In Part I of this two part series, Elijah Reichlin-Melnick looks at the history of the Dark Arts of political redistricting. Part II will examine why it’s hard to draw lines everyone agrees are fair.

“A mother eagle feeding her young. An octopus after crashing through a boat propeller. A baby alien popping out of a stomach.” In response to last week’s release of proposed district lines for the New York State Senate and Assembly, observers were left reaching for whimsical ways to describe the look of absurdly shaped districts that zig-zag crazily across the state with little apparent concern for any consideration other than the political survival of the incumbent legislators who drew them. Andrew Cuomo’s description of the proposed districts was considerably less whimsical’€”the Governor viewed the new lines as ‘€œsimply unacceptable,’€ his spokesman said. While I hope that the Governor follows through and vetoes the proposed lines, there’s no guarantee that he will, given the electoral chaos that could follow (more on that in the second part of this story) so it’s worth examining the absurdities of the current proposal.

Manipulating the redistricting process to frustrate the will of has a long and sordid history going back 200 years. In 1812, Massachusetts Governor Elbridge Gerry is credited (to his discredit) as being the first politician to creatively rework district lines, including a serpentine district that resembled a salamander and led his political opponents to dub the odd shape a ‘€œGerrymander.’€

As most people are aware, the U.S. Constitution mandates that states must draw new boundaries for legislative and Congressional districts every ten years, using data from the most recent U.S. Census. However, the Constitution makes no mention of redistricting state legislatures and gives only minimal guidance on Congressional redistricting, meaning that for most of U.S. history, states were free to do as they pleased when it came to redistricting. Many states simply gave one or two legislators to each county or town, regardless of population numbers. Other states drew districts, but then left them in place for decades, even as tremendous population shifts took place.

In 1962, in the case of Baker v. Carr, the Supreme Court created the modern standard of “one person, one vote,’€ ruling that Tennessee had violated Charles Baker’s right to equal protection. The court ruled that Baker’s Memphis district, which hadn’t been redrawn in over 60 years, and so had ten times the population of some rural districts, therefore rendered his vote worth only one tenth as much as rural voters in Tennessee. This case marked the first time that courts entered seriously into the redistricting process, which had previously been regarded entirely as a “political question” outside the jurisdiction of judges. In the fifty years since Baker, courts have become increasingly involved in key parts of the redistricting process, especially when it comes to ensuring fair representation of minority communities in accordance with the Voting Rights Act of 1965. However, the Supreme Court has repeatedly decided that the U.S. Constitution does not prohibit drawing district lines that benefit one party at the expense of another. So unless a state bans the practice’€”and most states, including New York, do not’€”the political manipulation of district lines is legal.

The failure of courts to invalidate politicized line drawing is understandable as matter of Constitutional law but unfortunate as a matter of policy, since the power to draw district lines is in many ways the power to determine electoral outcomes. Consider the imaginary village of Zyack, home to 80 Democrats and 40 Republicans. In a village-wide election for mayor, the Democratic candidate would be expected to win easily every time, since Democrats have a 2-1 voter registration advantage.

Now imagine that the village board of Zyack is composed of four members, each elected from an equally sized district of 30 people. For the Village Board to fairly reflect the voting preferences of Zyack’s population, a 3-1 Democratic majority would be preferred. However, if Democrats had control of Zyack’s redistricting process, they could dilute Republican influence by splitting the 40 GOP voters evenly, putting 10 into each of the four districts and rounding those districts out with 20 Democrats who would outvote the Republicans every time. The result would be a 4-0 Democratic majority on the village board and Zyack’s Republicans would have no voice in government. If on the other hand, Republicans controlled the line drawing process, they could draw two districts of 20 Republicans and 10 Democrats, and two districts of 30 Democrats and no Republicans; that map would yield an evenly split 2-2 village board, giving Republicans half of the seats even though Democrats have twice as many voters overall.

Back in the real world of Nyack and New York State, the second scenario bears a striking resemblance to the current proposed redistricting plan, which observers have concluded is likely to allow Republicans to keep control of the State Senate in 2012, even as President Obama will likely win New York State with ease.

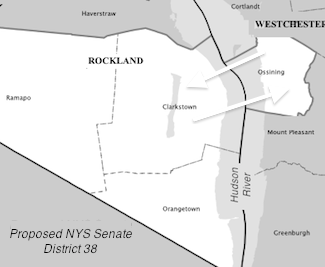

So what’s so bad about the proposed plan? Let’s start in Rockland with a few examples. The 2010 Census pegged Rockland’s population at just over 311,000, close to the ideal size for a State Senate district. And for several decades, the county has been entirely contained within one State Senate district, represented over the years by folks such as Joe Holland, Tom Morahan and David Carlucci. So before last week, you might have guessed that this Senate District would have remained unchanged. But you would have been wrong.

The redistricting proposal announced last week splits Rockland into two separate districts (and Westchester into six!). Haverstraw and Stony Point would be included in a sprawling district that snakes up the west bank of the Hudson past Newburgh and into Ulster County. Orangetown, Clarkstown, and Ramapo would be combined with Ossining, leaving Senator David Carlucci “up a creek without a paddle” with no direct route between two halves of his district on either side of the Hudson. It’s ridiculous — but perfectly legal: connections across water are allowed, even where, as between Ossining and Rockland, no bridge exists.

These examples barely scratch the surface of some of the bizarre proposed districts. Take a look at the maps of the whimsically named districts that started off this article:

- The Mother Eagle Feeding her Young Rochester (Senate District 56)

- The Octopus After Crashing Through a Boat Propeller Queens, NYC (Senate District 15)

- The Baby Alien Popping out of a Stomach Queens, NYC (Senate District 12)

However, simply noting the ridiculous shapes of districts doesn’t do justice to the devious but brilliant methods by which Republicans are poised to use these new districts to lock in their control of the State Senate throughout the next decade. In the second part of this series, I’ll explain in detail exactly how the GOP plan would work to achieve its goals, touch on the similar if milder problems with the Democratic Assembly plan, and theorize about how this mess may all turn out.

In the meantime, take a look at several more of the craziest would-be NYS Senate districts. Perhaps you can come up with your own names for them in comments?

- Queens #16

- Bronx #32

- Westchester #16

- Cortland-Ostego Schoharie #51

- Manhattan #20

- Oneida-Lewis-St. Lawrence-Franklin #47

Elijah Reichlin-Melnick, a Nyack resident, was a candidate for Orangetown Council in last year’s elections. He is the Vice-President of Rockland County Young Democrats, and majored in history and government at Cornell University.