by Bill Batson

by Bill Batson

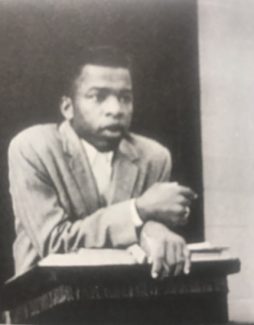

The light of a life lived to its fullest is never extinguished. From February 21, 1940 until July 17, 2020, Congressman John Lewis dedicated virtually every step he took to the moral advancement of the United States. At our darkest hours, he march into the most perilous places, armed only with the philosophy of nonviolence and a fierce determination to make America honor the creeds enshrined in our founding documents. In death, the legacy of John Lewis becomes one of our nation’s brightest beacons of hope.

At the time of his death, there are protests in 50 states demanding the final removal of the systemic racial discrimination Lewis fought his life to end. As Lewis closed his eyes to rest, in peace and power, he must have been confident that a new generation of activists had taken up his mantle.

Elected to the House of Representatives from Atlanta, Georgia in 1987, Lewis came to be known as the conscience of the United States Congress. Born to sharecropping parents in rural Alabama, Lewis’ piety earned him the childhood nickname “Preach” and eventually led him to the American Baptist Theological Seminary in Nashville, Tennessee. He joined the sit-on movement while at Nashville’s Fisk University where he apprenticed with the legendary Reverend James Lawson, who studied non-violence and passive resistance in India with Mahatma Gandhi.

Elected to the House of Representatives from Atlanta, Georgia in 1987, Lewis came to be known as the conscience of the United States Congress. Born to sharecropping parents in rural Alabama, Lewis’ piety earned him the childhood nickname “Preach” and eventually led him to the American Baptist Theological Seminary in Nashville, Tennessee. He joined the sit-on movement while at Nashville’s Fisk University where he apprenticed with the legendary Reverend James Lawson, who studied non-violence and passive resistance in India with Mahatma Gandhi.

In 1963, Lewis was elected Chair of the Student Non-violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). As SNCC’s leader, Lewis was nearly removed from a speaking slot at the March on Washington because of the radical content of his speech. Two years later, he was nearly martyred on the Edmund Pettus Bridge during the Selma-Montgomery March. Immortalized as “Bloody Sunday” that march led directly to the passage of the Voting Rights Act.

Speaking on CNN about his movement colleague of many decades, Ambassador Andy Young, Dr. Martin Luther king Jr.’s lieutenant and confidante, said, “We were all serious, John was more serious. We were all courageous. John was more Courageous.”

Lewis passed the same week we lost another member of Dr. King’s leadership team, C.T. Vivian, who was known as King’s Field Marshal.

Lewis passed the same week we lost another member of Dr. King’s leadership team, C.T. Vivian, who was known as King’s Field Marshal.

There are two factors that one must appreciate in order to understand the life of John Lewis, how extremely young he was when he became an activist and how extremely dangerous and formidable were the forces that opposed his activism.

To all the young people who have found purpose in protest over the last three months, and all the adults who cannot transcend their skepticism, here are some words from John Lewis to inspire us to “make good trouble!”

“I could not live the way they did.” 1955 – John Lewis at 15.

“I was shaken to the core by the killing of Emmett Till. I was fifteen, black, at the edge of my own manhood, just like him. He could have been me. That could have been me, beaten, tortured, dead at the bottom of a river. It had been only a year since I was so elated at the Brown decision. Now I felt like a fool. It didn’t seem that the Supreme Court mattered. It didn’t seem that the American principles of justice and equality I read about in the beat-up civics book at school mattered.

“I was shaken to the core by the killing of Emmett Till. I was fifteen, black, at the edge of my own manhood, just like him. He could have been me. That could have been me, beaten, tortured, dead at the bottom of a river. It had been only a year since I was so elated at the Brown decision. Now I felt like a fool. It didn’t seem that the Supreme Court mattered. It didn’t seem that the American principles of justice and equality I read about in the beat-up civics book at school mattered.

By the end of that year (1955) I was chewing myself up with questions and frustrations and, yes, anger – anger not a white people in particular but at the system that encouraged and allowed this kind of hatred and inhumanity to exist. I couldn’t accept the way things were, I just couldn’t. I loved my parents mightily, but I could not live the way they did, taking the world as it was presented to them and doing the best they could with it.

But as I began to come of age in the mid-1950s, the landscape had begun to shift. The time had come. I could feel it, I could see it.

And in December of that landmark year, 1955, I saw it just up the highway in Montgomery, where that man, the Reverend Dr. Martin Luther KingJr., took the words I’d heard him preach on the radio and put them into action in a way that set the course of my life from that point on. With all that I have experienced in the past half century, I can still say without question that the Montgomery bus boycott changed my life more than any other event before or since.”

And in December of that landmark year, 1955, I saw it just up the highway in Montgomery, where that man, the Reverend Dr. Martin Luther KingJr., took the words I’d heard him preach on the radio and put them into action in a way that set the course of my life from that point on. With all that I have experienced in the past half century, I can still say without question that the Montgomery bus boycott changed my life more than any other event before or since.”

