by Barrie Peterson

by Barrie Peterson

It lay there like an unexploded hand grenade; one of the faded sheets of family history my mother had passed on: a startling document behind the charming pictures in the albums. In the 1818 will of William McCauley, my 5th great grandfather, a list of who gets his various properties: mills, dwelling house, land, distillery, and, to my shock and dismay…11 named slaves.

It took a few years for me to grapple with this. My mother’s good and gentle death in 2016 led to an inheritance and this triggered more questions: to what extent was I a beneficiary of not only white male privilege from my Calvinist Scotch-Irish ancestry, but of the unpaid toil and skills of slaves helping the maternal side of my family to prosper?

I began with ancestry.com, building a family tree with 176 individuals which led me to a two week research trip to the south. William is the preferred family name, after William of Orange, the Protestant hero landing in Carrickfergus, Northern Ireland in 1690 to conquer the Catholic Irish and seize the English crown. The McCauleys were in one of the waves enticed (or driven from nearby Scotland) by the British. But to William and his brother Matthew’s credit, they rebelled against being part of London’s “plantation” scheme and escaped to North Carolina in the mid-18th century.

I kept searching for redeeming information about this slaveholder and found some. He was a Revolutionary War period civic leader and, most impressively, a founder of the first American public university on his farm in Chapel Hill. The brothers gave land and money in 1792. I shivered and choked up at the University of North Carolina Archives as I held the Masonic apron William wore at the 1793 cornerstone laying ceremony.

Masonic apron William wore at the 1793 cornerstone laying ceremony of the Old East building at UNC

Old East, the building that Peterson’s ancestor literally and figuratively laid the cornerstone.

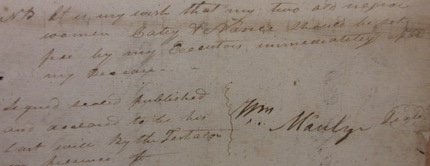

What were his attitudes toward slavery? I found a hopeful detail at the bottom of his will, “It is my desire to set free my old Negro women Caty and Nancy immediately upon my death.” Great, I told myself, at least he had a conscience.

But freeing a slave was illegal in North Carolina without a Petition to the State Legislature. I found no such action after his death in 1825 to implement his wishes by his three heirs, his sons. Maybe the two had died, yet the 1820 census lists two female slaves over 45. How else might the two have found freedom? Digging further, I found that my 5th great grandfather was a member of the local chapter of the American Colonization Society, founded by a fellow Presbyterian in Washington DC in 1816 with 11 chapters in North Carolina by 1829, but couldn’t learn if he’d been able to include any of his former slaves in the 13,000 repatriated to Sierra Leone or Liberia. There were 1200 repatriations from North Carolina, 400 from 1820-1837 to Liberia. I was also not able to ascertain if a new life in Liberia was ultimately beneficial to the men and women who were repatriated there.\

In 1808 Congress ended importation of slaves and slaveholders were panicked and many turned to breeding (rape) to increase their wealth and gain more workers for the expanding cotton and tobacco industries.

The 1820 Census also lists in his household two free colored males under 14…What did this mean? His first wife Catherine Johnston had died in 1800. McCauley married Sarah Bradford in 1811. Could he have sired the two boys whilst in between marriages; sons which he wanted to be free or treated differently (like Jefferson was doing at the time in neighboring Virginia with his and Sally Hemmings’ 7 children?).

Sally Hemmings and Thomas Jefferson

Did they “pass”? The timing suggests if they were his, this could have been a factor in him joining the ACS. He told the census taker in 1820 they were free…and does not mention them in his will. He may have been influenced by Quakers and Presbyterians who had founded Manumission societies in 1816 in counties just 30 miles west of Chapel Hill. A search of newspaper notices for reward for returning runaway slaves gave no clues of any of the eleven slaves in his will. Had any accepted British General Cornwallis 1781 offer of freedom if they joined the army occupying then? Did anyone go north to Canada on the Underground Railroad? I’m searching for the 1830 Census for his widow…and her will.

There is no gravestone for him, quite puzzling for such a prominent person in an established community and church. Brother Matthew is in a family plot between the University of North Carolina campus and the river where he owned mills and land. Was William shunned from having two sons with a slave woman and trying to get them back to Africa? I have committed to the Historian of his New Hope Presbyterian Church to support a gravestone for him once a place is confirmed.

Then there was Jacob, a “boy” given to William’s daughter Jane. Bingo! I found him and wife in the 1870 census, the first when names of people were all listed. They’d been married in 1842, documented by the Freedman’s Bureau before the Republicans sold out Reconstruction in 1877, had two children and were farmers living near other McCauleys. He is listed as white, she mulatto. Was William McCauley his father?

The 1860 Census records McCauley’s 57 slaves by gender and age, not name.

Revolutionary War officers received bonuses in the form of land grants in Tennessee (being stolen from the Native Americans, led by Andrew Jackson, our current President’s hero) so some McCauleys went to the Dickson, Tennessee area. My Great Grandfather W.L. was born there in 1868. His father George Dallas and Uncle William Hudson were Confederate officers, the latter having the local Sons of the Confederate Veterans Camp 260 clubhouse named after him. It is, ironically, in a former Presbyterian church just down the valley from a community founded by recently freed slaves called “Freedom.”

Confederate Captain in 11th TN Regiment

I visited the earnest members of the Sons of the Confederate Veterans Camp. “Heritage Not Hate” is their slogan. The leaders showed me William Hudson’s grave and the store he owned on the courthouse square. The author of the book on his unit has his jacket. I intend to join the group to participate in the discussions of taking down or properly interpreting Confederate monuments.

Another McCauley, in nearby Clarksville, a big tobacco area by the 1860 Census, owned 57 slaves. George Johnston was also a Confederate Sons of America volunteer as were two sons who quickly were killed. Here my research hit an exciting point when I found the 1864 enlistment sheets for the Co. H 15th United States Colored Regiment. After the Emancipation Proclamation, Pfc. Allen McCauley escaped to the Union lines and fought for freedom. A week after he was mustered out in 1866 a Memphis city official incited a white mob which in a week killed 57 Blacks, burned dozens of houses, churches and school. This before the local slave trader and Confederate general Nathan Bedford Forrest started the Klu Klux Klan to begin American domestic terrorism in earnest.

One hundred and seventy five colored regiments with 178,000 men fought in the civil war

Allen and his white wife, a mill owner’s daughter and children show up in the 1870 Census and I am working to bring that line of the family up to the present and reach out to communicate. The McCauleys I’ve traced so far enslaved 229 people, only half known by name.

I plan to encourage the University of North Carolina to review its past reliance on slavery and, as has Brown and Georgetown Universities have done, rewrite its history and make scholarships available for descendants of people who were enslaved to the institution’s benefit. I hope to provide as much information as I can about the slaves whose labor benefitted my family.

Valley Cottage resident Barrie Peterson is active in local cultural, philanthropic and and religious activities. He is retired from teaching Business Ethics and working in social services and public policy.

Valley Cottage resident Barrie Peterson is active in local cultural, philanthropic and and religious activities. He is retired from teaching Business Ethics and working in social services and public policy.

Words & Images is a column that features the work of students from , Writing Your Truth. This weekly feature is sponsored by River River Writers Circle, which invites you to join writers and scientists in the forest of the central highlands of Vietnam for writing workshops, presentations, and explorations toward transformative ecological thought in January, 2019. Program applications are due by July 31, 2018.