Bicycles — or an earlier version of what we now think of a bike — had a place on our streets before cars were a thing.

by Herbert C. Hallas

Statewide interest in bicycling exploded in New York State 148 years ago when newspapers began to warn readers about an impending “fearful outbreak” of “velocipede mania.” According to the January 10, 1869 issue of the New York Times, the first sight of a velocipede created “wonder and amazement among all classes” which made them “anxious to mount the fiery steed.”

Via Herbert Hallas

The velocipede was an advance over the two-wheeled vehicle known as the “hobby horse” or “draisine” which had been patented in Germany in 1818. It was propelled by the rider’s feet, walking or running. The velocipede adapted the hobby horse by adding cranks and pedals to the front wheel. The new vehicles became known as bicycles or velocipedes by enthusiasts, and boneshakers by detractors. They were heavy, weighing about 60 pounds, and difficult to mount. To brake a velocipede, a rider had to back peddle and pull a cord near the handlebars which activated a spoon brake on the back wheel.

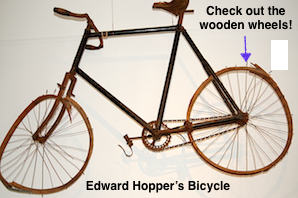

On some models, there were curved leg rests projecting out over the front wheels that a rider going downhill could use to raise his or her feet from the rapidly spinning pedals. The frame was made of wrought iron and the wheels and spokes were wood. It had iron tires. The axle bushings were made of bronze and lubricated with whale oil. The front wheel usually was about 36 inches in diameter and the rear about 20 inches.

The major velocipede manufacturers in the state were located in New York City. They included the carriage maker Calvin Witty, and the firms of Pickering and Davis and G.H. Mercer and Monad. New velocipedes were priced from $100 (about $1,700 in today’s dollars) for a plain model. However, those with ivory handles and silver plating might cost $200.

As interest in the velocipede mushroomed into a full-fledged mania, devotees organized velocipede riding academies and bicycle clubs. Sheet music for new songs such as “The Velocipede Galop,” and “The New Velocipede,” appeared in music stores.

Indoor velocipede rinks opened throughout New York State from West Troy, Saratoga and Malone in the east, to Gowanda and Buffalo in the west. In several urban centers, entrepreneurs found new uses for old buildings to meet the growing demand for smooth, safe places to ride—a freight house in Albany and an art gallery in New York City were converted into velocipede rinks.

[pullquote]Accidents involving velocipedes led to heated arguments about whether or not to ban them from public roads and sidewalks. Some newspapers described velocipedes as the “new terror of the streets.” In Troy, the press editorialized, “the streets are no place for the velocipede.”[/pullquote]

In no time, human-interest articles about races between velocipedes and horses, street cars, and pedestrians or walkists, began to appear in newspapers. Sports news soon included stories about racing competitions between velocipedists. The Boston-New York sports rivalry intensified when Walter Brown of Boston rode 50 miles in less than 6 hours in the Boston Velocipede Rink in preparation for an upcoming race against one of the Hanlon brothers from New York City for a cash prize of $1,000 (about $17,000 in today’s money). Velocipede races were also held on the horse-racing tracks at fair grounds such Dutchess County Fairgrounds in Washington and Franklin County Fairgrounds in Malone.

The bicycle belonging to American realist painter and Nyack native Edward Hopper.

At the height of the mania, public discussion about the use of velocipedes was typically light-hearted. In Malone, one user reported that after riding for a few hours, he felt as though “he had accidentally fallen into a threshing machine and had been carried up upon the thing-um-a-jig under the horse’s feet.” In New York City, readers learned that a rider increases the speed of the velocipede “by lively agitation of the driving wheel. The more revolutions you make, the faster you will go. That is why the Mexicans will be the greatest velocipedists on this continent. As the French have been in Europe.”

On a more serious note, accidents involving velocipedes led to heated arguments about whether or not to ban them from public roads and sidewalks. Some newspapers described velocipedes as the “new terror of the streets.” In Troy, the press editorialized, “the streets are no place for the velocipede.”

Toward the end of 1869, there were signs that velocipede mania was coming to an end. Only three velocipedists entered a race at the Albany fair grounds. Use of velocipede rinks in New York City had declined. In fact, some rinks had become “the resort of roughs who monopolize the floors.” Second-hand prices for velocipedes had sunk to an average of $22 (about $380 in today’s dollars).

Within a few years, the velocipede gave way to the English high-wheel vehicle known as the “ordinary” or “penny-farthing.” Introduced at the Philadelphia Centennial Exposition in 1876, it had solid rubber tires on wire-spoked wheels. Its larger front wheel, as large as the rider’s leg would allow, meant it could cover more ground with each revolution. By the 1880’s, a new craze was underway and the boneshaker had become a faded memory.

Herbert C. Hallas is the author of William Almon Wheeler: Political Star of the North Country. He publishes a blog about New York State history at www.herberthallas.com. This article was originally published at NewYorkHistoryBlog.org on 8/6/2003.

Street Beat is a weekly feature on Nyack News And Views covering streets, sidewalks, cycling, mass transit and safety. Sponsored by Velo Bistro Wine Bar, Weld Realty and Bike Nyack.