Phat Thai (Pad Thai) is a Chinese-style dish. So how did it come to symbolize Thai food?

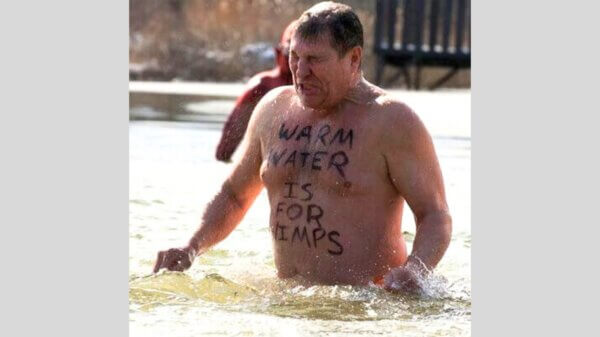

Phat Thai from a stall in Bangkok’s Ari neighborhood / Ben McCarthy

by Ben McCarthy

It’s just after 7pm in Bangkok’s Ari neighbourhood and after my 23 hour flight from New York I’m out looking for dinner. For me this means finding a street stall or open-air shopfront restaurant, sitting down and ordering what the locals are eating. In a city like Bangkok this is particularly easy; you can seldom walk 20 feet without encountering food.

I decide on a stall set up on a street corner and packed with locals. I realize they are selling Hoy Thod, a crispy fried oyster omelet, and Phat Thai, Thailand’s eponymous noodle dish, one that I tend to avoid whenever I am in Thailand. Tonight is different: there are locals eating here, not one farang (the Thai term for foreigner) besides me, and there is a plate of Phat Thai on everyone’s table. I opt for one of each. The Hoy Thod is smoky and a little crispy, not the best I have eaten but not bad either. The Phat Thai though is delicious, an entirely different dish from its Americanized cousin.

If you have eaten Thai food in the U.S., chances are you’ve eaten Phat Thai (usually spelled Pad Thai). The dish of stir fried noodles has become synonymous with Thai food worldwide and is largely viewed as Thailand’s most famous dish. Yet Phat Thai is not really Thai at all, but a mashup of Chinese-style stir fried rice noodles with traditional Thai ingredients like palm sugar, tamarind and chili. So how did this augmented version of Chinese-style noodles become the symbol of Thai food?

The answer is a long and convoluted one but begins with Luang Phibunsongkhram (commonly referred to as Phibun), Thailand’s authoritative Prime Minister from 1938-1944. “Luang Phibunsongkhram,” according to historian David K. Wyatt, “is one of only a handful of people who definitevley put their stamp on Thai history.” During his six years as Prime Minister, Phibun enacted a series of mandates that modernized and westernized Thailand forever. The 12 Mandates, as they were called, were meant to civilize Thailand and show the rest of the world, including colonizers such as the British and French, that Thailand was firmly in charge of its own destiny. These mandates included changing the name of the country from Siam to Thailand, making Thai the national language, abolishing the formal use of hill-tribe languages as well as Laotian (in the Northeast) and Chinese; he also mandated nationalistic practices such as saluting the flag, learning the national anthem and wearing Western styles of dress.

Phat Thai from a stall in Bangkok’s Chinatown, this version wrapped in egg / Ben McCarthy

And then there was the creation of a national dish, one that both developed “Thai-ness” and“demonstrated the strength and unity of the Thai nation.” The late 1930s were a particularly low period for Thailand economically and the Phibun government wanted a dish that was simple to prepare and healthy to eat. Rice noodles were cheap and the addition of bean sprouts, egg, and tofu made the dish rich in inexpensive proteins.

While the Phibun government insisted that its primary goal was uniting the nation and promoting “Thai-ness,” many of the Prime Minister’s policies were directly discriminatory to the large ethnic Chinese population living and working in Thailand. Discrimination against Chinese and other ethnic minorities was often rebranded as nationalism.

“During the first nine months of Phibun’s government, a comprehensive series of anti-Chinese (or as the government put it, pro Thai) enactments were put into effect,” according to Wyatt. These included making certain occupations forbidden to foreigners, increasing taxes on the Chinese commercial class, inspecting Chinese schools to insure that Chinese was not used for more than two hours a week and closing down all but one of Thailand’s Chinese newspapers.

The invention of Phat Thai then, a Chinese style stir fry of rice noodles, may have been an attempt to create a unifying national dish, while whitewashing over the Chinese culinary influence and customs that were common throughout Thailand. After all, the full name of the dish in Thai is Kway Teow Phat Thai, kway teow means rice noodles in Chinese.

The influence the Chinese had on many aspects of Thai society should not be overlooked. Even before the Siamese capital was moved from Ayutthaya to Bangkok in 1774 (after being ransacked by Burmese invaders), Chinese immigrants played a pivotal role in society, making up a majority of the merchant class and dominating certain industries such as pork and tobacco farming.

Much of the population eventually adopted Chinese customs, including culinary ones, and Chinese immigrants brought many dishes that are considered quintessential to Thai cuisine, including stir-fried rice noodles, to Thailand. Today, 14% of the Thai population is Chinese, and Thailand is still home to the largest Chinese community outside of China.

Wander the streets of Bangkok during the dinner hour and you will see enumerable street food stalls and little shop front restaurants where every dish imaginable is being prepared. But no matter where you are in the city there will always be one stall selling Phat Thai. The dish has become synonymous with Thai street food; whether you are in the center of the city or one of the outlying neighbourhoods a Phat Thai seller is never far away.

Ben McCarthy studied pre-med and creative writing at Hunter College. He is the lead guitarist in the alternative rock band Regret the Hour.