I grew up sailing on the Hudson with my father, in a fourteen-foot sloop he built himself. If you launch on the Rockland County side, just North of the Tappan Zee Bridge, there are two distinctive landmarks on the Westchester shore: Sing Sing Prison and the Indian Point Nuclear Power Plant.

For years now, my wife, my daughter and I have had a Father’s Day weekend tradition of attending the music festival that Pete Seeger established in 1966 to help fund the building of the (rather larger) sloop Clearwater, in which Pete participated and which became the focal point of a movement to clean up the river.

As you might imagine, politics, environmentalism, and an anti-nuclear bent with particular focus on Indian Point have always been part of the festival, officially known as Clearwater’s Great Hudson River Revival.

Nuclear power is often closer to a theological’€”rather than a scientific or economic’€”issue: you believe in it or you don’t. And’€”as is true of so much else these days’€”we pick the information that suits the position we start with, rather than working from objective facts to a reasoned conclusion.

So, here’s a little information that I hope will subvert that paradigm.

Whose word do I take about nuclear power?

I accept what the industry says about itself.

What do they say?

That the industry could not possibly survive if it were held economically responsible for the nuclear accidents that will never happen.

This is not the furtive whispering of whistleblowers: this is what they say when they testify before Congress.

An Inconvenient Truth

Going back more than fifty years now, the American nuclear power industry has simultaneously said two, fundamentally contradictory things about the safety of its facilities.

Going back more than fifty years now, the American nuclear power industry has simultaneously said two, fundamentally contradictory things about the safety of its facilities.

Publicly, advocates of nuclear power tell us that nuclear power is safe and that fear of accidents is at best exaggerated, at worst irrational. Only slightly less publicly’€”in testimony before Congress’€”they tell a rather different story.

Under the terms of the Price-Anderson Act, first passed in 1957 and renewed ever since, financial responsibility for the costs of a nuclear accident rest not with industry but with government, at the state and federal levels’€”that is to say, with taxpayers.

As the Nuclear Regulatory Commission notes in its online fact sheet: ‘€œState governments pay 25 percent of the cost of temporary housing for up to 18 months, home repair, temporary mortgage or rental payments and other ‘€˜unmet needs’ of disaster victims; the federal government pays the balance.’€

The accidents that are ‘€œnever going to happen’€ constitute such a basic threat to the financial viability’€”more specifically to the insurability’€”of nuclear reactors, that the industry could not exist without this vast government subsidy and safety net.

Price-Anderson provides an annual subsidy to the nuclear industry worth more than $3 billion and caps the total insurance coverage of the industry at just over $12 billion, while the Nuclear Regulatory Commission’s worst case estimate for the cost of a serious nuclear accident exceeds $300 billion.

Should there be a serious accident, or terrorist attack, at the Indian Point nuclear plant, which is located just north of New York City in a seismically unstable area, the worst case cost estimates (by the Union of Concerned Scientists) for economic damages within a 100 mile zone exceed $1 trillion, and ‘€œcould be as great as $1.2 trillion.

Every Nuke is Above Average

While I don’t sail much on the Hudson anymore, and have lived in central Massachusetts for twenty years now, I still find the citation of 100-mile zones a little chilling: my family lives 100 miles or less from no fewer than five nuclear power plants. One of them, Pilgrim, in Plymouth, Massachusetts (90 miles from my front porch), the design of which is similar to the failed Fukushima Daichi reactor in Japan, was recently the center of a re-licensing fight.

But the Nuclear Regulatory Commission has never refused to re-license a plant. And it didn’t refuse Pilgrim either.

I don’t know anyone over 30 who has never had a car fail inspection.

And I don’t know anyone who has a car that runs on nuclear fuel.

As I write this, the workers in the Pilgrim plant, having gone on strike, have been locked out by management. Nothing to worry about there, either, I’m sure. Plenty of slack in the labor market. I have no doubt that temp workers will do a fine job running the reactor.

Faux Market Capitalism

Nothing new here, of course.

Just a little more Faux Market Capitalism, another industry privatizing the profits and socializing the costs, telling the public we have nothing to worry about, telling the government that the risks of their business are too great for the industry to bear’€”as would be meaningful regulation or oversight.

(Paging Wall Street‘€¦)

Never mind the minor detail that, decades on, we still have no permanent nuclear waste disposal facility, opting instead for ‘€œtemporary’€ onsite storage in aging, spent-fuel pools. If concerns about a nuclear accident in the US are indeed completely without foundation, if reactor operators really have the strength of their convictions behind them, let them lobby for the repeal of the Price-Anderson Act. Let them put up their own money in guarantee, not ours.

Until they do, we would be prudent to heed what they tell Congress, not what they tell the public.

Don Unger teaches in the Program in Writing & Humanistic Studies at MIT. He is the author of Men Can: The Changing Image & Reality of Fatherhood in America, and a collection of short stories, Brokenhearted Ironies.

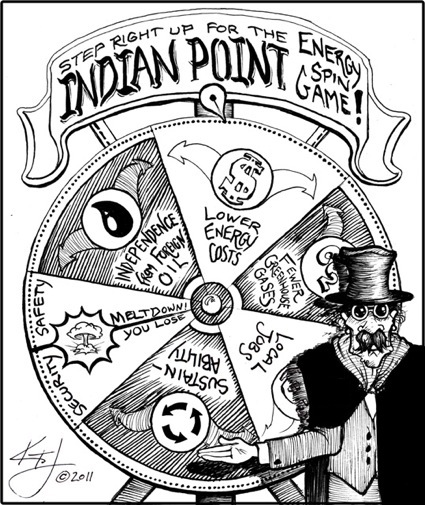

Illustration: ©2011 Kipp Jarden ‘€œIt Takes a Village: Indian Point Roulette‘€ 4/11/2011