Earth Matters focuses on conservation, sustainability, recycling and healthy living. This weekly series is brought to you by Maria Luisa Boutique and Strawtown Studio.

Earth Matters focuses on conservation, sustainability, recycling and healthy living. This weekly series is brought to you by Maria Luisa Boutique and Strawtown Studio.If Earth Matters to you, sign up for our mailing list and get the next installment delivered right to your inbox.by Susan Hellauer

by Susan Hellauer

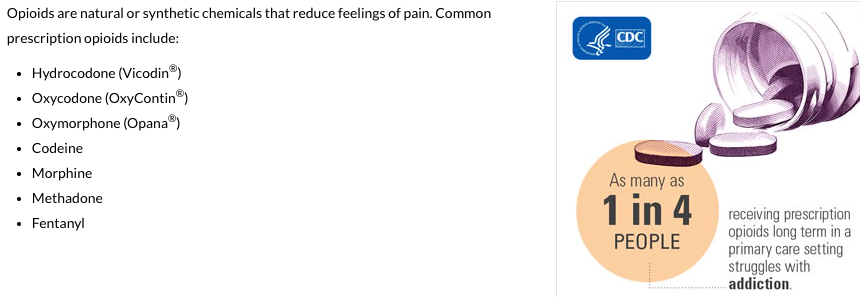

America’s opioid addiction epidemic has been claiming about 100 lives a day, one of them in my own family. It nearly killed another, and forever changed us all. In our case, these addictions began with post-orthopedic and dental surgery prescriptions handed directly to young people.

It’s on my mind every day. And it was especially so as my own back surgery loomed at Nyack Hospital last week. In light of our national addiction agony, I assumed that post-surgical pain control with opioids would be a subject of close oversight. The reality? It was anything but.

A little pain

The microsurgery went well, and erased the brutal sciatic nerve pain that had dogged me for months. I woke up in recovery, and was rolled up to the clean, bright private room I’d lucked into. My caregivers were attentive, skilled and compassionate.

The small lower-back incisions were sore, and so was my throat—the result of surgical intubation. But, minus that screaming sciatica, my pain was minimal and life was good again. “Please, no narcotics,” I squawked. Just some over-the-counter pain meds and a cup of hot tea would do. Nevertheless, two heavy-duty opioid pills arrived, and were sent away.

The next morning, I flipped through my discharge instructions, which included a four-page patient education handout (dated 2007) about pain management. It stressed the importance of alleviating post-surgical pain with opioid medications, among other techniques. Post-surgical pain control is indeed important. But did the pamphlet educate patients on the warning signs of addiction? There was this, and only this:

What about addiction?

If you have to take pain medicine for a long time, this does not mean you are an “addict.” You are following your doctor’s advice and getting a treatment you need.

I told my discharge nurse that, with my pain scale level at “1” or “2” at most, no narcotic prescription was wanted or needed. A call to my pharmacy later in the day revealed that there was an opioid scrip there, waiting for me.

If you see something . . .

Even without my own family’s loss, the daily American opioid body count of 100 and growing—soon up to 93,000 a year according to one projection—means that Silence = Death, to borrow a grim slogan from the AIDS epidemic.

With the good fortune to write a weekly column, I was able to send my story and the pain management handout to Nyack Hospital’s media office. I requested interviews with the directors responsible for patient education and opioid prescription oversight.

Would they give me the brush off, or the bureaucratic stiff arm? What I got was not what I expected.

Pain, Incorporated

Thanks to deep investigative reporting in recent years, the origins of this opioid crisis are no mystery.

The sharp rise in opioid prescriptions since the mid 1990s was engineered largely by Connecticut drug manufacturer Purdue Pharma, a family firm with a diabolical knack for medical marketing. And Purdue has made its owners—the Sackler family—wildly rich. Patrick Radden Keith’s recent landmark article in the New Yorker details the Sacklers’s rise, from the aggressive marketing of the tranquilizers Librium and Valium in the 1960s (pushed even for vague, psychosomatic complaints), to the 1996 launch and marketing of Oxycontin—a timed-release form of the powerful generic opioid oxycodone. To date, the deceptive marketing of their “virtually non-addictive” Oxycontin has brought thousands of public and private lawsuits down on Purdue, which they invariably settle out of court, often for millions of dollars—mere drops in their overflowing opioid-profit bucket.

And Purdue didn’t just market Oxycontin to individual physicians. Radden’s report points to a Jacob’s ladder of Purdue-paid doctors and federal agency officials in the late 1990s, building support (along with some legitimate studies) for a new medical standard of intensive opioid-based post-surgical pain management. The result? That now-familiar pain scale of 1 to10, part of a standard of greatly-increased opioid use for “better healing” established in 2001 by the Joint Commission, which accredits U.S. healthcare organizations.

