by Juliana Roth

by Juliana Roth

We might assume the ways Edward Hopper’s Baptist upbringing influenced his relationship to desire. Nicolas Cendo of Musée Cantini facilitated the French museum’s Edward Hopper exhibition in 1989. Cendo’s essay on Hopper’s work was written at the time of the first exhibition of Hopper’s paintings in France and southern Europe, allowing for displays in Marseilles and later in Madrid. The exhibition was a significant event in the international engagement with Hopper’s work. Cendo writes of Hopper’s use of light, that it was a means of showing “the restrained, almost buried, human dimension in which desire, melted down and recast in his paintings, opposes ever more intensely the implacable isolation to which the world condemns it.”

As someone who rather likes time alone, and as someone who has on many occasions gone to great lengths to find such solitude, I resist interpreting Hopper’s scenes or lifestyle simply as lonely or exiled, which is often the way they’re responded to. Especially as someone, like Hopper, who was born and raised in Nyack, NY with multiple generations of family history in the town (the childhood home from where I write these essays is only a one minute walk downhill from Hopper’s), Nyack offers to me a compelling space for such solitude–it is even encouraged. Across the street from my house is the Hudson River and the sites of the shipyards where young Hopper learned to rig yachts and where, it’s been reported through local lure, Hopper would oftentimes set up an easel to paint. If you let it, the Hudson River has a lot to teach you about being an observer of light, and when you walk alone alongside the water, there is a sense you are in conversation.

Still, it might be inaccurate to interpret Hopper’s paintings as not portraying isolation, and a bit self-indulgent of me to assume my experience of Nyack could inform us as to what Hopper felt. As I grew up, there was (and continues to be) a thriving downtown, film crews who regularly set up shop on the streets, and a connective community of artists available to people of all ages–along with some persistent commercialization. When Hopper was a child at the end of the Victorian era, Nyack had a population of 4,000, which today is nearly doubled. His world as a young man would have offered little choice in encountering solitude and silence on a daily basis, but was also marked with a rumbling that something else existed beyond the town as Nyack continued to industrialize.

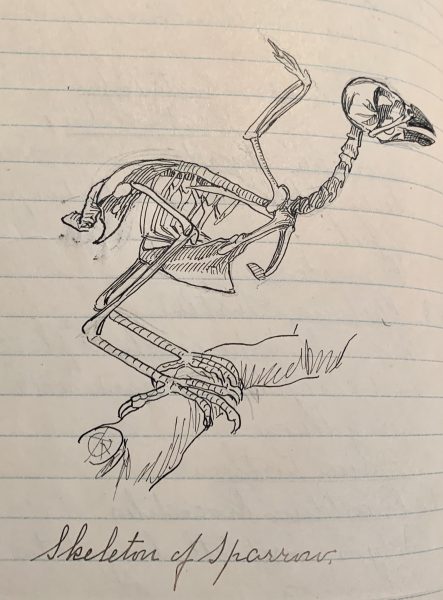

This sketch of the sparrow produced by young Hopper in the late 1800s looks at the internal structure of a somewhat common bird. Sparrows are birds who’ve populated the farthest globally. They are highly social and often nest together or form flocks with birds of other species, chirping along with their roost. They bathe in groups. They hop instead of walk. They form lifelong couples. Rarely do they live more than a few miles from where they were born, though some sparrows do migrate. Birders in the Hudson River Valley report thousands of observations of the bird, but some sparrows are listed as threatened populations in the state.

This sketch of the sparrow produced by young Hopper in the late 1800s looks at the internal structure of a somewhat common bird. Sparrows are birds who’ve populated the farthest globally. They are highly social and often nest together or form flocks with birds of other species, chirping along with their roost. They bathe in groups. They hop instead of walk. They form lifelong couples. Rarely do they live more than a few miles from where they were born, though some sparrows do migrate. Birders in the Hudson River Valley report thousands of observations of the bird, but some sparrows are listed as threatened populations in the state.

Throughout his life, Edward was drawn to the idea of France. He often wrote himself into the narrative of belonging to the country, especially when referring to the origins of his great grandfather, Reverend Joseph W. Griffiths, who organized the Baptist congregation in Nyack in 1854 with the founding of Nyack’s first church (which still stands at 140 N. Broadway), as having “married a French girl…when he came to America.” When Hopper spoke about his heritage, he often cited his Frenchness. He might be remembered withing the realism movement, but of himself, he said, “I think I’m still an impressionist. He was drawn to the work of the Impressionist artwork he saw in Paris. During his time there, Hopper created some of his brightest, lightest works.

First Baptist Church

Upon returning from France, it makes historical sense–with all of Hopper’s longings and curiosities–that he joined the artists in the “revolt from the village” by moving from Nyack in 1910 to Greenwich Village; what becomes routine or regular we perhaps long to escape. It also makes historical sense that his older sister Marion, who also exhibited an interest in the arts at a young age, stayed behind and spent her life as a caretaker of both the house and their mother. A similar dynamic emerged with Hopper’s wife, Jo, who wrote in her diary, “Of course if there can be room for only one of us, it must undoubtedly be he. I can be glad and grateful for that.” Though much of Hopper’s acclaim came later in his life and after his death, the world was ready for Hopper and he for it.

Along with Hopper’s boyhood artifacts and early sketches, what we have in our archive is what’s left behind by Marion, which tells an important story alongside the trajectory of Hopper himself, one that restores the full history of Hopper’s domestic life, the full history of our museum, and one that I will soon start to share in these dispatches.

A few years before Hopper moved away from Nyack, he arrived in France for the first of three visits, and his relationship with light began to evolve. “The light was different from anything I had ever known. The shadows were luminous–more reflected light. Even under the bridges there was a certain luminosity,” Hopper said of the experience. Yves Bonnefoy, a French curator, describes Hopper’s gaze as having been “cleansed of its shadows” by spending time in Europe.

Cendo goes on to describe how often barriers in Hopper’s work disappear and the viewer is welcomed into silence, into whatever underlying desire is present in the piece. The desire in Hopper’s work is seen as “absolute” and “eternally remote,” even a means to conceal an “immense wound.” Painting may have emerged within young Hopper as a sort of search, a way to form an active connection to the experience of the world that would soon become the means by which Hopper could take directive over his life, to provide a foundation for not only a new understanding of the relationship between human observer and the environment, but also for a lifelong professional career and an infamous artistic marriage.

The sketch young Hopper made of the sparrow’s skeleton, likely copied over from an anatomy textbook or off the blackboard at school, seems to pose the bird in a position of mid-flap of their wings, ready to launch, but unable because of course the bird is just, for now, bones–only a sketch.

Juliana Roth is a writer from Nyack, NY and serves as the Chief Storyteller with EHH.

This series exploring the Edward Hopper archives is a collaboration between Nyack News & Views and Edward Hopper House Museum & Study Center.