In the opening years of the 20th century but around mid point in the Modern Movement, the highly respected and influential American realist painter, Robert Henri, (1865-1929), instructed Edward Hopper and other students to be present in their paintings. He told them not to paint what they saw, but to paint how they felt about what they saw.

A little more than a decade later, Walker Evans read Gustave Flaubert’s (1821-1880), Working Philosophy. It’s primary assertion took hold: “Like God in Creation, he should be everywhere felt, but nowhere seen.”

These two struggling, self-conscious artists are now giants, icons in the world of art. Their pioneering spirits championed the common place and the every-man. Their work forms the foundation of the genre, American Scene, aka, Regionalism in art and photography.

Robert Henri and the Ashcan School Artists started the tradition of American Realism, around 1908, recording street life and social scenes, taking notice of the vitality and plight of the working class. Then in 1910, metaphysical art took hold, reminiscent of the 1750’s Romantic period that had swept the world – embracing spirituality, nature and individual consciousness over intellectual reason, industry and progress – from art for art’s sake to art for life’s sake. Giorgio de Chirico’s, metaphysical period, 1910-1920, was followed by the Surrealist The Manifesto of Surrealism, declaration in 1924, and followed by Edward Hopper’s first significant painting, House by the Rail Road, in 1925. The period may have culminated with Walker Evans’s rural Alabama documentary ode to three sharecropper families in collaboration with the writer, James Agee: Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, 1936. A rebirth of self-awareness and psychological consciousness relative to the plight of the every-man, the common folk caught in the never-ending wheel of progress, politics, industrialization and war had taken hold.

Metaphysics as a branch of philosophy, attempts to explain our relationship to “that which is” the natural world. A perfect analogy came through a description of Wordsworth’s poetry: “observant, meditative and aware of the connection between living things and objects. There is the sense that past, present, and future all mix together in the human consciousness. One feels as though the poet and the landscape are in communion, each a partner in an act of creative production.”

Hopper, Evans, the Hudson River School and William Wordsworth returned time and again to particular types of places or scenes because it provided an opportunity to observe ordinary life in relation to “place,” its changing light, the objects placed or found there and the people who ventured or lived there. They sought the enduring human spirit in bucolic frontier and country settings, in vernacular architecture, in ordinary homes on ordinary streets, in cheap hotels and roadside America and in everyday objects fashioned by human hand or industry that might make life just a little bit easier, a little bit more interesting, or a little bit more salable in order to survive and endure. Walker Evans (1903-1975), was drawn to “incongruous surreal like street scenes, the poetic resonance of ordinary objects and the battered nobility.”

Since I began photographing outdoors a little over a year ago, I’ve tuned into the metaphysical dimension in nature relative to objects placed or found there. Reading about transcendence and metaphysics as reoccurring themes in art has demonstrated the collective conscious time and again reestablishes a bridge back to nature. So much history, art and writing precedes us, relative to one man’s inspiration from nature versus another man’s desire to overtake it, including the art of Edward Hopper (1882-1967), the Surrealist Art Movement (1910’s-1960’s), the Hudson River School Painters (1825-1870’s), and the Romantic Movement (1761-1850’s), which includes the poetry of William Wordsworth, (1770-1850).

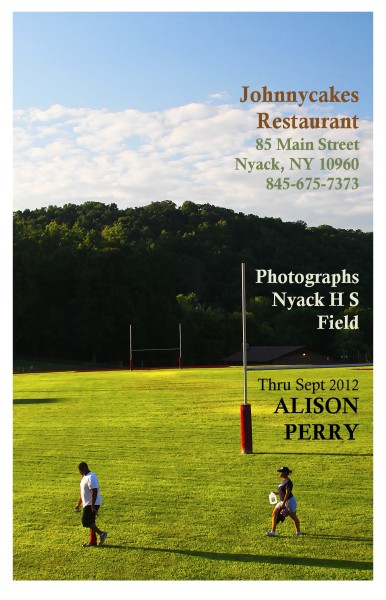

Photographing Americana and iconic objects and also the newer and older Nyack High Schools, the upper and lower baseball, track and football fields, the green clover covered expanses, the receding woodlands, the raking light, the shifting clouds, tiny distant human figures in vast atmospheric landscapes in sunlight sometimes so bright, things take on a surreal look. It’s easy to see why Hopper used light for psychological effect. He was paying homage to the every-man, who not unlike himself, was seeking rejuvenation from the psychological toll of urbanization. People painted out doors, on a window sill, in a sailboat or otherwise, were basking in the warmth of the sun, the most spiritually and emotionally transforming element in nature. For me, his paintings aren’t so much about loneliness and isolation as they are about contemplation and rejuvenation of the spirit.

In the early evening, rabbits and groundhogs feed along the perimeter, the deer begin to exit the woods to graze nearby, joggers jog, walkers walk, teams meet to practice or compete, families come to spend time together and teens gather to hang or exercise with peers. Along the back perimeter a mature tree line rises to meet the lower portion of the ever present summit of Hook Mountain. A part of Nyack’s cultural identity is attached to its serenely imposing form, reminding me of the metaphysical component of the Hudson River School landscapes.

Alison Perry’s photographs will be on display at Johnnycakes Restaurant, 84 Main Street in Nyack, during the month of September.

Shot with Canon 28-135 mm F3.5 lens

Shot with Canon 28-135 mm F3.5 lens

EXP: 1/125 @ F8 ISO 400

All of which brings me back to photography. Since it’s important to unify objects in the landscape, it’s very important to pay attention to spatial relationships, to render the scale of objects proportionally to the ground and backdrop, or pictorial space. The 35mm format and the lens determine the pictorial space, making it important to choose the right focal length. Wide-angle lenses decrease the size of objects, but increase the angle of view. Telephoto lenses increase the size of objects but decrease the angle of view and medium distance lenses come closer to what the human eye actually takes in. The former is traditionally used for landscape, the latter two for close-ups and portraiture. Most 35mm cameras now have a built in grid overlay to divide the field of vision into two equal horizontal rows of thirds. Based on the rule of thirds or the golden mean, a system dating back to antiquity, I find it worthwhile to use. A lot of artists continue to use the rule of thirds as standard practice, but not all. Before the 20th century, sometime around mid 19th century, the Modern Movement in art completely redefined the visual aesthetic, but then again, relative to art movements, what’s old is new again.

Alison Perry owns a Nyack-based photography business that combines architecture, landscape and formal space and strives to make personal art about time and place. Imagery is for sale through her website. She received BFA in Studio Art from SUNY Purchase and a graduate degree in Library Science from Long Island University. Previously, she worked in journalistic and editorial photography for several different national/regional newspapers in NYC, PA and CA. See examples of her work at alisonperry.photoshelter.com/index

Feature photo shot with Canon 17-40mm F4.0 lens EXP: 1/125 @ F8 ISO 800.

See also:

- Postcard From New York on NyackNewsAndViews

- Walker Evans bio at Britannica.com

- Romanticism defined at Online-Literature.com