series that features photos and profiles of citizens and scenes near Nyack, NY, is brought to you by HRHCare and Weld Realty.

Nyack People & Places, a weekly series that features photos and profiles of citizens and scenes near Nyack, NY, is brought to you by HRHCare and Weld Realty.