Nyack was one 2,100 communities across America that became all too familiar with the euphemism “Urban Renewal.” In my family, we called the now widely discredited Federal Housing program, Negro Removal.

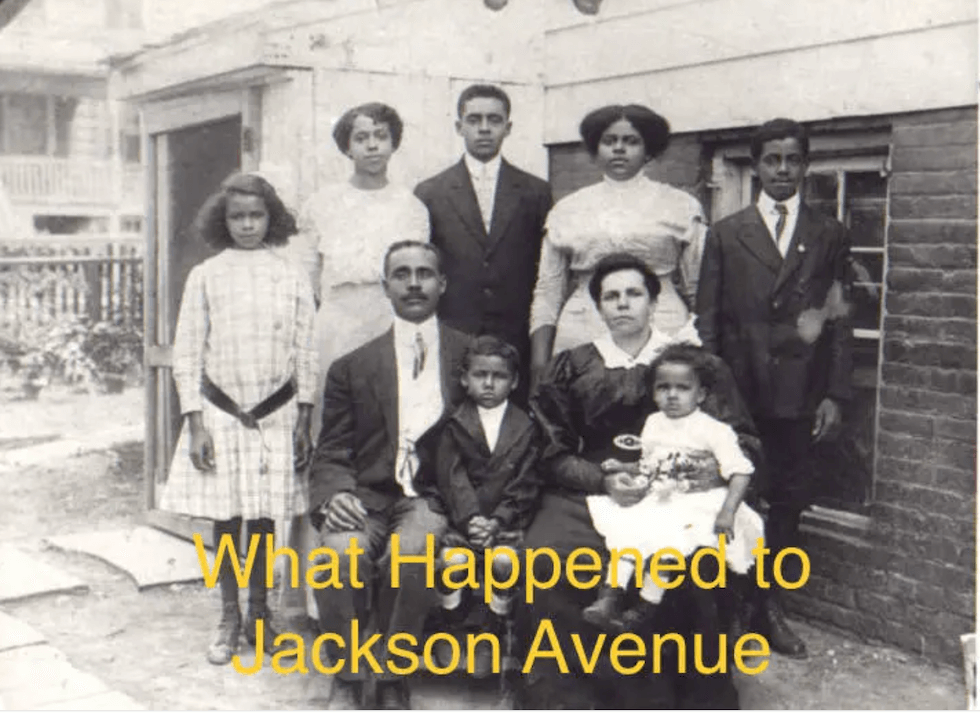

Nyack’s Urban Renewal story is now being told in a documentary titled What Happened to Jackson Avenue. The film had its first public screening on Saturday June 24. There will be another local viewing at the Nyack Center on Friday, July 7, at 8 pm.

So-called “Urban Renewal” projects irrevocably changed the landscape of American cities and villages in the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s. Although the program was proclaimed by supporters to stimulate economic and social “revitalization,” many of these projects resulted in the destruction of entire communities, particularly communities of color. In Nyack, 85 percent of the nearly 125 families displaced in the name of Urban Renewal were Black, even though Black people represented only 18 percent of the population at the time.

Filmmakers Hakima Alem and Rudi Gohl interviewed five Nyackers, each with a personal connection to Nyack’s Urban Renewal program. The interviews form the narrative structure of the documentary, providing first-hand accounts of the demolition of a 17-acre, predominantly-middle-class black neighborhood, bounded by Main, Franklin, Burd and Hudson streets.

Faith Blount describes a vibrant community with small businesses and large nuclear families. The daughter of the founder or Nyack’s Brach of the NAACP and the granddaughter of a successful dry cleaner and tailor, Blount contradicts the notion that the area was a slum that needed to be cleared.

“It was a great neighborhood,” Blount says. “We had a good time, we always felt safe.”

Lonnie “Buster” Leonard remembered how systematically the displacement unfolded.

“Every time someone moved out, their house went down,” Leonard says. “From Burd Street there once was housing, once everyone moved out, it was leveled.”

As if being driven from one’s home and forced to accept pennies on the dollar as compensation was not enough, families like the Leonards were met with hateful, racist recriminations when they resettled.

“My father took his {mortgage} application to the bank.” Leonard says. “The person put in the trash right in front of him…By the grace of God and a couple of lawyers and some political friends, we got a house on High Avenue.”

My grandmother, Frances Lillian Avery Batson, was also able to purchase a home in Nyack with the settlement provided through the process of eminent domain.

According to the documentary, eminent domain is defined as “a legal process that permits the government to take possession of privately owned real estate in the name of the greater good. It is most commonly used for roads, railroads and public access. In Nyack, properties were demolished because they were considered decaying or unsightly as well, particularly in areas deemed central to the fiscal health and vitality of a community.”

My family and the Leonards were more fortunate than most of those forced from the area. The Blount family was also able to buy a house in Orangeburg. Barbara Williams, who moved to Nyack from Anniston, Alabama recalled that many of the homeowners from the demolished area who were displaced were “reduced to being renters the rest of their lives.”

Many others had their dreams of owning dashed by racism in the real estate market. According to remarks my grandmother made at a Nyack Civic Association during the demolitions:

“People who have homes to sell in various parts of the county and township are not willing to open their hearts and minds. What are people going to do? Build a few tents on the hill and go back to nomadic life? Rockland County is prejudiced. That’s got to be considered. The present conditions would have not existed if a few people had been ready to open the properties.”

The timing of the documentary is particularly compelling because of an affordability crisis in Nyack that is having a similar impact on renters in the village as Urban Renewal did several decades ago.

The American dream of homeownership also eludes tenants in Nyack Plaza, a development that was built on the Urban Renewal footprint, even though some rents are approaching the level of a mortgage payment.

Nicole Hines, president of the Nyack NAACP, said she hopes the documentary sheds light on ongoing challenges for the community and sparks movement in addressing those challenges.

“Fair housing and home ownership continue to be key issues for the NAACP and for everyone we represent,” Hines said. “We hope this film will advance the discussion and motivate change.”

The auditorium in Nyack Center was deafeningly quiet during the screening as people were exposed to an epic injustice that occurred under the ground that they walk every day.

What Happened to Jackson Avenue was produced by the Phoenix Ensemble Theatre, as part of their inaugural Phoenix Festival in Nyack in 2022, that included world-class theatre, music, dance, and one-of-a-kind performances. In an effort to create programming that would engage the history of the village, they discovered that a parking lot where they had stopped for a conversation was once a community that was destroyed, leaving a wound that has yet to heal. The documentary was born from that discussion.

Other communities still scarred by the impact of Urban Renewal programs have begun to address the injustices and loss of generational wealth.

In Palm Springs, California, Black and Latinae families are seeking $2.3 billion in compensation for the destruction of a square-mile area known as Section 14. In November 2021, the Hayward City Council in California passed a resolution to formally apologize for destruction of Russell City, an unincorporated area of Alameda County that was largely made up of African American, Latinae and other People of Color.

In Nyack, the Batson family house that was assessed at $13,730.00 during the Urban Renewal process would now be worth $457,065.28. The estimated total loss of generational wealth from those displaced by Nyack Urban Renewal could be as much as $30 to 40 million.

What Happened to Jackson Avenue will be screened again on Friday, July 7 at 8:00pm at Nyack Center and presented in collaboration with Rivertown Film. A panel discussion will follow the film.

Tickets are available here: Tickets.

An activist, artist and writer, Bill Batson lives in Nyack, NY. Nyack Sketch Log: “Urban Renewal Haunts Nyack” © 2023 Bill Batson. Visit billbatsonarts.com to see more.