by Mike Hays

It’s the middle of the 19th century and a lone fugitive slave has missed his “safe house” while traveling through Nyack on his way north. He’s tired. And he’s frightened and for good reason: most of Nyack supports the Fugitive Slave Act. If captured, he will be returned to enslavement again in the South. As the sky starts to brighten, he sees towering Hook Mountain to the north and recognizes that he’s standing in a vineyard that slopes down to the Hudson River. Fortunately, the owner of the Upper Nyack farm is abolitionist George Green, son of John Green, the builder of the oldest remaining house in Nyack. Green discovers the fleeing man in the morning light and guides him to a nearby place of safety.

The story of George Green helping a fugitive slave is one of only two documented accounts of local citizens helping runaway slaves (see The History of Rockland County.). The details of how the Underground Railroad worked in Nyack — or whether it existed at all — are a matter of debate. Even the name, the “Underground Railroad,” suggests a more organized system than probably existed. However, there is often truth in rumors, and it has long been said that Nyack was a “station” and Cynthia Hesdra was a “conductor.”

The story of George Green helping a fugitive slave is one of only two documented accounts of local citizens helping runaway slaves (see The History of Rockland County.). The details of how the Underground Railroad worked in Nyack — or whether it existed at all — are a matter of debate. Even the name, the “Underground Railroad,” suggests a more organized system than probably existed. However, there is often truth in rumors, and it has long been said that Nyack was a “station” and Cynthia Hesdra was a “conductor.”

The Underground Railroad according to Henry Louis Gates Jr.

Henry Louis Gates Jr, a noted African American History professor from Harvard, debunks many of the myths about the Underground Railroad in Who Really Ran The Underground Railroad? He writes that the number of escaped slaves was relatively few compared to the total slave population (perhaps 50,000 escapees versus a total enslaved population of 3.9 million). Escapees were predominately young men (Harriet Tubman not withstanding) who had no other family connection. Most came from the mid-Atlantic slave states, arriving in New York and Philadelphia by rail (including Frederick Douglass), boat, carriage, and foot.

While the popular myth of the Underground Railroad includes many white “conductors,” Gates cites Yale professor David Blight in debunking this myth. “Much of what we call the Underground Railroad, was actually operated clandestinely by African Americans themselves through urban vigilance committees and rescue squads that were often led by free blacks.”

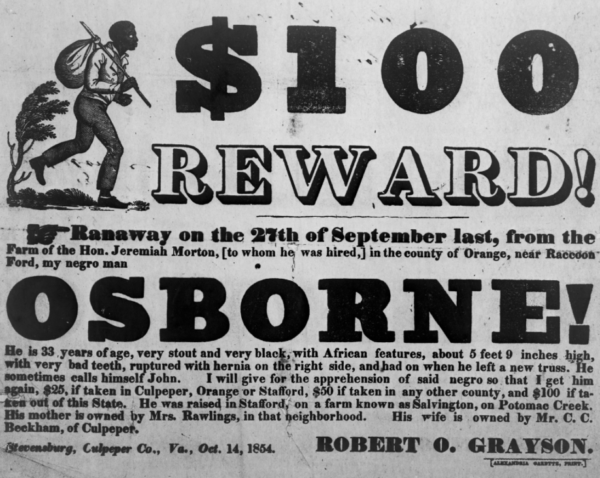

These type of reward ads appeared regularly in newspapers. Notice that the bounty goes up the further away the fugitive is found. Note also that his mother and wife had different owners.

Escaping was not a movie. It was dangerous and difficult. Few made it. There were no sanctuary cities under the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850. Local officials were required to arrest fugitives. Successful officials were given promotions and bonuses. Slaves that were caught had no recourse to trial. Anyone caught helping a fugitive was subject to six months imprisonment and a fine of $1,000.

Slavery in Rockland County

Tom Lewis’s The Hudson: A History shows that slavery in the Hudson Valley had many similarities to slavery in the deep south. Although less prevalent on the smaller farms in Rockland County, slaves were used to work large farms and estates especially on the eastern shore of the Hudson River. However, in 1790, most of the Rockland’s wealthiest families owned slaves. One family owned 11. Peter and Tunis DePew, from the family of wealthy Nyack landowners, together purchased five slaves in 1806. Of 224 residents of African descent in Rockland in 1790, only 26 were free.

Slavery was outlawed in New York rather late, in 1827. Even then, and until 1841, slaveholders from other states were allowed to bring their slaves into New York.

