by Susan Hellauer

Earth Matters focuses on conservation, sustainability, recycling and healthy living. This weekly series is brought to you by Maria Luisa Boutique and Strawtown Studio.

Earth Matters focuses on conservation, sustainability, recycling and healthy living. This weekly series is brought to you by Maria Luisa Boutique and Strawtown Studio.If Earth Matters to you, sign up for our mailing list and get the next installment delivered right to your inbox.

It’s eyes to the sky time, as it has been for about 50 years here in Nyack. Citizen scientists, bird watchers, conservation supporters, and folks simply seeking a megadose of majestic nature flock to the top of Hook Mountain from mid September to mid November. There, they spot and count migrating raptors riding a chain of swirling updrafts to wintering grounds in South America.

The Hook is one of our region’s premier raptor migration hotspots. Hawk watches there are organized by raptor enthusiasts from local Audubon groups and the regional NorthEast Hawk Watch (NEHW). This conservation group has recorded decades of detailed data that can help researchers understand how human activity, weather and climate affect bird populations, and the rest of our natural world.

For an inside look at the why and how of the Hook Mountain Hawk Watch, Earth Matters spoke to Westchester residents Trudy Battaly and Drew Panko, both members of the NEHW Board of Directors. Panko founded the Fire Island Hawk Watch in 1982 and has coordinated it since. Battaly started coordinating the Hook Mountain Hawkwatch in 2003.

How long have you both been counting hawks?

DP: I was bird watching in the 1960s and doing some hawk watching as well. I was going up to the Hook by around 1970. It was pretty organized even back then, and on weekends we’d get 10 or 20 people at a time.

TB: I’ve been hawk watching since the late 1970s, and got very involved in counting them by the mid-1980s. So we’ve both been at it for a while. We’re not getting as many watchers now as we used to, but we have very devoted volunteers who go up there every day during the migratory season from mid-September to mid-November.

Trudy Battaly and Drew Panko are two of our region’s most knowledgeable raptor counters. Photo: Susan Hellauer

What are you seeing and counting right now?

TB: This week is when we’ll see the broad-winged hawks. They are our most numerous bird. They all come within ten days to two weeks in the middle of September. So that’s the time when most people have historically gone to watch and count hawks. It’s a true phenomenon, and a wonderful thing to experience.

What’s a broad-winged hawk, for us non-birdwatchers?

DP: Most of the hawks we know are either in the falcon, accipiter, buteo, or eagle family. The crow-sized broad-winged hawk is a buteo, along with the familiar red-tailed hawk. Buteos are generally mammal hunters and inhabit woodlands.

Broad-winged hawk. Photo: Steve Sachs Photography

When, exactly, is hawk-counting season?

TB: It starts in September, and we’re right in the middle of a pretty good week now, with several people coming up, especially this coming weekend. And we’ll still be getting some broad-winged activity into October. Organized hawk watches go until the week before Thanksgiving. The sharp-shinned hawks, which are the smallest of the accipiter family, keep coming through most of the season, into the beginning of November. From mid-October to mid-November we get the larger migrating birds—buteos like the red-tailed and red-shouldered hawks, and golden eagles and goshawks. These larger birds are easier to see.

Where are the migrating birds coming from?

DP: The broad-winged hawks are widely distributed in every woodland in North America, and we get them from New England and Canada. They congregate into very large groups during migration following thermals, which are columns of air that circle and rise on days when there’s not a strong wind. So you can see them easily, because of the large numbers flying together. That’s what makes it quite an attraction.

They’re social in migration, yet when they are nesting they are not colonial at all, and don’t nest near other broad-wings. They spread out across the woodlands, and that’s probably because they need a larger area to find enough food.

And where are they going?

TB: They drift from thermal to thermal, headed down to Central and South America, where birds arrive from all over the whole North American continent. It’s been going on for eons. What makes it so special up on the Hook is that you climb the mountain, and it’s almost like you are in their world. It’s a way to bond with nature, in a sense. It always makes me feel like there’s something right with the world, despite the bad things that have been going on. We don’t have as many hawks as we used to, but we still see some, so that means we haven’t destroyed everything yet.

On the watch for the broad-winged hawk on the Hook last weekend. Photo: Trudy Battaly

Why do you need more people up on the Hook to count the hawks?

TB: The hawks are not always easy to see, even the larger buteos, which are not quite as large as eagles. And they can get way up there, especially in the middle of the day when the thermals really rise high. Having more people helps us to spot them.

DP: We also need more physically fit people joining us because climbing the mountain is not such an easy thing to do, with knee problems and the like as we get older. So we tend to lose some of the people who’ve been watching for years, and we always need new people to start coming back and helping us out.

How do you share the information you collect about migrating hawks? This is citizen science, right?