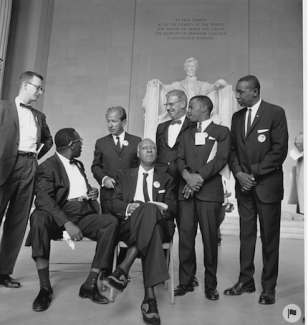

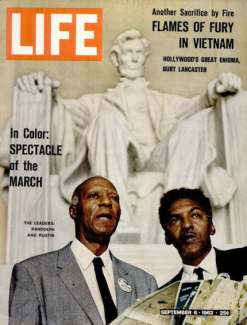

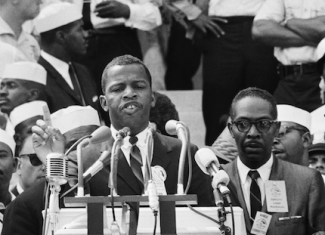

March on Washington, 1963 – John Lewis at 23

“Exactly one week after being elected Chairman of SNCC, here I was, at the White House, meeting with John F. Kennedy, meeting Bobby Kennedy, meeting Lyndon Johnson. The President was due to leave for Vienna the next day to meet Khrushchev – their first meeting since the previous October’s Cuban Missile Crisis – and he came into the room in somewhat of a hush. He shook hands all around the table, greeting us each with a “Hello.” No names. Bobby sat over by a wall, with one of his daughters in his lap. There were other people around, watching over the proceedings and taking notes.

“Exactly one week after being elected Chairman of SNCC, here I was, at the White House, meeting with John F. Kennedy, meeting Bobby Kennedy, meeting Lyndon Johnson. The President was due to leave for Vienna the next day to meet Khrushchev – their first meeting since the previous October’s Cuban Missile Crisis – and he came into the room in somewhat of a hush. He shook hands all around the table, greeting us each with a “Hello.” No names. Bobby sat over by a wall, with one of his daughters in his lap. There were other people around, watching over the proceedings and taking notes.

…

Despite all that anxiety we felt fairly calm, thanks to Bayard [Rustin’s] attention to details. All in all, things looked well in hand. Which is how we wrapped up that day, and which was how I felt as I returned to my room late that night. That’s why I was surprised to find a handwritten note that had been slipped under the door while I was out.”

“John,” it read, “come downstairs. Must see you at once.”

“John,” it read, “come downstairs. Must see you at once.”

It was signed by Bayard.

Almost as soon as I read it, the phone rang. Bayard’s voice was on the line.

“We have a problem,” he said….”It’s your speech.”

Someone [had] picked up a copy [of my speech] and rushed it over to Washington’s Archbishop Patrick O’Boyle, who was to deliver the event’s opening invocation the next day. O’Boyle was so horrified by what he considered the inflammatory tone of my words that he contacted the White House – Burke Marshall, specifically. Then O’Boyle called Rustin and said he would have nothing to do with the event if I was allowed to deliver this speech.

….

Bayard Rustin

As the time drew near for me to take the stage, there was still a battle going on over my address. A. Philip Randolph had returned to the room. Rustin was there. A long list of objections and concerns had been scribbled. But now I wasn’t the only one they were dealing with. Courtland Cox and Jim Forman had gotten wind of what was happening and had made their way back to the tiny office. They were hot. If one word of this speech was changed, they told Bayard, it would be over their dead bodies.

It looked as if no one was going to budge. Then Randolph stepped in. He looked beaten down and very tired.

“I have waited twenty-two year for this,” he told us. “I’ve waited all my life for this opportunity. Please don’t ruin it.”

Then he turned to me.

Then he turned to me.

“John,” he said. He looked as if he might cry. “We’ve come this far together. Let’s stay together.”

This was as close to a plea as a man as dignified as he could come. How could I say no? It would be like saying no to Mother Theresa.

I said I would fix it. And so Forman sat down at a portable Underwood typewriter in that little room, and I stood beside him as we talked through every sentence, every phrase. We could hear the crowd beyond the statue as we worked through the changes and Forman typed them out.

Cut were the words that criticized the President’s bill as being “too little and too late.”

Cut were the words that criticized the President’s bill as being “too little and too late.”

Lost was the call to march “through the heart of Dixie, the way Sherman did.”

Gone was the question asking, “Which side is the federal government on?”

The word “cheap” was removed to describe some political leaders, though the phrase “immoral compromises” remained as did “political, economic and social exploitation.”

I was angry. But when we were done, I was satisfied. So was Forman. The speech still had fire. It still had bite, certainly more teeth than any other speech that day. It still had an edge, with no talk of “Negroes” – I spoke instead of “black citizens” and “the black masses,” the only speaker that day to use those terms.

The address that the March on Washington is commonly known for is Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s “I have a Dream” speech.

(adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({});

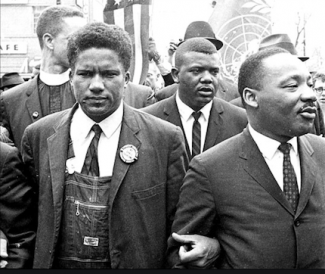

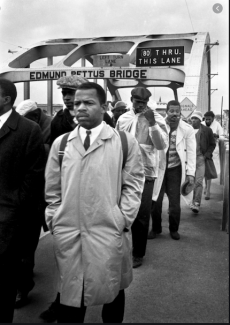

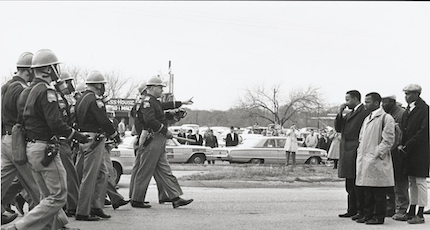

Selma-to-Montgomery March, 1965 – John Lewis at 25

I can’t count the number of marches I have participated in during my lifetime, but there was something peculiar about this one. It was more than disciplined. It was somber and subdued, almost like a funeral procession. No one was jostling or pushing to get to the front, as often happened with these things. I don’t know if there was a feeling that something was going to happen, or if the people simply sensed that this was a special procession, a ‘leaderless’ march. There were no big names up front, no celebrities. This was just plain folks moving through the streets of Selma,

I can’t count the number of marches I have participated in during my lifetime, but there was something peculiar about this one. It was more than disciplined. It was somber and subdued, almost like a funeral procession. No one was jostling or pushing to get to the front, as often happened with these things. I don’t know if there was a feeling that something was going to happen, or if the people simply sensed that this was a special procession, a ‘leaderless’ march. There were no big names up front, no celebrities. This was just plain folks moving through the streets of Selma,

There was no singing, no shouting – just the sound of shuffling feet. There was something holy about it , as if we were walking down a sacred path. It reminded me of Gandhi’s march to the sea. Dr. King used to say that there is nothing more powerful that the rhythm of marching feet, and that was what this was, the marching of a determined people. That was the only sound you could hear.

When we reached the crest of the bridge, I stopped dead still.

When we reached the crest of the bridge, I stopped dead still.

There, facing us at the bottom of the other side, stood a sea of blue helmeted, blue uniformed Alabama State troopers, line after line of them, dozens of battle-ready lawmen stretched from one side of U.S. Highway 80 to the other.

Behind them were several dozen more armed men – Sheriff Clark’s posse – some on horseback, all wearing khaki clothing, many carrying clubs the size of baseball bats.

Behind them were several dozen more armed men – Sheriff Clark’s posse – some on horseback, all wearing khaki clothing, many carrying clubs the size of baseball bats.

On one side of the road, I could see a crowd of about one hundred whites, laughing and hollering, waving Confederate flags. Beyond them, at a safe distance, stood a small, silent group of black people.

It was a drop of one hundred feet from the top of that bridge to the river below. Hosea Williams glanced down at the muddy water and said, “Can you swim?”

“No,” I answered…

I noticed several troopers slipping gas masks over their faces as we approached….

I noticed several troopers slipping gas masks over their faces as we approached….

“We should kneel and pray,” I said to Hosea.

He nodded.

We turned and passed the word back and began bowing down in a prayerful manner.

But that word didn’t get far. It didn’t have time…

..then all hell broke loose.’

According to the National Archives, “one minute and five-seconds after a two-minute warning was announced, the troopers advanced, wielding clubs, bullwhips, and tear gas. John Lewis, who suffered a skull fracture, was one of fifty-eight people treated for injuries at the local hospital”

Many credit this march, and the subsequent procession that made in to Montgomery, with the passage of the 1965 Voting Rights Act.

Black Lives Matter, John Lewis is 80

Black Lives Matter, John Lewis is 80

Standing on a building above the Black Lives Matter mural painting the street of Washington, D.C. that leads to the White House, Lewis had words for those that staging protests that continue the work of perfecting our democracy.

“You only pass this way once, you gotta give it all you can.”

“You must be able and prepared to give until you cannot give any more. We must use our time and our space on this little planet that we call Earth to make a lasting contribution, to leave it a little better than we found it, and now that need is greater than ever before.”

A documentary on the life of John Lewis, Good Trouble, premiered this month

Childhood, March on Washington and Selma -Montgomery March quotes come from Walking with the Wind, a Memoir of the Movement by John Lewis with Michael D’Orso. The Black Lives Matter quotes come from Washington Post Editorial Board Member Jonathan Capehart.

Consider supporting the Nyack Sketch Log!

If you have enjoyed my column at any point during the last nine years, I ask that you support the continuation of the Nyack Sketch Log by visiting nyackgift.com and consider acquiring or sharing one of my books or some of my merchandise.

As one of Nyack’s smaller businesses, I thank you for your past support and hope to continue to provide the people of the village that I love illuminating illustration and edifying essays long into the future.

Donations are also welcome through paypal via wrbatson@gmail.com

Bill Batson is an activist, artist and writer who lives in Nyack, NY. “Nyack Sketch Log: John Lewis 1940 – 2020 Resting in Peace and Power ” © 2020 Bill Batson. ” Learn more about Bill at billbatsonarts.com.