Cynthia Hesdra (1808-1879)

In Nyack, Cynthia Hesdra appears to have been the key local “conductor.” Hesdra grew up free in an African American Piermont community called Mine Hole. At some point she became enslaved in the south. Edward D. Hesdra, self-described as a free Hebrew mulatto, purchased her freedom and they married.

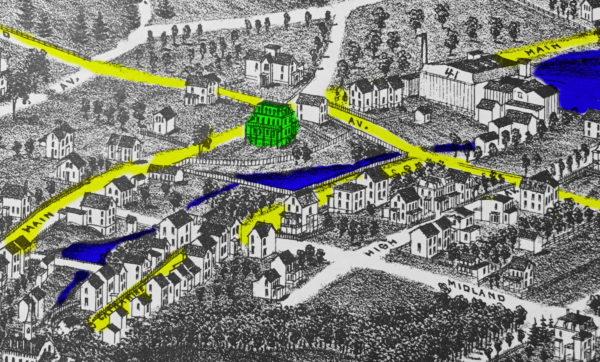

The large Hesdra house is highlighted in green on the 1884 Burleigh map of Nyack. The house is near the corner of Main Street (in yellow) and Hillside Avenue (or 9W). The Nyack Brook (in blue) runs just behind the house between Main Street and Catherine Street. The brook flows down from the ice pond on the right to the Nyack Reservoir (just below the house in this graphic), which abuts the Hesdra property. An historical marker has been placed on this corner.

The Hesdras moved to New York City where Cynthia owned and operated a successful laundry while Edward ran a furniture store. Cynthia was an early New York City black landowner near Minetta Lane in Manhattan, later known as “Little Africa.” Nearby was the meeting place of the New York Vigilance Committee, run by African Americans. The group fought for freedom for escapees in the courts and provided the means to travel further north to New England and Canada.

When did the Hesdras move to Nyack? In 1859, Cynthia Hesdra’s name first appears on Nyack maps as a landowner. Subsequent maps in 1872 show Hesdra as the owner of several buildings and properties in Nyack. These include a large house at 294 Main Street just off of Highland Avenue (9W) described as a large four-story house with a second-floor balcony which wrapped 3/4 of the way around it.

Cynthia Hesdra was a wealthy woman. Her contested will was the subject of a famous New York State court case explored in Dr. Lori Martin’s book, The Battle Over The Ex-Slave’s Fortune.

The Nyack Brook ran through the backside of Cynthia’s property on the corner, along with a spring-fed reservoir for the town water company. Local free African Americans lived in a second house closer to Highland Avenue on the property and also in nearby Catherine Street, which was known as African Lane in the early 1800s. So it makes sense that fugitives could have found this location a reliable refuge. The Hesdra houses no longer exist and an onsite historical marker makes note of the fact that it is believed that this was the site of a station on the Underground Railroad. However, some local historians dispute this notion, noting that the deed to the Highland Avenue property was dated after the Civil War.

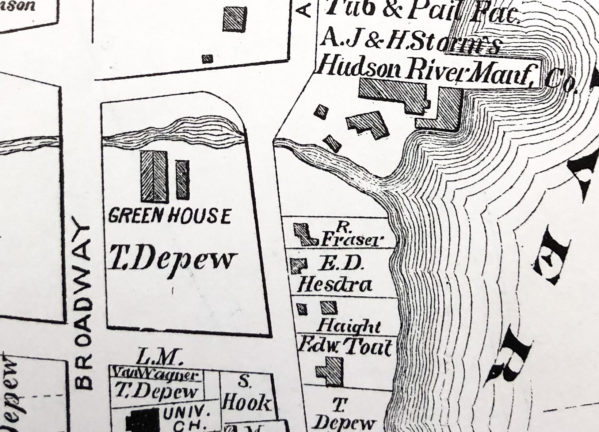

Hesdra property on the Nyack riverfront in this 1876 map. The property is on Piermont Avenue near where the Nyack Brook enters the Hudson River. Memorial Park is now located just above the river on this map. It is interesting to note that deeds at the time were in the name of the male of a family. Thus. E.D. (or Edward) Hesdra is on the property despite the fact that Cynthia was the family “moneymaker.”

Hesdra also owned property on Piermont Avenue near the mouth of the Nyack Brook across from Tunis DePew’s greenhouses. This location is an even better potential choice for a “station;” it is near a key north/south road, near the Nyack Brook and the Hudson River.