TB: Right. NorthEast Hawk Watch is a chapter of the Hawk Migration Association of North America (HMANA). We have always submitted our data to them. Now everything’s become digitized, and the technology has really facilitated data submission. Just go to hawkcount.org to see how many different hawk watches there are all over the U.S., Canada, and Mexico. A phenomenal amount of information comes in daily at this time of the year. And NEHW uses that data to create our own annual reports.

Valley Cottage resident Felicia Napier (left), is official tally-taker on a warm September Sunday. Deb and Shawn Frederick of Nyack make the Hook hawk watch pilgrimage every year. Photo: Susan Hellauer

And what does the collected data tell you? Does it help you see how changes in climate, weather, and human activity affect hawk migration?

TB: We do have evidence that temperatures are increasing, and our regional hawk numbers are declining, generally speaking. Does one cause the other? We can’t really say that now, but it seems like there is some sort of association.

In terms of weather, bird and hawk watchers have for years been observing and associating certain wind and weather patterns with patterns in migratory flight. There are graphs showing these local weather associations on the Hook Mountain web pages. The NEHW annual reports, however, use data from the whole Northeast region, from northern New Jersey up to New Brunswick, Canada. Once you have that large a group, and want to think in terms of overall weather patterns, it makes a lot more sense to look at things like global warming.

DP: And we also know that, in most species, the first birds to migrate are the immature birds, just off the nest. So our count is also a way to measure the success of the nesting season, and whether the young were carried through the summer with enough food.

The red-tailed hawk, a familiar sight in Rockland County. Photo: Steve Sachs Photography

It sounds like every year of accumulated data can really help tell a story about our environment, and where it’s headed.

TB: Yes, that’s why all the data that everyone’s ever collected, even on a day when we’ve only counted a couple of birds, becomes very meaningful when you can look at it cumulatively. And it means that somebody who sat up on top of the Hook one day back in 1985 and counted birds is as important to the overall picture as we were when we went up there last Thursday. It’s the continuum of the volunteer effort that matters, and it’s incredible that people continue to volunteer their time to do this.

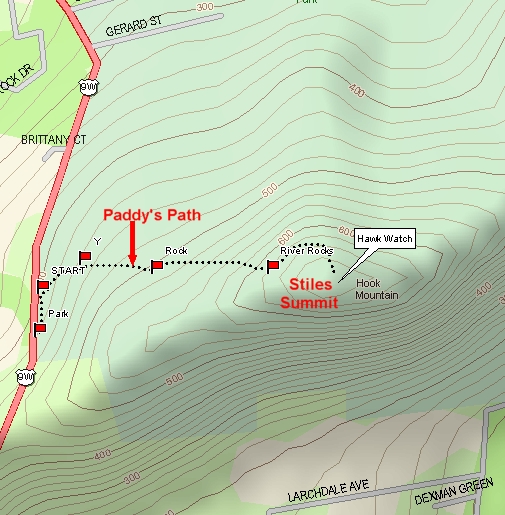

For those who haven’t yet made the 689-foot Hook ascent, the trail most taken is marked with a yellow blaze, and can be accessed from Route 9W, just south of Rockland Lake (see map and directions). There are some steep portions, but you don’t need to use your hands to climb. It’s about a 15-20 minute walk.

Less steep, but somewhat longer trails take off from Rockland Lake State Park. The one from Landing Road runs along the clifftop. Another starts near the flagpole at the Executive Golf Course. Follow the yellow blazed trail, and make a right onto the blue trail, which leads to the summit.

Volunteer tally-takers will be on the Hook every day until the week before Thanksgiving (but not when there’s snow, lightning, steady rain, or very cold temps). The more eyes, the better to spot the high-flying birds. Wear sturdy shoes and sunscreen, and bring binoculars and water. Your help—even for just a couple of hours—is needed and most welcome.

The most-used trail to the Hook summit, off Route 9W

Learn more:

- Hook Mountain Hawk Watch website

- NorthEast Hawk Watch website

- Hook Mountain Hawk Count Summary for September 16, 2018

- NorthEast Hawk Watch 2016 Hawk Migration Report (latest year available online):

- Hawk Migration Association of North America (HMANA) website: www.hawkcount.org

- “Spring Is Coming Earlier to Wildlife Refuges, and Bird Migrations Need to Catch Up” ( 9/17/18, Inside Climate News)

Adult bald eagle. “This species is increasing in numbers,” said Trudy Battaly. “It seems to have recovered from the DDT era.” Photo: Trudy Battaly

Email Earth Matters

Read Earth Matters every Wednesday on Nyack News And Views, or sign up for the Earth Matters mailing list.

Earth Matters, a weekly feature that focuses on conservation, sustainability, recycling and healthy living, is sponsored by Maria Luisa Boutique, Dying to Bloom, and Strawtown Studio.