As Oxycontin’s 2013 patent expiration drew near, Purdue came up with a new formulation in order to extend their ownership of the profitable scrip. This change in 2010 would deter the drug’s rampant abuse by addicts, who could now no longer crush and snort or inject it, concentrating a 12-hour dose into one monster high. Sniffing out a lucrative opportunity, Mexican heroin cartels rushed in to fill the void and drop the price of addiction, often by using cheaper synthetic drugs, like highly-concentrated and often deadly fentanyl. (The number of heroin deaths in the U.S. spiked by over 20% from 2014, to 13,000 in 2015.)

The opioid crisis: recovery speaks

A recent study of 36,000 surgery patients bears out what recovery specialists are hearing from their patients. According to the study’s author, “pain medication [prescriptions] written for surgery are a major cause of new chronic opioid use for millions of Americans each year.”

Instead of fending off my questions about opioids and surgery-patient education, Nyack Hospital met my challenge and immediately set up an interview with Marcey Davis, interim program director for the Behavioral Health Department. She oversees the Recovery Center, under the Behavioral Health umbrella.

Davis said that her department does not keep statistics on root causes of addiction yet, but when it comes to addictions that begin with prescribed pain medication, “it hasn’t always been reported, but we are hearing it more and more. Not everyone is prone to addiction, but there are those who are more prone than others. Some patients can take [opioids] and not be addicted at all, but it’s also a fact that some patients have a very low tolerance for pain, and they tend to overuse pain killers.”

So, with so many moving parts, how can a hospital treat patients’ pain adequately while also keeping addiction at bay?

“It really does ‘take a village,’” said Davis. “We’re all in this together. The treatment team should be educating the patient. The patient should be letting us know their health history.” Davis notes that this goes beyond opioid use, to alcohol and other pain-relieving products. “I think in a perfect world we will become better at our prescribing, better at addressing the pain, better at understanding the levels of pain, and what other options are available. This is getting a lot of attention now, so I hope we don’t lose any momentum, and just continue to make our systems and processes better. We’ve started, but we’re not quite there yet.”

An opioid crisis “game changer”

It turns out that Nyack Hospital—and all American hospitals—are about to make a major course correction.

Robyn Postighone (RN, MPA) is Nyack Hospital’s Director of Quality and Infection Prevention. She works with all hospital departments to insure that they are adhering to the accreditation standards of the Joint Commission, which, she told me, will roll out a new national standard for pain management in January 2018. “Their expectation is that a hospital will develop a pain committee to look closely at the use of opioids: what we are dispensing in-house, and what our physicians and other licensed independent practitioners are prescribing as part of the discharge plan of care.”

The Joint Commission used to advocate that patients be better medicated, Postighone said. “The sentiment was that hospitals weren’t adequately providing pain medication to our post-operative patients—that they were not able to heal as quickly, not able to get out of bed or walk as soon as they should have, because they weren’t able to get relief from pain. But the Joint Commission has asked us to shift our focus. They are now asking us to minimize the use of opioids. They are saying: ‘What can you do other than prescribing pain medication?’ There are a lot of different methods of pain relief that they are now encouraging hospitals to facilitate.”

Nyack’s Chief of Anesthesia, Dr. Roger Raichelson, is already involved in the new initiative through hospital’s orthopedic program, looking at replacing opioids with non-addictive alternatives. “He and his group are taking an active role, working with us on ways to do things differently for post-operative patients,” said Postighone. “Everyone has been supportive of changing our habits of prescribing strong narcotics and opioids to patients.”

New, comprehensive education materials for patients are in the works, and the pain committee is now being formed. Postighone asked if I would sit in with them when they meet in January, as a voice from the other side.

“I’m in,” I told her.

Learn more:

- “Who Is Responsible for the Pain-Pill Epidemic?” by Celine Gounder (The New Yorker, 11/8/13)

- “How the American Opiate Epidemic Was Started by One Pharmaceutical Company,” by Mike Mariani (Pacific Standard, 3/4/15)

- “STAT forecast: Opioids could kill nearly 500,000 Americans in the next decade,” by Max Blau (STAT Health News, 6/27/17)

- “Oversupply of Pain Pills After Surgery Helps Fuel Opioid Epidemic,” by Ronnie Cohen (Reuters, 8/2/17)

- “The Game Changer for the Opioid Epidemic” (Dorn Innovative Health Solutions, 10/4/17)

- “The Family That Built an Empire of Pain,” by Patrick Radden Keefe (The New Yorker, 10/30/17)

- U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Opioid Overdose

- “Questioning A Doctor’s Prescription For A Sore Knee: 90 Percocets” (NPR, 11/22/17)

- “Should Hospitals Be Punished For Post-Surgical Patients’ Opioid Addiction?” (NPR 11/26/17)

- Many doctors and their chronic pain patients are pushing back against the CDC’s new lower-dose, shorter-term prescribing guidelines for opioids: “A ‘civil war’ over painkillers rips apart the medical community — and leaves patients in fear” (STATNews, 1/17/17)

featured image from the U.S. Centers of Disease Control

Read Earth Matters every Saturday on Nyack News And Views, or sign up for the Earth Matters mailing list.

Earth Matters, a weekly feature that focuses on conservation, sustainability, recycling and healthy living, is sponsored by Maria Luisa Boutique and Strawtown Studio.