Cynthia Hesdra is the one name that appears in every historical account of the Underground Railroad in Nyack. Because of her wealth, business acumen, relationships in New York City, and her properties near key locations on water and land routes north, it seems probable that she was the key figure helping fugitives escape further north.

Was Nyack Brook a landmark for the Underground Railroad?

Historians say fugitives used geographical features to guide them north.

Jacqueline Tobin and Raymond Dobard book, Hidden in Plain View, introduced the notion that “freedom” quilts embedded with geographical features were created as a secret “map” to provide route codes for fugitives who mostly did not read. Could Nyack Brook have been in the quilt code for fugitives going from Jersey City to Newburgh? Was the brook a signpost on the mental maps passed to runaways? How did runaways find their way in a hostile landscape? Consider the following:

- Giles R. Wright argues that quilts coded with maps are a figment of white historians’ imagination. Henry Louis Gates, Jr. agrees, saying that quilt code maps are a myth.

- Nyack Brook is not a significant waterway, certainly not when one considers the numerous waterways west of the Palisades between Nyack and Jersey City. Even someone who knew their way might have trouble finding the brook in the dark, let alone someone unfamiliar with the area.

- Can you imagine walking from Jersey City to Nyack — in one night? And then walking from Nyack to Newburgh, the next night? The distance is too long for a single night trip. There had to have been other stops or some other form of transportation. Travel by wagon is possible, assuming a trustworthy partner.

The view of the river and Nyack Memorial Park from the Bench By The Road in honoring Cynthia Hesdra. The Nyack Brook enters the Hudson River just at the right of the photo.

- It is easy to imagine fugitives traveling up the Hudson River and landing at the entrance to Nyack Brook and then heading to the nearby Hesdra house or to another shelter of her choice.

- Likewise, it is possible that the Hudson River would have provided a convenient and relatively safe way to get to the next known stop in Newburgh, given the large amount of river traffic. Free people worked on boats and the docks of New York City and were known to aid escapees. It is very easy to imagine someone from New York ferrying an escapee to or from Nyack. All it would take is a willing local mariner.

- Hesdra had numerous business connections in New York City, where she owned land. As a free businesswoman she was undoubtedly a contributor to the New York Vigilance committee and was more than a little aware of what was being done to help fugitives. With such connections it is indeed possible that she was able to work with a trustworthy partner to use land or water transport. Maybe the Underground Railroad was a waterway to Nyack?

- It is likely that Nyack was a stop because of the location of a community of African descent, the presence of a wealthy benefactor, and, possibly, I would argue, the relative security of traveling by river.

Because Cynthia Hesdra lived next to the Nyack Brook, and because it is likely that fugitives stayed with her or in the nearby community on their way north, over time it is possible that in the popular imagination that the Nyack Brook became associated with the Underground Railroad. It is pleasing to think of our little brook was a key Underground Railroad marker, but really this obscures the heroes who should be honored for standing up for equal rights when it was very difficult to do so.

Sources

- The Battle over the Ex-Slave’s Fortune: The Story of Cynthia D. Hesdra, Lori L. Martin

- Gateway to Freedom: The Hidden History of the Underground Railroad, Eric Foner

- The History of Rockland County, Frank Green

- Who Really Ran the Underground Railroad, Henry Louis Gates Jr.

- Nyack In Black & White, Carl Nordstrom

- The Hudson: A History, Tom Lewis

- Nyack Sketch Log: The Underground Railroad, Bill Batson

- Nyack Sketch Log: Tony Morrison’s Bench by the Road, Bill Batson

- Nyack Sketch Log: The Historic Towt House, Bill Batson

Photos by Mike Hays

Michael Hays is a 30-year resident of the Nyacks. He grew up the son of a professor and nurse in Champaign, Illinois. He has recently retired from a long career in educational publishing with Prentice-Hall and McGraw-Hill. He is an avid cyclist, amateur historian and photographer, gardener, and dog walker. He has enjoyed more years than he cares to count with his beautiful companion, Bernie Richey. You can follow him on Instagram as UpperNyackMike.

Nyack People & Places, a weekly series that features photos and profiles of citizens and scenes near Nyack, NY, is brought to you by HRHCare and Weld Realty.

Nyack People & Places, a weekly series that features photos and profiles of citizens and scenes near Nyack, NY, is brought to you by HRHCare and Weld Realty.